Abandoned

A look at what happened to a rural elementary school that was closed and left behind

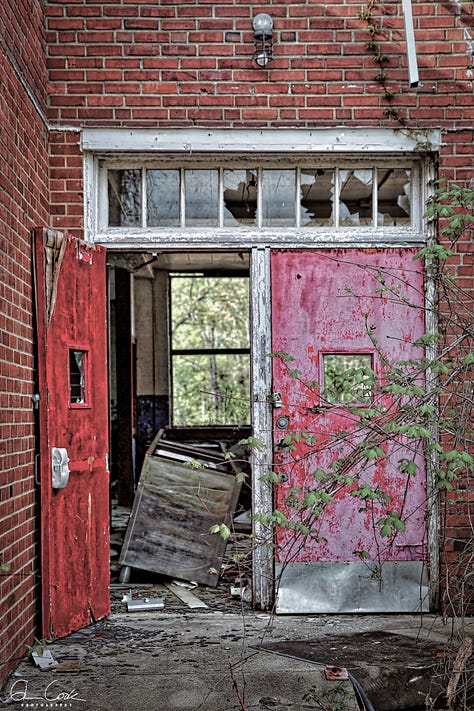

Just off a state highway in rural North Carolina, a school that educated elementary-age children for almost 70 years sits vacant and crumbling more than two decades after its doors were closed to students for the last time.

In December 2003, Monroeton School students moved to a new building down the road on U.S. 158 that had been in the works since funds became available to Rockingham County, N.C., seven years earlier. Soon after, the property was surplus, but the main building and grounds have not been occupied since the schoolchildren left.

While many closed facilities are adapted and reused, either by private groups or public entities, countless school buildings have been left abandoned across the United States. The cost to renovate these facilities and bring them up to current building standards is often too high, so they are either demolished or left to slowly disintegrate.

Aging trailers and an outbuilding added when enrollment grew past the school’s original seven classrooms crumbled. Over time, vandals broke the windows, toppled the last remaining furniture, and lined the walls of the former gymnasium and halls with graffiti. In 2013, three men from a neighboring county were arrested for stealing copper and metal from the building, the only salvageable scraps with quick resale value.

I saw the damage and the decay while taking these pictures in 2015. The Facebook post that followed resulted in hundreds of nostalgic comments about the school and the memories that going there brought. But the feeling that something had been lost was outweighed by the reality; the building was a shell of itself, a throwback to a simpler time that no longer existed.

This story is not unique. If anything, with aging buildings and enrollment on a steady and increasingly steep decline nationwide, school districts are facing tough decisions about whether to close facilities that no longer have enough students or are simply not making the grade.

1930s WPA project

The old Monroeton building, which opened in 1936, was the product of the New Deal-era Works Progress Administration (WPA). Located in an unincorporated portion of Rockingham County, a tobacco and textile region that borders Virginia, it was one of several schools built during a massive expansion program that began three years earlier when the General Assembly voted to take over school funding in an effort to standardize education opportunities for students.

Numerous buildings in the county and its incorporated towns — Reidsville, Eden, Madison, and Mayodan — were built during that era as the state moved away from the traditional one-room schoolhouses. In 1931, North Carolina passed a law cutting teacher pay in schools with less than 22 students, forcing counties to look at consolidation.

By decade’s end, the state transported more children to school by bus than any other, according to a report published in 2010 by the North Carolina Museum of History, while keeping its average per-student cost at just over $5, easily the lowest in the nation.

Ironically, more than a half century later, it was consolidation of a different sort that led to the closing of Monroeton and other schools built during that era.

In 1993, Rockingham’s four districts — Reidsville, Eden, Western Rockingham, and the county — consolidated into a single school system. The move, driven largely by Reidsville, was controversial because each district had its separate identity and method of operations.

One prime difference was how schools in the districts were configured. Reidsville operated on a grade K-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-12 model. Eden, which consolidated three small districts (Leaksville, Spray, and Draper) when it incorporated in 1967, used the more common K-5, 6-8, 9-12 model that you see today. Western Rockingham used a combination of grade configurations for the three communities it served, while the county system did as well.

In 1996, district leaders proposed a move to the K-5, 6-8, 9-12 model as part of a long-range facilities plan that focused primarily on building a new middle school and three elementary schools in the former county system, plus one to replace an aging school in Reidsville. Using bond money, the project finally got underway two years later.

The Importance of Infrastructure

School facilities long been an interest of mine, personally and professionally. As the child of two teachers, I saw the challenges they faced working in aging, subpar buildings. In 1991, while the city editor at my local newspaper, I wrote all the copy for a six-page special broadsheet report that focused on our district’s declining facilities; the section was credited with the passage of a huge referendum that led to the demolition and rebuilding of several schools.

Over the years, I’ve continued to write about the need to improve school infrastructure, especially as research has shown that quality school buildings result in better academic outcomes and attendance rates as well as improved safety and security. That runs counter to the public’s investment in school facilities; the average age of a main instructional school building in the United States is 49 years, with almost 40 percent opening prior to 1970, according to a December 2023 survey by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Major renovations or additions have occurred in roughly half of the schools that were surveyed, but the average age of the renovation was 13 years.

Since COVID, districts across the nation have used federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds for facilities improvements, largely to address issues around heating, ventilation, and air conditioning problems. According to the NCES survey, 21 percent of all schools were undergoing such efforts in December 2023.

The infusion of federal dollars, while good for local districts, only touches on part of the problem, says Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, a national nonprofit that advocates for K-12 infrastructure improvements. A 2021 report by Filardo’s organization estimates that school infrastructure investments nationwide are $85 billion less than they should be annually, and that gap is continuing to grow.

“Funding for school infrastructure is very local, which means it’s the most inequitable,” Filardo told me for a story published in American School Board Journal this July. “If you don’t have the resources to improve your buildings, which happens frequently in communities that have significant lower-income populations, and you don’t have help from the state or the federal government, then you’re in a constant struggle that benefits no one.”

Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean for public health practice and community engagement at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says students in Maryland’s Baltimore City Schools lost about 1.5 million hours — the equivalent of 221,000 days — in the five years prior to the pandemic due to the physical condition of the buildings. In communities like Baltimore, where 80% of students come from low-income homes, lost instructional time directly affects learning and achievement.

“The condition of our school buildings reflects years of disinvestment, and this cumulative underfunding makes it very hard to just fix the problem in a way you can fix operating funds from one year to the next,” Sharfstein says. “Fixing something of this magnitude is a whole other order. I feel like I’m staring in the face of history when I look at these buildings.”

I understood what Sharstein was saying, having stared into the face of history almost 30 years before.

The End of Monroeton

In October 1996, the month before the Rockingham County bond referendum, I was hired as the district’s public information officer. One of my first tasks was touring the county’s 25 schools with the superintendent, who discussed the variety of challenges each school faced.

Walking into the former county schools was a step back in time. The two largest (Bethany and Wentworth) were former K-12 campuses that had become K-8’s when the system’s high school — and most recent new building — opened in 1978. Both Bethany and Wentworth had opened in the 1920s.

On the opposite end of the county, two small K-4 WPA-era schools (Happy Home and Sadler with less than 400 students between them fed into a grades 5-8 school (Lincoln). The latter school had been the K-12 campus for African-American children prior to integration.

Monroeton, which served grades K-6, was something of an anomaly, even in the old, predominantly white county system. Just 5 to 7 percent of its population was minority, even though it was the county school closest to Reidsville, where the students were split 50-50 black/white. Despite having the highest achievement in the district, Monroeton did not have the same strong community identity as Bethany or Wentworth because its students left after sixth grade; middle schoolers went to Bethany for grades 7-8.

Over the years, Monroeton had greatly outgrown its original building, with the number of portable classrooms exceeding those in the main facility, despite underutilized schools just seven miles away in Reidsville. In 1995, a redistricting plan failed amid a huge uproar just after consolidation, so the building program was seen as a way to nudge residents in that direction.

That generally has occurred, though not without its share of bumps and controversy. The Bethany community fought fervently to keep its middle school and opened the county’s first and only charter to serve grades 6-8 in 2000. In 2017, the charter school eventually left the nearly 100-year-old campus and moved into a new building, expanding its focus to grades 6-12.

Like many rural regions that have lost their once-strong industrial base, Rockingham County has dealt with declines in population and, as a result, in student enrollment. The district has lost 3,800 of the 14,500 students it had in 2000.

In October 2004, three years after I left the school district, the Monroeton building and its surrounding 10 acres were declared as surplus property. The board set an asking price of $100,000 for the site and the land was eventually taken off the district’s tax rolls, but nothing else was ever done, leaving the building to slowly crumble.

I went here in fourth grade. My teachers were Mrs. Knight and Mrs. Costanoro. One of the best years, went to the jaw river for a three day field trip.

I went to this school 1st and 2nd grade as did my older sister who attended 1st grade through 6th grade there . my 1st grade teacher Mrs Justice tought my dad and my uncle . before I was ever thought of 😃