Conversations: Scott Avett

In archived interview, musician and artist talks about creative process, growth

In October 2019, Scott Avett was having the type of month multi-hyphenates dream about: a new album; a sold-out show at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center; an appearance on The Tonight Show; and the opening of a huge collection of his paintings at the North Carolina Museum of Art.

Six months later, the pandemic hit and the world came to a halt. Shows were cancelled and the debut of “Swept Away,” a new musical featuring the Avett Brothers music, was postponed for two years. During the first year of the pandemic, the group released a third “Gleam” album and Seth Avett recorded a series of Greg Brown covers while Scott focused on his visual art.

Back on the road since 2021, the group started its annual spring-summer tour in April. “Swept Away” now is scheduled to come to Washington, D.C., for a Nov. 25-Dec. 30 run at Arena Stage, with hopes for a Broadway debut in spring 2024.

The musical, which uses a dozen songs from the group’s catalog, is a different type of artistic challenge, Scott Avett told me in a 2019 interview.

“It seems so natural. Early, early, early on, I could see these songs as a Broadway piece, but I put that idea away years ago,” he said. “To see someone else imagine it or see it in the same way, that’s exciting. They’re producing something that may or may not work, but it will be fun to see what happens.”

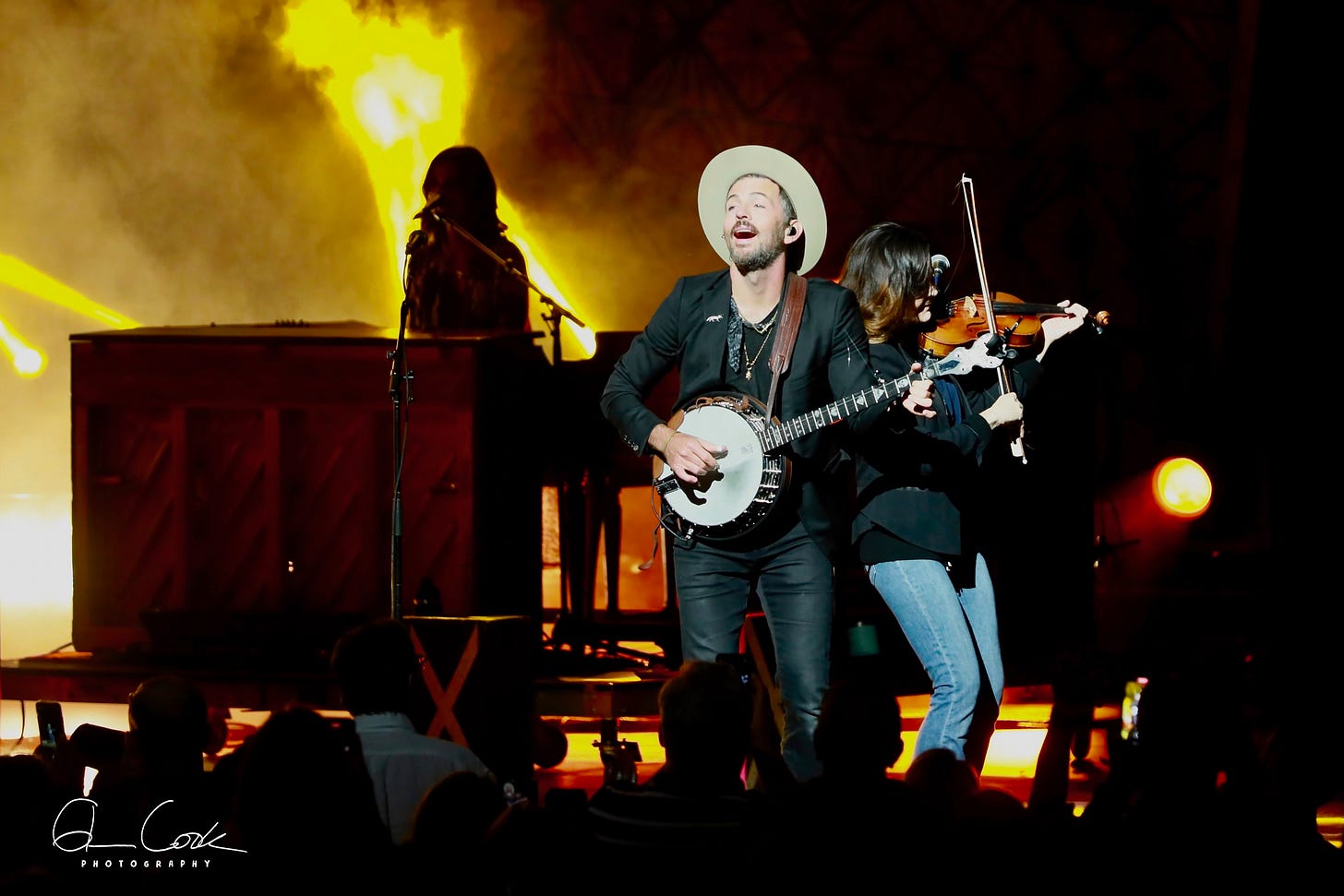

I’ve been fortunate to photograph the Avett Brothers four times — in 2018, 2021 and this past week at Wolf Trap and in 2019 at the Barclays Center. My interview with Scott came prior to the band’s release of their most recent full-length album, “Closer Than Together.”

Here are excerpts from that 30-minute conversation:

You refer to creating music as a form of “life and death output.” Can you elaborate on what you mean by that?

“By the end, there’s this output of life and death from ideas and thoughts. In some ways, it’s the death of songs in that we’ve recorded and released them, and yet there’s this new life that does reflect seasonal growth and dying off and rebirth. Creatively, it’s reflective of life and the trust we have in each other. But the songs have many lives and deaths as we are documenting them and putting them out there.

“I’m more aware of it than I used to be. I used to be so miffed by how short and grumpy I was at the end of every recording session. I would just be a total pain in the butt to live with. Seth would certainly agree. Now I’m much more aware of it and doing things to combat it.”

Judd Apatow directed a documentary based on the making of 2016’s “True Sadness,” which is your best-selling album to date. The documentary came out in 2017 on HBO and gave the album an additional boost. How did the film, which captured the intensity of the recording process and the changes that were taking place in your families’ lives, affect your approach to music making?

“’True Sadness’ had a little longer life because of that documentary, but the cool thing was we saw real numbers change at our live shows. More people came out who were curious, who had no idea what we were. It was sort of like, ‘Here’s this group. Why have I missed them?’

“It was exciting to see that growth in our concerts. That’s our real-time life, where we come and share all of these creative lives and deaths that we experience within a show.”

I can’t imagine what it must be like to see yourself in a documentary, especially one that dove so deeply into the creative process. What did you take away from it?

“Personally, seeing the documentary helped me observe how I responded to stress. I was able to observe this self I was on screen, this really unguarded, vulnerable self. Isn’t that amazing, that we can do that?

“We had the same process with (“Closer Than Together”) for sure, the same feelings for sure, but I did more to combat them and keep them in place, I tried to use the parts of them that are good to fuel what I do as opposed to stopping something in its tracks, which I’ve been known to do because I didn’t know what to do with it.”

How has the band evolved over the past two decades?

“Not everyone knows all the missteps and failures. There are all these hits and misses here and there. They always happen, but when one miss happens, the attitude has to be, ‘There will always be another opportunity.’ We have to know it’s OK, that there are always going to be misses. In fact, there should be more misses than hits.

“For the longest time, we always sort of ranked ourselves. Early on we had to do that, because no one was going to rank how we did. And we were very lucky. We were raised in a very caring — probably it’s a spiritual thing that I didn’t know at the time — environment in which you were encouraged to accept yourself as being part of something bigger and something grand.

“So, it’s a gradual evolution for me. It’s been in real time. I really don’t take any time to compare where we are consciously. Sometimes I forget where we sort of were or where (songs) came from. But when I think about it, I can certainly hear two different bands, especially as far as sound goes.”

How did signing with a major label — Rick Rubin’s American Recordings, now part of UMG — affect your trajectory?

“One of the things we did right, I think, is work amateur until you get called up into the quote-unquote majors, and I shouldn’t even put quotations around that. We started as amateurs (with the North Carolina label Ramseur Records). The majors would have been suicide for us. They really would have been.

“We knew how to draw thousands of people in several cities before we ever got to the majors. We knew how to sell records. We knew how to run a business. We knew how to write checks and manage money. We didn’t really need a major label at that point except to advance our creative process, and that’s where Rick came in.”

For a group that’s been so prolific, why did it take three years between albums?

“We’re more apt to take more time now than we used to. We didn’t used to have the financial ability to take the time, but as soon as we were remotely stable (financially), we started taking the time. It’s one of those resources I was talking about.

What has working with Rick done for your group?

“Right off the bat, Rick helped give us space that we weren’t taking for ourselves. We weren’t taking the initiative to make space and time at a natural pace. Rick has really helped us take time, make space for the music, and follow our instincts and conscience. We were on that path already but he really sped it up for us.”

How does your visual art — Avett’s paintings have been on the covers of several of the group’s CDs, most notably on “I and Love and You” — inform your music or vice versa?

“They’re large parts of who I am creatively, but they “can really distract each other badly. They can be each other’s worst enemy. I have to be really disciplined and know when to turn my back on one to work on the other.”

Touring for months at a time is exhausting, and you’ve talked about how difficult it is to be creative when you’re on the road. How long does it take for the muse to return?

“When I’m home and once I’m rested from being out, it’s so predictable, I get these visions of what’s next or these sounds of what’s next. They come in and I’m driven to go out and make whatever it is that calls me. But some of the most interesting stuff for me comes after the big efforts, when you’ve had the juices flowing and gears turning. Sometimes that lack of presence you feel because you’re so exhausted actually makes you more present. It causes you to be in real time and something great can happen. That’s really fascinating for my process.”

Do you enjoy music and art as much as you did when all of this started?

“I think I do. (Laughs) But in a different way. I try not to treat it as critically as I did 20 years ago, and that makes it more fun. It’s been a shift, because as many times as I say I’m going to change careers or going to quit, I never would. I’m always excited to move on to the next thing. There’s always the next thing to enjoy. I think that’s the key.”