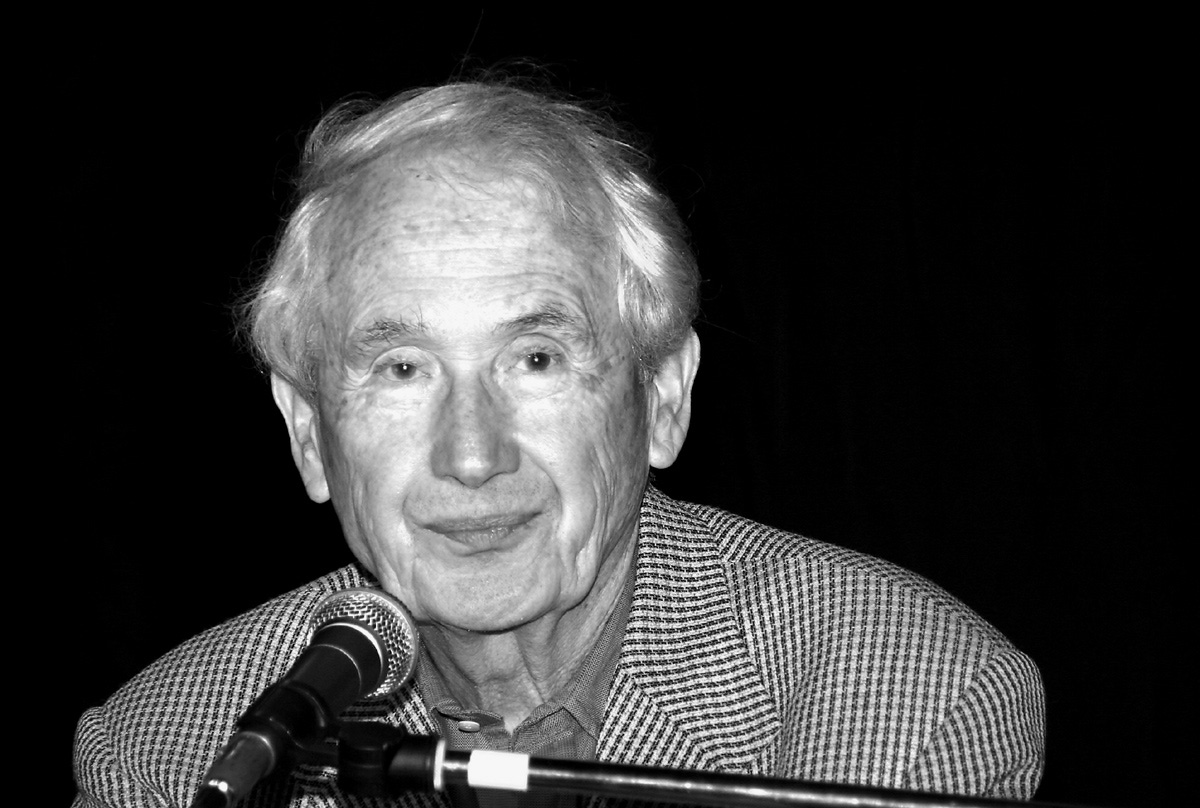

Conversations: Frank McCourt

In 2005 interview, 'Angela's Ashes' author talks about his 30-year teaching career

Frank McCourt was best known for Angela’s Ashes, his Pulitzer Prize-winning tragicomic memoir of growing up in Limerick, Ireland. But he held off on writing the book, as well as two subsequent memoirs, until he retired from a 30-year teaching career in New York City’s public schools.

Angela’s Ashes, published in 1997, was a rarity: A literary and commercial sensation. That was due to McCourt’s vivid descriptions of his childhood with an alcoholic father who abandoned his family and a mother forced to beg on the streets to keep her four children fed and clothed.

“When I look back on my childhood, I wonder how I survived it at all,” McCourt wrote at the start of the book. “It was, of course, a miserable childhood: The happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood.

The book ends with the 19-year-old McCourt, who had dropped out of school at 13, on a ship bound for New York and a new life, which he covered in his second memoir, ‘Tis.

His start in America was not smooth sailing, at least initially. After a series of jobs, he was drafted into the Army during the Korean War. But once he was discharged, McCourt was admitted to New York University despite his lack of formal education. In 1957, he earned a degree in English and started teaching at McKee Vocational High School in Staten Island. A decade later, after earning a master’s from Brooklyn College, he moved to the elite Stuyvesant High School, where he remained until his retirement.

McCourt covered his teaching career in his third and final book, published in 2005. Soon after Teacher Man came out, I interviewed him for American School Board Journal.

After two successful memoirs, why write a third book?

You retire from teaching and you have time for reflection. When I look back on 30 years, one of the things that emerges is the reputation and status of teachers in this country. We have a patronizing attitude toward teachers. People think of it as the profession of failures. We have respect for movie stars and football players and CEOs, but the teacher doesn’t get respect. I find that appalling.

I don’t understand why there is such hostility. The public doesn’t know what the teacher does in the classroom, what sorts of varied roles you have. I certainly didn’t know it when I went into the classroom, and I certainly had to fumble around until I learned what I was doing.

Why did you go into teaching?

When I got out of the Army, I had the G.I. Bill. I had no high school education, but NYU took a chance on me and let me in. I suppose I was what you might call a mature student of 22. At one time I thought I'd like to become a journalist, but because I had no education and no self-esteem, I didn't see myself doing that.

With teaching, I thought the students would all sit there and I would be their hero. Well, it didn't turn out like that. I wanted to become a teacher because I had a misconception about it. I didn't know that I'd be going into into a battle zone. No one prepared me for that. I had to be on my toes all the time.

How long did it take you to become a good teacher?

It took years. It's like writing I suppose, or like any art, or any human endeavor. Eventually you have to find your own way.

Sometimes I would imitate other teachers who had certain ways of dealing with classes. It didn't work; it never worked. The same thing applies to writers. You imitate Faulkner, you imitate Fitzgerald, you imitate Hemingway, but in the end you find your own voice and your own style. That’s what I had to do as a teacher.

You didn’t write Angela’s Ashes until you were 66, and in Teacher Man, you say that you didn’t read much because you were so busy grading your students’ work. What did you learn from reading their work?

With the kids, I had to be teacher and critic. I had to help them start sorting out the different styles of writing. More and more, I started preaching clarity, clarity clarity, simplicity, simplicity, simplicity. Over time, I think I learned to achieve that myself.

When I was younger, my own writing tended to be derivative and literary. I tried to be clever; I tried to be Evelyn Waugh. I didn’t know you had to find your own style and your own voice. I’m a late bloomer, and I’m a late learner. It’s hopeless.

What are your thoughts on standardized testing and how it affects teaching?

Some take refuge in the subject matter, something called the textbook. This is the chapter we’re going to read. This is the chapter we’re going to study. That’s not education. That’s conditioning. For some that’s satisfying because they stick to the subject, but kids always want to know why you are teaching this or that. That’s an opportunity to engage them, and we don’t take enough time to engage our kids because we’re always preparing them to take a test.

Politics are everywhere in schools today. What do you think about the standardized test movement?

Here’s where I get on my soapbox. So much of the problems we have today in schools start with politicians who somehow badger their way into education. They control the purse strings — it’s really the only power they have — but they use it to show that they are the experts. This is a monumental show of disrespect.

I don’t think we should prepare students to be ants in the commercial marketplace. There should be clear areas where we stop and ask ourselves, “What are we doing here? What is this all about?” But no, we get on an assembly line and stick labels on kids.

It has nothing to do with learning. Or should I say it has nothing to do with wisdom, which we are supposed to be in pursuit of.

If you could put together the perfect staff at a school, what would you do?

If you had a wise and benevolent administration with a principal who taught for long time, and supervisors and mentors with a huge collegiate sense of responsibility, then I believe you would have a warm and vibrant school. It’s a community rather than a series of tribes with teachers down at the bottom. We have to elevate teachers.

After McCourt’s death in July 2009, New York City named a school in his honor. The Frank McCourt High School is located at 145 West 84th Street in Manhattan.

Another wonderful interview, Glenn. The questions posed to McCourt elicited clear, rather simple responses that echo my own experience. I wonder what he would say if he were currently in the classroom.

Teacher of 26 years as of June 2023.The workload has increased so much in the last 12 or so years. Local schools do not have decision making rights. We are given our curriculum and trust me there is none of the politicization topics the media says we are teaching. I love my career but I do not love the testing, the disrespect, the workload. I work for pennies per hour. I know I should not work at home but my kids(students) get one day in school at a time. There are no repeats. They deserve quality lessons, timely feedback on assignments and a teacher to meet their needs(academic, physical and yes social/emotional). Time is of the essence but my planning time is swallowed by meetings, data collection(that needs to be gathered but never examined). So I work on my time because my kids do not get do overs.