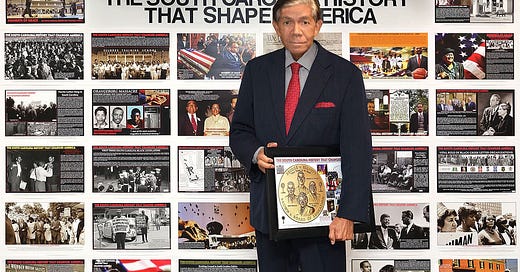

Conversations: Cecil Williams

Civil rights photographer, South Carolina historian talks about Briggs v. Elliott

Cecil Williams was just 9 years old when he received a “little magic box” that changed his life.

That box — a $2.50 Kodak Baby Brownie camera from Sears & Roebuck — helped Williams become a “living witness to history” as he chronicled the Civil Rights Movement in South Carolina.

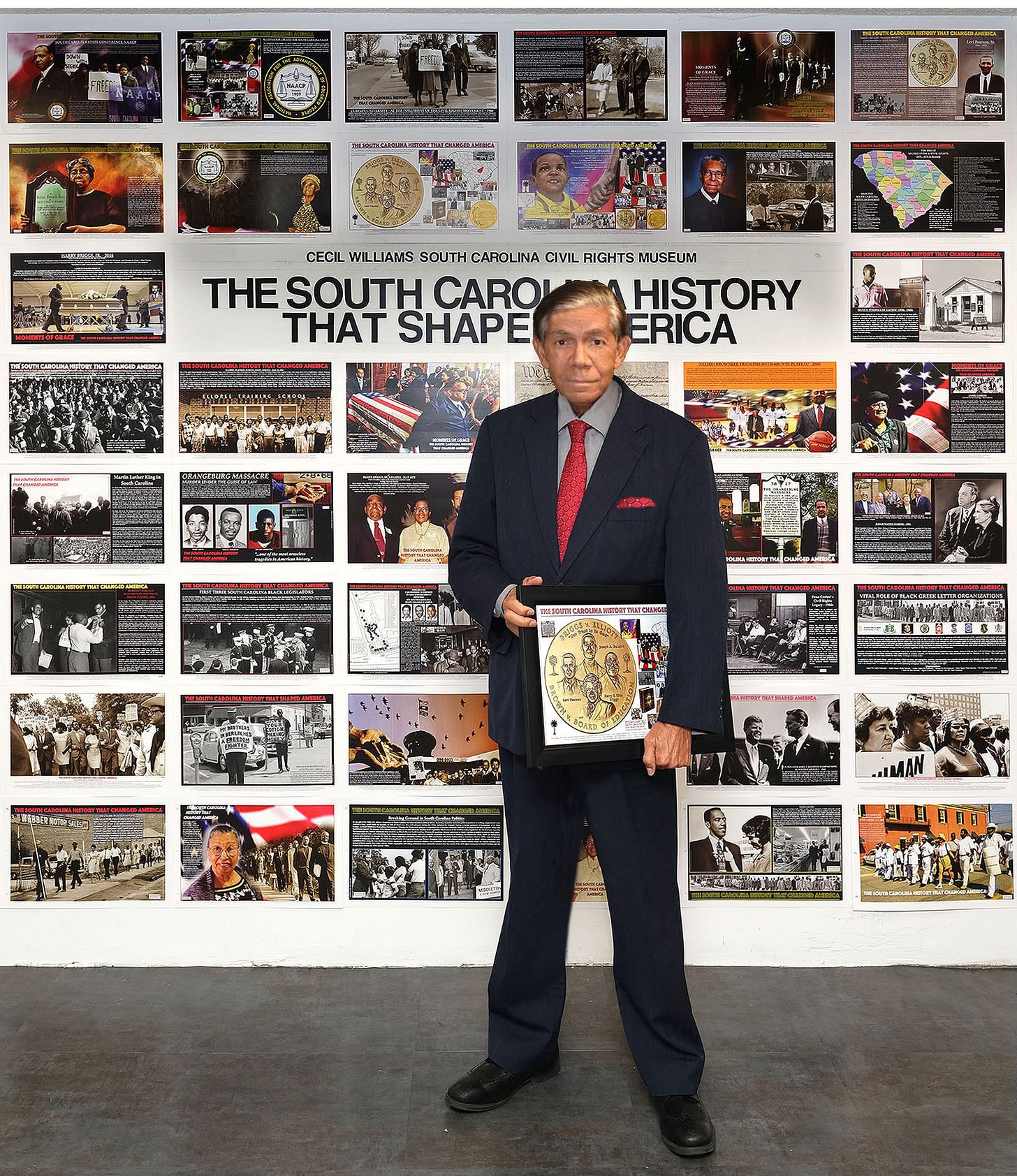

Still active and feisty at 86, the Orangeburg, S.C., native does not want that history to be ignored or lost as the 70th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education approaches. In a 3,600-square-foot Orangeburg house that he designed, Williams has opened a museum devoted to the state’s role in the Civil Rights Movement; the museum is the first of its kind in the South Carolina.

“South Carolina is one of the only states in the Deep South that did not have a civil rights museum. The state has wanted to hide this history,” Williams told me in an interview last year. “Most of the history books do not recall the role this state played in the movement, and we need to correct that narrative, amplifying stories that have been marginalized.”

By age 15, already armed with a driver’s license and freelancing for Jet magazine, Williams had photographed many of the events and families associated with Briggs v. Elliott, the first of the five lawsuits that led to the Supreme Court’s 1954 desegregation ruling. Orangeburg is located about 40 miles southwest of Summerton, the Clarendon County town where the Briggs case originated.

Williams went on to photograph every major civil rights event in the state, from Harvey Gantt’s arrival at Clemson University in 1963 to the Charleston hospital workers strike at the end of the decade. He was there with his camera when the Confederate flag was removed from the state capital in 2015 and has photographed every president — with one notable exception — since John F. Kennedy.

Working with Nathaniel Briggs, the son of the original plaintiffs, Williams is trying to get the U.S. Supreme Court to rename the Brown decision in its official records. (A petition was filed with the court in November 2023 by Camden, S.C., attorney Thomas Millikin.) The reason they’re seeking the name change: Briggs was the first of the five lawsuits filed — a full year before Brown — and Thurgood Marshall developed his legal argument for desegregation while working on the South Carolina case.

“We are very realistic about what they might do with it,” Williams said. “They can choose not even to hear it. They can choose not even to acknowledge it. The thing is, if America is to really reconcile with its history, this is one of the untruths that must be resolved at some point.”

(Note: After this interview was published, the court declined without comment to discuss the name change.)

Over the course of 45 minutes, Williams and I talked about Briggs, his encounters with Marshall and Kennedy, and of course, photography. The conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How did you get involved at such a young age with the Briggs case?

Williams: When I was 12 or 13, an attorney here in Orangeburg took me to Charleston to see Thurgood Marshall arriving on the train. I had moved from my little Kodak Brownie to another camera that had a flash on it. I took one photograph of him getting off the train because the flashbulbs cost $1, and they used it in Jet magazine.

We were going to stay for the trial (in federal district court), but there were too many people wanting to get in. Waiting outside is how I came to know about the Briggs petitioners. I also got to know the Rev. J.A. DeLaine (an educator and pastor in Clarendon County who became the catalyst for the Briggs case) through my mother, who had taught with him in Calhoun County for a brief time.

When I was 14 and 15, my mentor was E.C. Jones, who owned Majestic Studios in Sumter and was also the photographer for the South Carolina State College yearbook. When he didn't want to drive all the away from Sumter to Summerton to take pictures on the Briggs case, I would drive down and take them for him. So, from three different perspectives, at a very early age, I was drawn into it.

Over the years, there’s been speculation about the reasons the case was named Brown and not Briggs. The most prominent is geography; some say it was more politically palatable to have the decision named after a case that started in the middle of the country (Brown is based Topeka, Kan.) rather than in the Deep South.

Williams: I’ve heard that. I read a few reports where Robert Carter (who served under Marshall at the NAACP and succeeded him as the organization’s lead general counsel) said, "Well, Thurgood, maybe this might be a blessing in disguise that it will be not a Southern-based decision that is the lead case." And because (Marshall) worked down here for so long and saw what we saw, I think he believed that was true.

One of your photographs, of the DeLaine family looking at their home that had been burned to the ground by segregationists, is chilling and powerful. So many of the petitioners faced retribution for their involvement in Briggs.

Williams: Thank you. Many of the families left Clarendon County and dispersed to all parts of the United States after they filed this case. They couldn’t find work to survive in South Carolina, and the Rev. DeLaine was forced to leave because things were so bad. He was under so much pressure and so many threats.

In 1955, as a senior in high school, you rode in a car with Marshall and photographed him when he made a post-Brown tour of the state. What was that like?

Williams: You can imagine how exhilarating it was for me as a young boy to be riding around in the car as Thurgood Marshall visited all the people in the community. He came to Columbia, Charleston, Orangeburg, and Clarendon County, and I photographed him at Claflin University (in Orangeburg). It was unforgettable to be in the midst of such a great person.

I was sitting in the back seat with him. His long sprawling arm was across the back of the seat and I sat there with my big old Crown Graphic Camera. Every other word out of his mouth was cursing and profanity. That’s what I remember, him being so confused and upset and frustrated that America was not ready to accept freedom, justice, and equality for everyone. After that, he didn’t come back to South Carolina; he started going to Topeka instead.

For the longest time, there’s been a stubborn resistance — if not outright refusal — to recognize the role that Briggs and South Carolina played in the Civil Rights Movement. Much of that has come from residents in your state.

Your 2006 book, Out of the Box in Dixie, tried to rectify that by focusing on the Briggs case and the Orangeburg selective buying campaign in 1963 that boycotted white businesses. Did you feel that same resistance to your work?

Williams: Oh yes. Briggs has always been the footnote in history, and this is so unfortunate. When my book came out, I was getting requests to do exhibits and also book signings at various places. In Atlanta, the High Museum of Art scheduled me to do an exhibit and signing there. Now mind you, my book was 300 pages of history, and Martin Luther King Jr.’s name was not even mentioned. After they got the book, they cancelled the exhibition and signing because I had the audacity to leave out what most people think is the person who started this movement.

It wasn’t that I was trying to diminish all the greatness that Dr. King, of course, achieved, but that I had the audacity to leave him out of the book entirely, even though most of what he did was in other states.

My thought on the book was that all this history had taken place in South Carolina, but many people in Clarendon County maybe did not have the educational background to tell their stories. They didn’t need me to write about Martin Luther King. People needed to know that Briggs was first.

I've always found it fascinating that nothing seemed to change in Summerton for decades. From what I observed, the whites in the town just shrugged and refused to acknowledge what had happened there.

Williams: They did, but most African Americans are confused about it too. Most of the original petitioners themselves have died and today people don’t understand that Clarendon County was at the forefront of starting the Civil Rights Movement. They don’t know that their place in history was hijacked.

Now the history books, the Internet, everyone just thinks of it as one case: Brown v. Board of Education. People think Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King were the ones who started the Civil Rights Movement. Society likes to keep our history simple and clean, but it’s not simple and clean. I’m a living witness to that history.

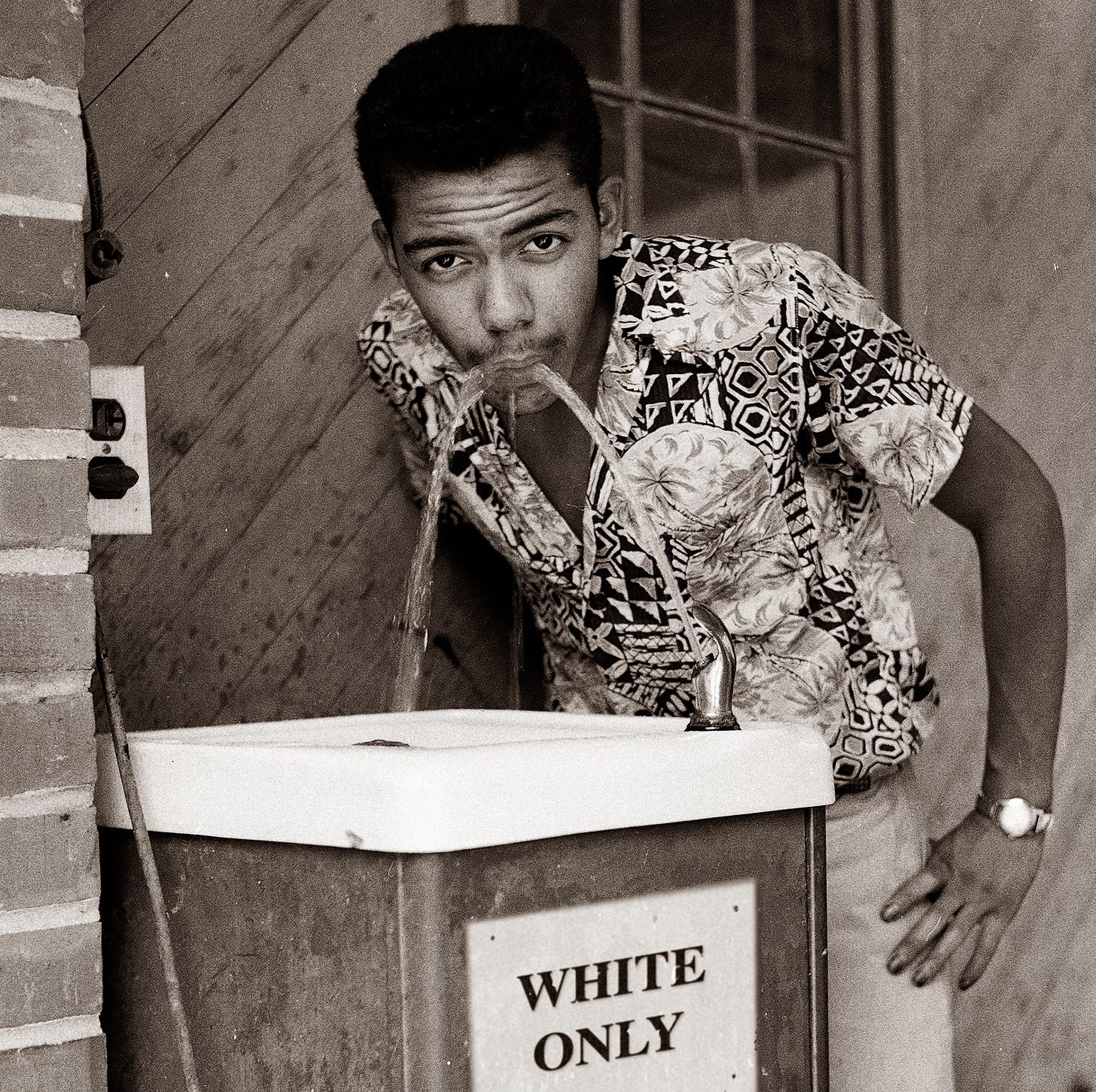

Your photography is just gorgeous. In your black and white work, the tone and contrast is really superb.

Williams: Well, thank you. I tried to put dignity into the people doing things in that time. In Out-of-the-Box in Dixie, every picture was tweaked to make sure the people are accurately represented, especially those with various degrees of the colors of the rainbow. African-Americans sometimes appear in darker complexions than they really are with black and white photographs, especially if they're wearing a white shirt. In every picture, In every picture, I try to render the skin tones more faithfully and pay close attention to the density and the levels and the dynamics of a photograph.

You’ve had a fascinating career.

I’ve been fortunate to have some things fall into my lap, like the attorney taking me to photograph Thurgood Marshall. And I’ve managed to be in the right place at the right times. I’ve also been willing to go all over the state to get good pictures, and that’s worked out well for me.

I have photographed every president since John F. Kennedy, except, of course, Trump. I would never photograph Trump.

I saw a video of your Kennedy story at the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas. Can you tell me more about your encounters with him? (Background: In January 1960, Williams, then a senior at Claflin University, was visiting relatives in New York City and went to capture images of Kennedy at a press conference. He had forgotten his press pass, and as Kennedy came to the podium, hotel security was trying to make him leave.)

Williams: He saw what was happening and stopped the guards. I identified myself as a photographer for Jet magazine and he said of course I could stay, so I did. Afterward, he reached into his wallet, pulled out his business card with his personal number and address, and told me to contact him.

Over a three-month period, I photographed Senator Kennedy campaigning several times. I actually flew in his 10-seater airplane, the Caroline, which was named after his daughter. We went from Columbia to Atlanta and back to Columbia. When people see the picture I have of him coming off of his airplane, they think it’s Air Force One, but it’s actually his Caroline airplane.

Do you still take pictures?

Williams: Of course. I have a studio here at my museum, but it has taken the back seat since nowadays everybody is a photographer. I can't make a living out of it anymore. The thing I do mostly today is restore old pictures. Anytime we get hold of pictures of the Briggs family, the DeLaine family, or the Pearson family (another of the plaintiffs from Clarendon County), they're all cracked up or broken or faded in a way. We restore them and bring them back to life because this is a history that has to be restored.

Film or digital?

Williams: I use digital, of course. I was an early adopter. Many of my fellow photographers did not, but I embraced digital as soon as it came out and as soon as the cameras were under $5,000. In the early days, though, whenever I would do a wedding with digital, I would always also carry a film camera with some rolled film just in case. I never needed it, but I carried it.

After all this time, what still fascinates you about photography?

Williams: The fact that I’m involved in using one of the greatest educational tools there is. Photography is very powerful. It’s a tool that we can use to teach our youth and make an impact on their young minds. With these images, we can show you heroes. Not Spiderman or Superman, but real heroes who pushed for freedom, justice, and equality. These are the heroes who should be recognized and honored.