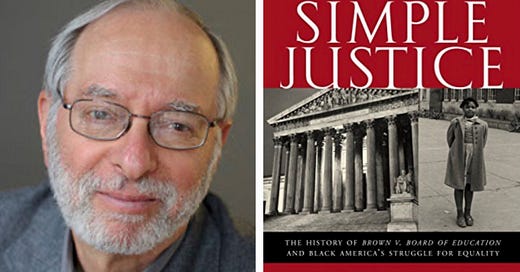

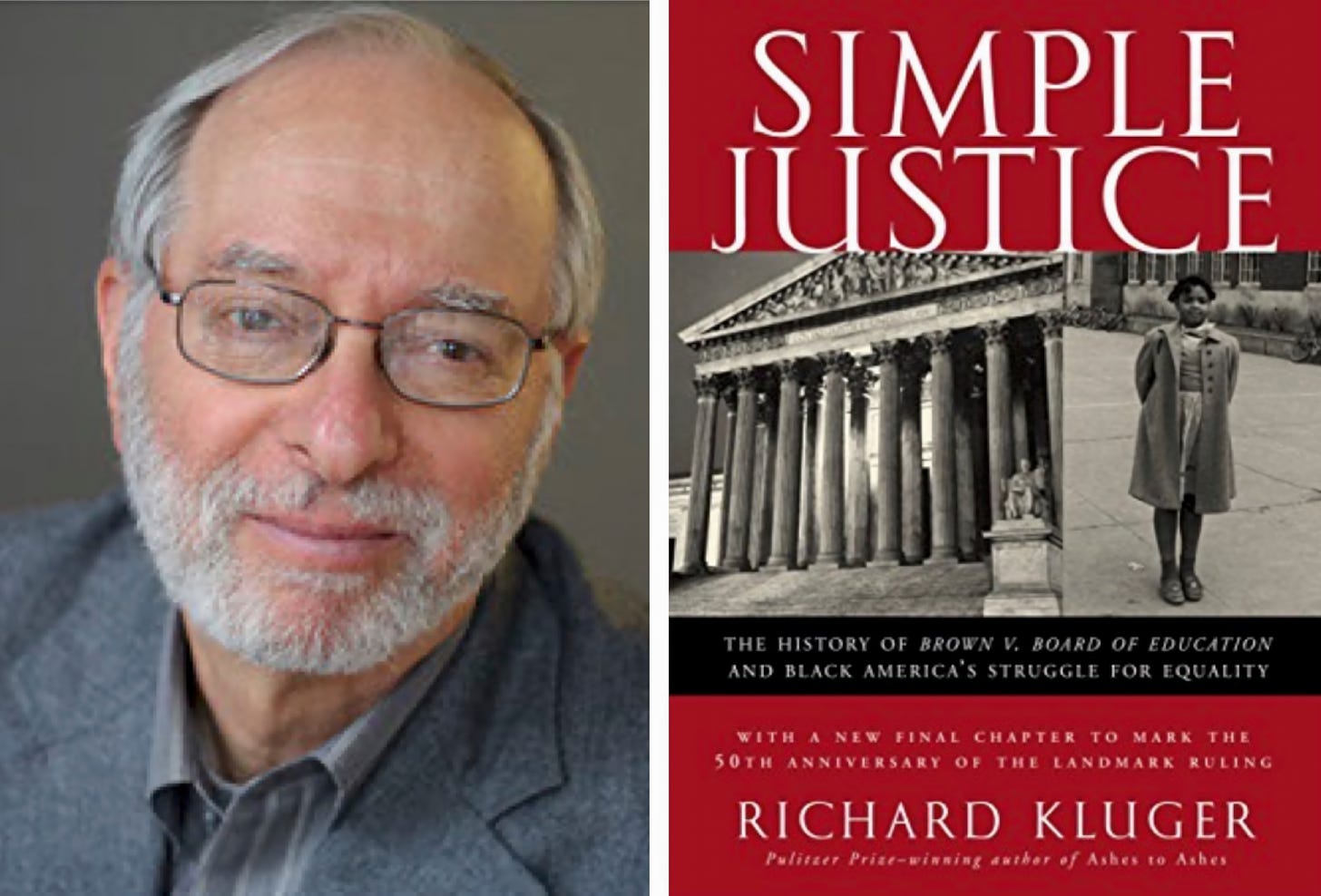

Conversations: Richard Kluger

Pulitzer Prize winning author discusses comprehensive history of Brown v. Board

It took a “blaze of hubris” for Richard Kluger to spend six years of his life researching and writing Simple Justice, a massive 883-page book on the history of Brown v. Board of Education. At the time, he was a former journalist who had published two novels and was working as an executive editor at Simon & Schuster.

But in 1968, a year of tremendous upheaval in the United States that included race riots in major cities following the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, Kluger decided to take on the project.

“As a white guy living in New York with a family, I was not much involved in anything,” Kluger said told me during a 2004 interview as the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board approached. “I wasn’t on the barricades. But it seemed to me this might be a way to really participate in what was going on in the country.”

Kluger admits he tried to get others to write Simple Justice before he took on the project. “I was not a novice writer, but I had never done a nonfiction book,” he said. “I tried to get other people to write it. I approached journalists, but they didn’t have the legal background. I went to scholars, but they didn’t want to have to do the legwork. In a blaze of hubris, I decided I was going to do this.”

But the hubris and hard work paid off. Simple Justice has not been out of print since it was first published in 1976. It launched Kluger, now 89 and living in New Jersey, into a nonfiction career that included The Paper, a history of the New York Herald Tribune that also was a National Book Award finalist. In 1997, he won the Pulitzer Prize for for Ashes to Ashes, a historical study on the American cigarette industry.

Here are more excerpts from our conversation:

Most scholars and researchers call Simple Justice the seminal work on Brown — partly for the stories of the people involved.

One reason book is so huge is that, when I was not quite halfway through the research, I saw that each of the five cases had really moving narratives and the people were real people. Any one of them could have been the whole book. I went to my editor at Knopf and said this was going to be an immense book if I tried to render the people as well as the social content. He said, “Do it right.”

What is the legacy of Brown? Did the decision accomplish what the Supreme Court and the plaintiffs hoped?

It’s easy to say the glass is half full and half empty. I think it’s a little more than half full, but it’s not brimming. There have been two generations since the decision. By historical standards, that’s not a long time to expect a major social inequity to be corrected, especially one that lasted a dozen generations. That’s an unrealistic expectation.

On the one hand, anyone who expected things to be transformed in 50 years — especially given the immensity and enormity of degradation against blacks — is dreaming. And yet so much has happened on the plus side in that time. Black America is no longer a subculture; as a whole, it has been integrated into mainstream American culture. Black America affects everything we do today.

Blacks have made tremendous strides in so many ways. Let me share with you only two statistics. In 1950, 14 percent of all blacks were high school graduates. In 2000, 77 percent were high school graduates based on the census. In 1960, there were 55 percent of blacks living at or below the poverty line. Today, it’s 22 percent. That’s still a big number. It’s still twice the number of whites. But it’s an immense change.

The downside on Brown is that we’re still a long way from social equity and integration. Resegregation is fact. It’s political. It’s the Supreme Court through its decisions since [Chief Justice William] Rehnquist came onto the court in the ‘70s. We haven’t really done a lot of desegregating as a nation. The South has probably done a better job than the rest of the country, but it had more to make up for than anybody.

How did you come up with the book’s name?

The title was not an idle gesture, even though some people might think so. There’s irony in the title of the book. The decision seemed so inarguably correct and right, but there was so much confusion, anger, and hatred at that time.

Where, in your view, do race relations stand now?

I think the schism in the Black community is serious. A Black person’s views on whether this country cares about social justice are obviously skewed [according to] those who have made it and feel they are successful and those who haven’t made it. For some, there is a tendency to play the race card and an unwillingness to do what it takes in many cases to succeed. And that is disturbing.

For white America, race is not on the majority agenda today. We have as a society corrected our worst abuses of degradation against blacks. Our actions say, “We have changed our laws, changed our actions, changed our thinking, and now it’s up to them.” Affirmative action is by and large not approved by white America. They think it’s enough already.

We’ve got a long way to go.