Cutting Through the Noise

For true change to happen after school shooting, we must be urgent ... and patient

Since Tuesday, the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas has dominated most conversations, with noise coming in all directions.

At times, you think the noise will never stop.

And it doesn’t really, even though it eventually recedes to a faint whisper … until the next mass shooting inevitably occurs.

It you don’t believe me, look at the reactions following the horrific incidents in Las Vegas (60 deaths), Orlando (49 deaths), and Sandy Hook (26 deaths). Just two weeks ago, 10 were killed in Buffalo, N.Y.

Each time, we saw the universal platitudes that follow a mass shooting — sincere expressions of sympathy followed by walls of noise as everyone (including me) weighs in with opinions. Democrats call for measures to regulate guns and fight domestic terrorism; Republicans talk about the desire to double down on crime, how we need to “harden” our schools with security guards and single access points. They also point to the scourge of mental illness, which, BTW, they historically have done little to combat.

The result: Legislatures do nothing. Congress does nothing. Outrage dies down … until the next time.

And if history has proven anything, there will be a next time.

Generation Why?

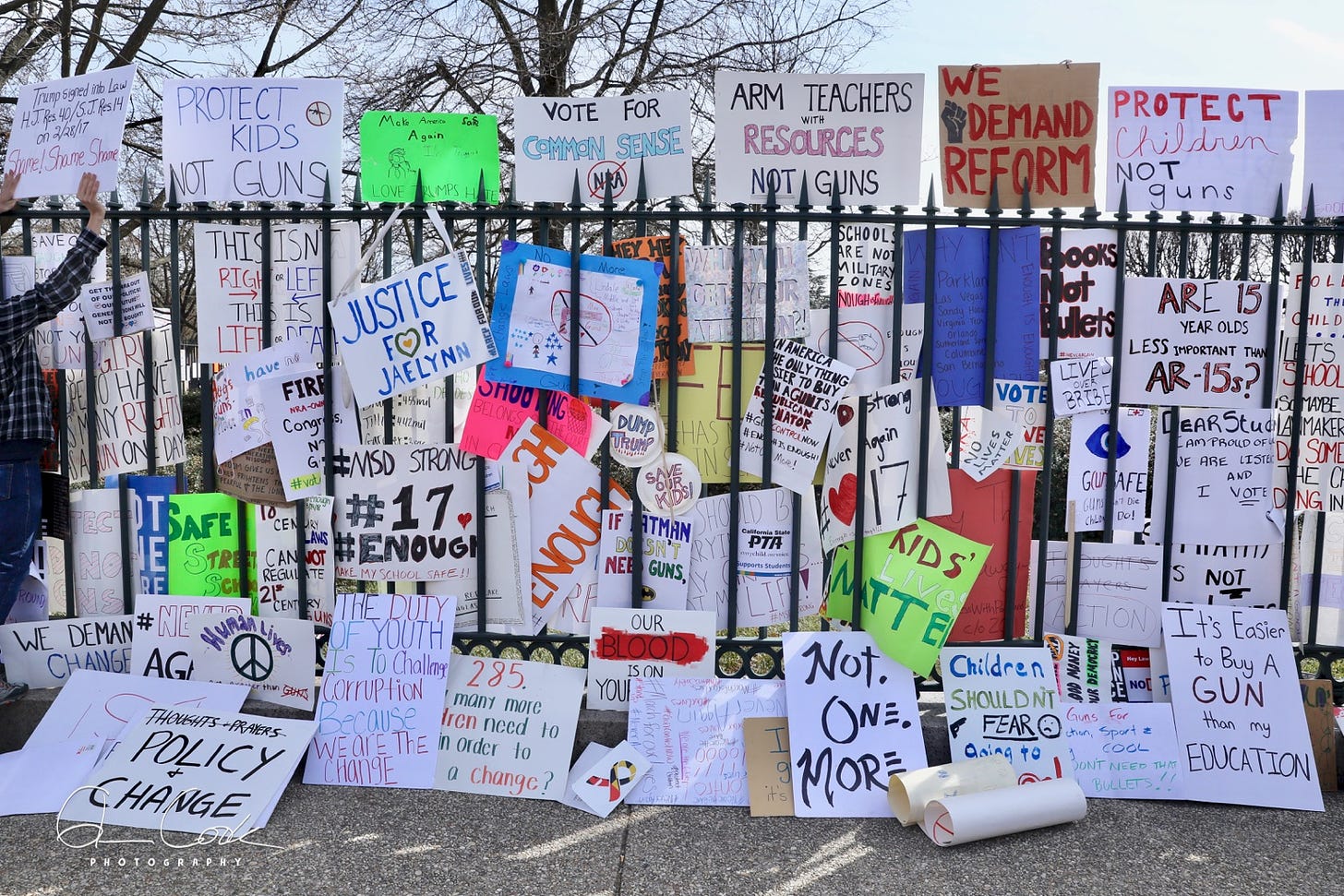

In 2018, I photographed the March for Our Lives protest in Washington, D.C., for a story I was writing on civic engagement — “Generation Why?” For the story, I interviewed students from all over the country at the march, which drew more than 1 million participants to our nation’s capital and to 800 other sites around the world.

The students held up signs with pointed remarks about gun violence. A group of youth carried a large banner — “Today We March. Tomorrow We Vote.”

And based on data following the 2020 election, they did.

According to Tufts University’s Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), roughly 50 percent of voters 18 to 24 cast ballots in the 2020 presidential election, which in turn had the highest turnout of any race in U.S. history. The number was up 11 percentage points from 2016 and is the highest since the voting age was lowered to 18, CIRCLE statistics showed.

In 2021, Harvard University’s annual Institute of Politics poll said 36 percent of young people describe themselves at “politically active,” compared to just 24 percent in 2010. That comes as Millennials and members of Gen Z — the groups of eligible voters born since 1981 — take a larger role in the potential outcome of elections.

Since the 2020 election, the culture wars — a powerful political lever for decades — have re-entered the news as local politics have taken on a national spin.And what’s on the culture wars menu — a variation of the “America: Love It or Leave It” bumper sticker from the 1960s — has become all too familiar as those in power for generations try desperately to hold onto it.

A Matter of Trust

“Trust” has become an interesting word in this country.

While yard signs and mailboxes proclaim people’s faith and “God Given Rights,” many of these same people don’t trust the election process. They don’t trust that a woman knows what is best for her and her body. They don’t trust that a person should know which gender they are assigned. They don’t believe this nation’s history narrative should deviate from the one taught for generations.

Think back to early May— yes, earlier this month — when all these issues were in the headlines. Don’t think for one second they won’t re-emerge when this news cycle comes to its inevitable end.

And don’t forget for a second that these same people trust a process that allows an 18-year-old male without a driver’s license to purchase guns and ammo that could annihilate an entire classroom of children. Or how when that happens, they ask for “civility” instead of outrage. While pointing the finger at others and demanding accountability, they ask you to trust them to get to the bottom of this.

Earlier this week, Roxanne Gay, an author and opinion writer for the New York Times, made the point far more articulately than I can:

“When politicians talk about civility and public discourse, what they’re really saying is that they would prefer for people to remain silent in the face of injustice. They want marginalized people to accept that the conditions of oppression are unalterable facts of life. They want to luxuriate in the power they hold, where they never have to compromise, never have to confront their consciences or lack thereof, never have to face the consequences of their inaction.

“They call for civility, but the definition of civility is malleable and ever-changing. Civility is whatever enables them to wield power without question or challenge.”

Hmmm…

Separating Gun Violence and Mental Health

Given much of my professional life is devoted to writing about public education, and all my wife’s work is about helping those charged with providing counsel and advice to students who need their help, it should come as no surprise that this week’s events have derailed both of us. Jill, as the leader of her organization, has dealt with myriad issues all week, from media interviews to blowback from those who refer to this as a mental health issue and not about gun violence.

What happened on Tuesday, regardless of what others may say or think, is not about mental health. It is about a deeply disturbed person who, with ready access to an AR-15, committed a heinous act that resulted in the deaths of 19 children and two adults.

In an essay after Tuesday’s tragedy, I noted the majority of mass shootings occur because someone who is mentally ill — and usually untreated — gains access to a firearm. At the same time, conflating a mass shooting with mental illness only muddies the point. Most people with mental health issues are not violent, and statistics bear that out. In fact, more often than not, the mentally ill are the victims of violence.

Unfortunately, the gun lobby has deeper pockets than the mental health lobby.

Why does a young person who cannot legally purchase a beer buy and have access to a semiautomatic weapon? It’s due to antiquated laws that, at least in Texas, date back to the 19th century.

Historian Brennan Rivas told the Texas Tribune that the legislature “started specifically targeting weapons that they equated with crime,” such as bowie knives, daggers, and pistols. Rifles and shotguns were excluded because they had “valuable uses.” Today, only six states — California, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Vermont, and Washington — prevent someone under 21 from purchasing long guns, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

Most of those laws were passed following the school shooting in Parkland, but the Texas Legislature moved in the opposite direction following the 2018 massacre at Santa Fe High School (10 deaths) as well as high profile shootings in 2019 in El Paso (23 deaths) and Midland and Odessa (eight deaths, 25 injured). Texas residents can now carry handguns in public without a permit or training and into hotel rooms.

For those who say armed officers should be patrolling our schools, all I have to do is point to Parkland and sadly, Uvalde, as examples where it didn’t do any good. On Friday, the director of the Texas Department of Public Safety said the school district’s police chief made the wrong call when he treated the Uvalde suspect as a “barricaded subject” instead of an active shooter.

“Of course it was not the right decision,” Steven C. McCraw said during a press conference. “It was a wrong decision, period. There’s no excuse for that. When there’s an active shooter, the rules change.”

And yet, somehow, we continue to think that armed officers without training in dealing with children are our best bet for school safety. Active shooter training calls for officers to rush in during a situation, not listen to gunfire from behind a door or hide out of site.

True Change Takes Time

Following Tuesday’s shooting, the student-led March for Our Lives group announced they will hold another protest in Washington, D.C., on June 11. On Thursday, students across the country walked out of school to protest gun violence.

These protests are likely to re-energize youth interest in voting, which is particularly critical as we get close to the 2022 midterm elections. And one hopes that it will reverse a troubling but familiar trend: Young people feeling like political involvement and their votes don’t make a real difference.

That disenchantment with an entrenched process makes sense, following the intense culture wars response to issues important to youth and given the lack of legislative action following the murder of George Floyd and others by police in 2020.

As I’ve written previously, protests are great, but without action fatigue and resentment will set in. Passion will fade and the status quo will return.

If you need an example of this, look at a piece of Uvalde’s history. In 1970, students staged a 39-day walkout to protest discrimination against Mexican-American students. The walkout led to a class action lawsuit filed by Genoveva Morales, a mother of nine, against the school district.

Five years later, the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled the district had failed to desegregate and put Uvalde under a court order. It took until 2008 — 38 years after the initial walkout — for the order to be lifted.

Instant gratification is a myth. The process of change takes time and consistent, long-term effort, a constant filtering of the noise that surrounds us all.

Great post, Glenn. So well said.