From First to Footnote

The roots of school desegregation are found in Summerton, S.C., but progress has not had much chance in this small town

From April 2004 — American School Board Journal

The story of Summerton and its schools is a footnote to history.

On the surface, daily life in this small South Carolina town today is a far cry from that of a half century ago. At the same time, little seems to have changed — and many residents seem to prefer it that way.

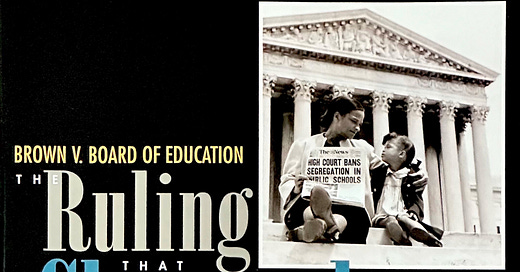

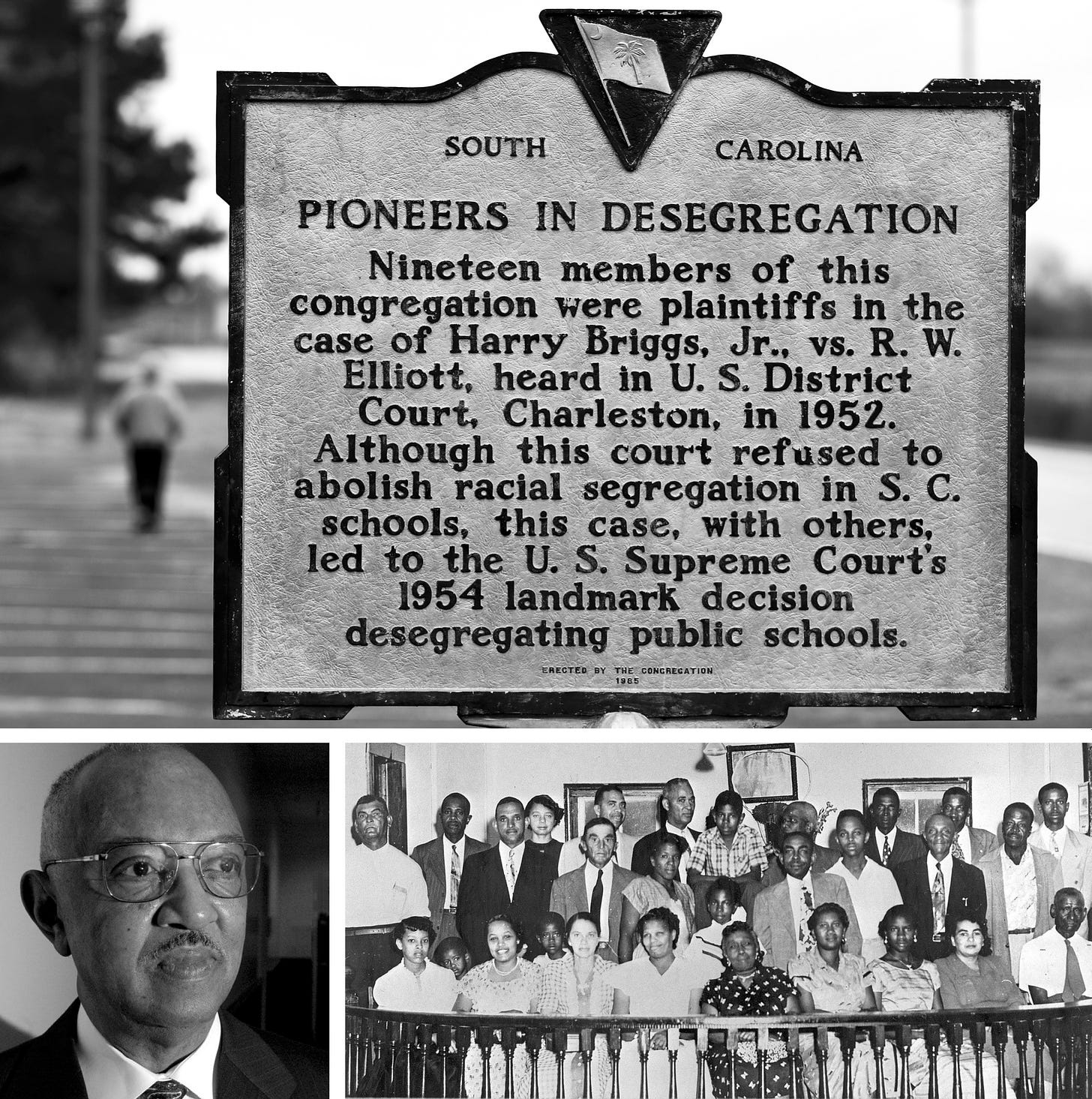

And with good reason, for the townspeople — especially whites — continue to cast a wary eye at Summerton’s place in history. The town is home to Briggs v. Elliott, the first of five cases later consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education and arguably the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.

To most people, Brown is the story of a lawsuit that occurred because an African-American girl from Kansas was not allowed to attend an all-white school. But legal observers note that Briggs — not Brown — provided the foundation for the abolishment of separate but equal schools. Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP lawyer who led the battle to end segregation in America’s classrooms, argued Briggs — not Brown — before the Supreme Court.

“This is where it began. It all started here,” says Joe DeLaine Jr., the namesake and son of the pastor whose efforts led to the landmark litigation. “And yet people don’t want to acknowledge it. They would be happy if it all just went away.”

But DeLaine and descendants of the original plaintiffs — many of whom left South Carolina and returned after retiring — are working to change that. Now in their 60s and 70s, they want Summerton to acknowledge and embrace its place in history. They want this hamlet — still dominated in population by blacks and in power by whites — to educate its children equally and equitably.

In some ways, the task is as onerous — although not as physically or economically threatening — as that of their parents and grandparents. Because while Summerton is technically desegregated, it is far from integrated. Fifty years after Brown, it is a place where separate still exists, and equal remains just out of its grasp.

Separate Worlds

The other Brown districts — in Delaware, Kansas, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. — have largely embraced their role in the desegregation movement over the past decade, converting old schools into museums and using the 50th anniversary to salve the scars of the past.

Summerton’s efforts have been limited to the establishment of an interracial economic development group and a monthly men’s prayer gathering that is held in various white and black churches. Town leaders are quick to note the high school and the private school now play against each other in sports, and that whites and blacks mix when an entertainer — Pat Boone this past Christmas — performs in the auditorium next to the school district’s central office.

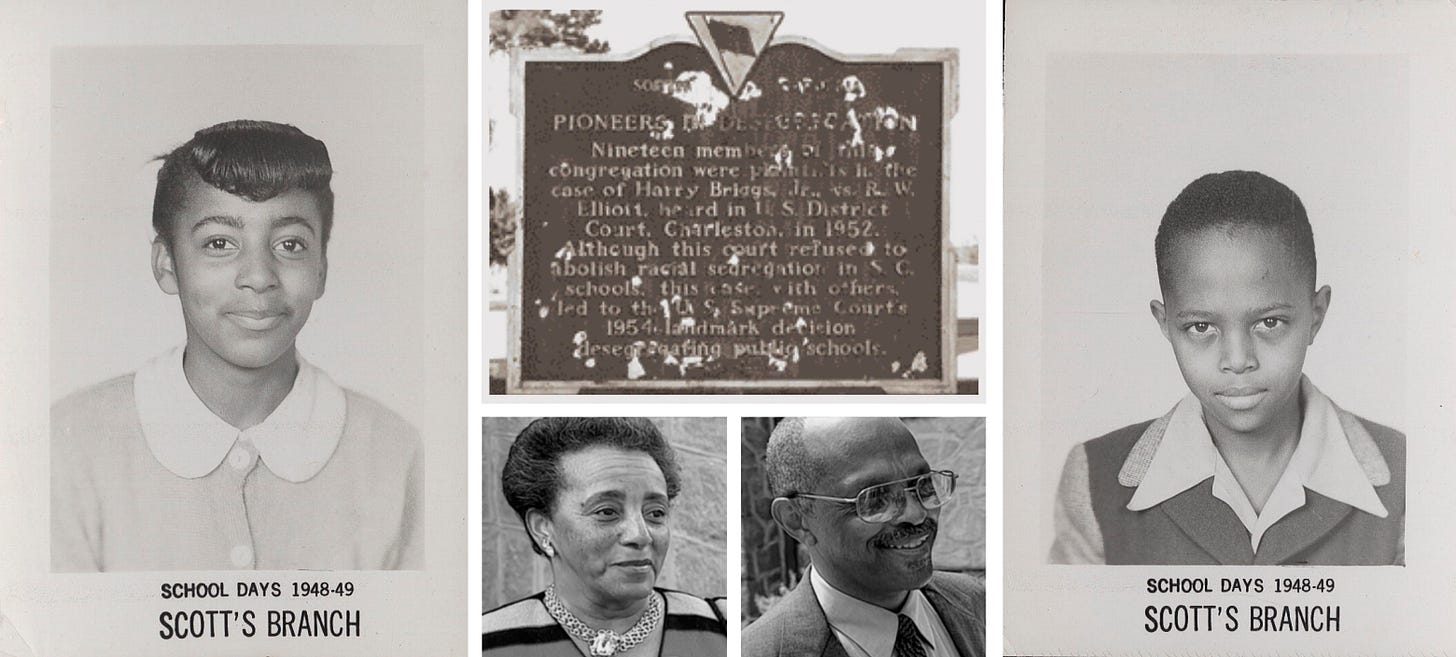

Signs leading to Summerton can be seen by travelers on Interstate 95, but one road sign is a fitting irony in this town of contradictions. Earlier this year, as historic markers that tell the Briggs v. Elliott story remained chipped and fading, town leaders celebrated the renaming of U.S. 15 as the Althea Gibson Highway. While it’s nice to honor a native who became a tennis star — the first African-American woman to win Wimbledon — Gibson left Summerton at age 3 and never returned.

Beatrice Rivers came back to Summerton to live and wishes she hadn’t. A child when her father, Henry Brown, signed the Briggs v. Elliott petition, she returned to Summerton to care for her aging mother almost a decade ago. Rivers vividly remembers the petitioners’ struggles, the jobs that were lost, the families left broken when fathers had to leave their wives and children to make a living elsewhere. What she hasn’t seen are many signs of progress.

“I don’t see much change here,” Rivers says. “Summerton is still two separate worlds. And the blacks and whites don’t interact much, if at all, unless they have to. It’s no different really.”

Some people say class relations, not race relations, are the problem. Located about 65 miles southeast of Columbia, the state capital, Summerton is part of South Carolina’s rural “Black Belt,” a stretch of farmland with little industry and high poverty. More than 95 percent of the 1,288 students in Clarendon County School District No. 1, which serves Summerton and the surrounding area, are eligible to receive free and reduced-price lunch.

Of the districts involved in the Brown decision, Clarendon No. 1 had — and continues to have — the largest percentage of minority students. In 1949, about 75 percent of school-age children in Clarendon County were black; today, Summerton’s three schools are 95 percent black, 3 percent white, and 2 percent Hispanic. The vast majority of white students attend Clarendon Hall, a private school that opened in the mid 1960s to blunt integration efforts.

“I don’t like it,” Rivers says of living in Summerton. “I wish I was back in Washington almost every day. Many days I wish I was anywhere but here.”

Rivers and her brother, Harrison Brown, are dedicated to the Briggs-DeLaine-Pearson Foundation, a group that is working to raise awareness about Summerton’s place in history. In 2002, Joe DeLaine, Rivers, Brown, and others wrested control of its operations from longtime residents who, in DeLaine’s words, “had done nothing, not a damn thing.”

Today, some of those residents complain that “outsiders” now populate the foundation’s board, noting Brown lives in Sumter, and DeLaine and his brother, Brumit, are in Charlotte, N.C. But the foundation’s leaders say they are committed, and their actions bear it out. They’ve talked to Scott’s Branch High School students who are working on an oral history of the lawsuit, and they’re trying to raise money for a memorial fitting of Briggs v. Elliott’s legacy.

Even more important, they’re telling their story wherever they can. And what a story it is.

Drawing the Line

It started, quite simply it seems today, over a bus.

In 1947, African-American children who lived in and around Summerton did not care how they got to school. They just didn’t want to walk — in some cases 15 or 16 miles from the district’s outskirts — while white children passed by on a bus.

Schools for black children had no running water or indoor toilets. Students studied in oneand two-room buildings with only two or three teachers, with one of the teachers doubling as the principal. In Summerton, J.A. DeLaine — an educated man who also served as an AME minister — filled the dual role at Liberty Hill School.

“He had a reputation among most of the communities down there because he made himself involved with people,” his son Joe says. “If he went to visit Mr. Jones and Mr. Jones was picking cotton, then my father went right out to the cotton field in his suit and picked some cotton. If Mr. Jones was plowing, he’d say, ‘Here let me have the plow and you rest for a minute while I talk to you.’ He came across as one of them.”

Clarendon County spent almost two-thirds of its education budget to educate white children and paid no money to transport black youth to school. Or, as school board chairman R.M. Elliott told farmer Levi Pearson and others: “We ain’t got no money to buy a bus for your n----- children.”

DeLaine, like many black ministers of the era, was becoming heavily involved in the NAACP. In June 1947, at a state NAACP meeting in Columbia, DeLaine heard State President James Hinton challenge the audience. Find someone, Hinton said, who will sue the system for school transportation.

“Daddy was always for the underdog,” says Brumit “B.B.” DeLaine. “He didn’t care whether the underdog was black or white. It’s a natural instinct that when people have been pushed so far down that they are kind of forced to get up. Things had gotten so bad, that he had to stop and say, ‘Enough is enough.’”

DeLaine drove home and found Pearson, who with other area farmers had purchased a secondhand bus that kept breaking down. The school district refused to pay for gas, much less repairs.

Prodded by his pastor, Pearson filed a lawsuit, but Pearson v. Clarendon County was dismissed in June 1948 on a technicality. According to court records, the land that Pearson farmed was within the school district’s boundaries, but his home wasn’t.

The line in the sand — or dirt as it may be — had been drawn. In many ways it remains there today.

Suing for Equal Opportunity

By the late 1940s, Thurgood Marshall was a rising star in the NAACP, which was taking a targeted approach to improve conditions in black schools across the nation. Marshall knew a lawsuit in the South faced huge hurdles due to the entrenched segregation that existed, and he hoped to find the test case for equal schools elsewhere.

In the spring of 1949, he met with Pearson and DeLaine in Columbia. By day’s end, Marshall agreed to file a lawsuit for equal school facilities if they could get 100 signatures on a petition. Pearson and DeLaine started to work, and 107 had signed on by the fall. At the top of the list were Harry Briggs, a gas station employee, and his wife, Eliza, who worked as a maid at the local hotel.

When Briggs v. Elliott was filed in U.S. District Court later that year, it asked for equal educational opportunities but did not seek to end segregation. Still, the payback from Clarendon County’s white community came quickly. Harry Briggs lost his job, as did his wife and many others. The petition’s signers suddenly could not get fertilizer for their fields or find buyers for their crops; a number lost their mortgages.

DeLaine was fired from his teaching job but continued to lead from the pulpit. In 1951, firefighters watched his house — 20 feet outside city limits — burn to the ground without turning on their hoses. DeLaine transferred to an AME church 50 miles away in Lake City but continued his work.

“The method of intimidation against African Americans made many fearful of challenging the policies that existed,” his oldest son says. “They were literally risking their lives. You didn’t have to be told you were in jeopardy. You knew it.”

The father of Denia Stukes Hightower was a petitioner. After the lawsuit was filed, he lost his job and tried to make a living as an auto mechanic at his home. He was crushed by a car in circumstances some still claim are suspicious. The rest of the family fled to Philadelphia, but they remained plaintiffs in the lawsuit, picking up news of the proceedings from afar.

“No one took their names off the petition,” Hightower says. “They decided you have to fight them. The wives threatened the husbands that they were going to quit them if they took their names off that petition. No one was broken.”

Suing for Desegregation

Many white Southerners, especially those who grew up under segregation, rationalize their ancestors’ actions by calling them “products of their time.” But some, like J. Waties Waring, took stands against the common attitudes of their day.

Waring, a U.S. District Court judge who came from a family of white Charleston aristocrats, fought against his privileged heritage. In the 1940s and ’50s, as Strom Thurmond touted segregationist practices and ran for president on a “Dixiecrat ticket,” Waring took numerous positions that supported blacks. His rulings forced the state Democratic Party to integrate and required school districts to pay teachers the same salary regardless of race.

“Judge Waring is truly the unsung hero in all of this,” Joe DeLaine says. “He is the first judge that I am aware of who objectively ruled on the merits of the cases rather than on the race of the individual. The African Americans of South Carolina saw him as someone who would give them a fair hearing in his courtroom.”

As Briggs v. Elliott moved its way through the court system, Waring urged Marshall to refile the lawsuit, saying the case was not about equal facilities but about segregation itself. Marshall took Waring’s advice. In June 1951, a three-judge panel voted 2-1 to require South Carolina to provide equal facilities for black and white students.

The ruling — considered a compromise by whites in South Carolina — was closely watched in other states faced with similar lawsuits. In an extraordinary 28-page dissent, Waring included a phrase that would be used as a blueprint by the U.S. Supreme Court three years later.

“Segregation in education,” he wrote, “can never produce equality.”

At the time, all decisions by three-judge panels automatically were appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The NAACP filed the same lawsuit in four other states; the appeals were consolidated into one case.

Even though Briggs was filed first, and Marshall argued its merits before the Supreme Court, the case became known as Brown v. Board of Education — the lawsuit that had been filed in Topeka, Kan.

Some theorize that Brown became the lead case because it was from the Midwest and the court did not want Southern politics to blunt the impact of a potential ruling. In 2002, U.S. Sen. Fritz Hollings told a reunion of the Briggs descendants that it was because Topeka’s schools were partially integrated.

Amid the conjecture, and despite volumes of research on the cases, no one really knows for sure.

The aftermath

The days immediately after the May 17, 1954, decision were happy ones for Summerton’s black families, although there were no open celebrations. In Lake City, the Rev. J.A. DeLaine continued to face threats.

In October 1955, a few months after the Supreme Court ruled schools should be integrated with “all deliberate speed,” whites threatened to kill DeLaine if he did not leave town. A week later, his church was burned; on the 10th day after the threat, DeLaine heard gunfire outside his home. He fired two shots at cars in the street, hoping to mark the vehicles as the sheriff had told him to do, then fled his home state.

“The uncertainty was traumatic because for several days I had no idea where he was,” his son B.B. says. “It took us three days to find him.”

DeLaine, heading for New York, was never found by authorities who had taken out a warrant for his arrest. In Buffalo, he reestablished himself as a teacher and founded the DeLaine-Waring AME Church, naming it after the judge who had moved to New York under his own cloud of controversy. Waring, who retired from the bench under pressure in 1952, returned to South Carolina to be buried in 1968. Attending his funeral were 300 blacks; the only whites were family members.

The state of South Carolina, bowing to political pressure from the federal government, never pursued extradition against DeLaine, but he never returned to his home state. The arrest warrant remained active for 26 years after his 1974 death in Charlotte; in 2000, he was pardoned posthumously.

Summerton’s schools have faced an uphill battle as well. In 1966, the first blacks were allowed to attend the all-white Summerton High School. But many white students already had left for Clarendon Hall, which had opened the year before.

“In Summerton, when the whites left, they said they would never come back, and they haven’t,” says Leola Parks, executive assistant to Clarendon No. 1 Superintendent Clayton Willie and one of the first blacks to attend Summerton High (now Scott’s Branch).

White parents interviewed — none on the record — say they believe Clarendon Hall’s academics are better. Numbers over time back them up: Scott’s Branch students average only 761 on the SAT, compared with Clarendon Hall’s 978.

Constance Hill, a teacher at Scott’s Branch High, says some white students want to attend the public schools. Parents, she believes, continue to be the major obstacles.

“We’ve had some students come in from the private school to take standardized tests, and some of our students talked with them,” Hill says. “The kids from the private school said they wished they could be here, but it’s their parents. ... Their parents say they can’t come.”

Seeking a Boost

Clarendon No. 1’s high poverty rates and low achievement have resulted in a vicious cycle. Financial struggles have forced cuts in staff the past two years. Meanwhile, an early childhood center — considered key to boosting student achievement — sits half-finished behind the central office for lack of funds.

The district is also one of 36 that have sued the state over a lack of adequate funding. Ironically, the lawsuit is being heard at a courthouse in Manning, the Clarendon County seat that is only 14 miles away.

Since he was hired in 2002, the superintendent has taken steps to boost achievement. He has cleaned house — all three schools have new principals — and pushed for more staff development and parent involvement. A facilities plan is in place and Willie wants the board to seek a bond referendum this spring.

Willie, who came to Clarendon County from North Carolina, says his biggest struggle is changing the mindset he found in Summerton, one that exists even among some teachers. To illustrate, he tells of meeting a white teacher during his first week on the job.

“I’d heard we had white teachers, more than we had white students, so I was pleased to see her,” says Willie, who is black. “I asked her a few questions: Do you live in Summerton? ‘Yes, yes. I’ve lived here all my life.’ Do you have children? ‘Yes.’ Where do they go to school? ‘Clarendon Hall.’ And that’s when the conversation ended.”

He shakes his head. “The way people relate here to each other, black and white, you see no obvious differences,” he says. “But there is that line. When you talk about children in the schools here, there’s a line you just don’t cross.”

The Pull of the Past

As the 50th anniversary nears, attention is finally being paid to the legacy of J.A. DeLaine, largely due to the efforts of his oldest son.

For the past several years, Joe DeLaine has been the family’s public face. He serves on the federal Brown v. Board Commission as one of South Carolina’s two representatives. He is the person quoted most often in the press and is known as someone who doesn’t mince words about anything, especially the lack of attention paid to Briggs v. Elliott.

The irony, he notes, is he has wanted to run away from home since he was a child. DeLaine has harbored a desire for decades to live in Europe, where he says race issues don’t exist the way they do in the South. And yet, after spending his professional career as a pharmaceutical executive in New Jersey, he now lives in the last house his parents owned.

Today, that house on Washington Street in Charlotte is only a few miles from the museum where Briggs v. Elliott is finally getting its due.

The Levine Museum of the New South, which showcases stories about the post-Civil War South, opened an eight-month exhibit in late January titled “Courage: The Carolina Story That Changed America.” All three DeLaine children, including middle child Ophelia, participated in the project; her school picture serves as the focal point of the museum’s posters and promotional materials.

A retired college professor who lives in New Jersey, Ophelia DeLaine Gona rarely sits for interviews. Like her brother B.B., she’d rather work behind the scenes and let Joe be the spokesman.

But like others who have left and returned to Summerton, she also feels the pull of the past. With her brothers, Ophelia sat for extended interviews that are being used in the museum’s interactive exhibit. She helped select photographs and resource materials from her father’s extensive files. She also spoke to Scott’s Branch students who attended the opening as part of their oral history project, telling them to remember and to achieve.

“You young people have a responsibility to get an education. You have a responsibility to act nice,” Ophelia told the students. “I’m not talking about goodie, goodie. You have a responsibility to act a certain way. You have a responsibility not to be ground down in the dirt. It is your responsibility to succeed.”

Crossing the Line

Joe Elliott knows, deep down, he has crossed Summerton’s invisible line. The grandson of Briggs defendant R.M. Elliott has become, as one resident says, the “Judge Waring of his time.”

A sixth-generation Summerton resident, his ancestors came to South Carolina in 1690. Elliott lives in the plantation-style home, tucked away on a dirt road on Summerton’s outskirts, that his mother’s family has owned for almost 200 years.

Elliott, an amateur historian, is proud of his heritage. In a tour of his house, he points to pictures of relatives who served as Confederate officers and notes his lineage includes at least four men who were South Carolina governors. But he’s also proud that he helped integrate the Greenwood County elementary school, where he served as principal, and that he has tried to promote better race relations in Summerton.

“We won’t ever move ahead as long as the blacks demonize the defendants, and as long as the whites refuse to acknowledge the bravery and courage of these plaintiffs,” says Elliott, who was 9 when the Briggs lawsuit was filed. “They took on an institution. They took on the entire South. The blacks in this community changed not just the nation, but the entire world.”

In 1998, Elliott took over as headmaster at Clarendon Hall. Some blacks pointed to his heritage and said he was just carrying on the family tradition. In his three years at the school, Elliott reached out to Clarendon No. 1, promoting basketball games and holiday concerts between the two. He also helped organize a biracial group to discuss race issues.

But when he started speaking out publicly against the separation that still exists in Summerton, he saw firsthand how difficult it is to change minds. In 2003, with the federal Brown v. Board Commission planning to visit, the mayor asked Elliott to speak to white civic groups and urge them to take part. The reaction to his plea to one well-established organization, he says, was “very disheartening.”

“I saw several of my long-time friends there, one close friend in particular. The whole time I was talking he looked away and drew on a piece of paper,” Elliott says. “Needless to say, I didn’t get a standing ovation. With typical Southern politeness a couple of them said, ‘Good job. Thank you for coming,’ before they moved on with business. My old friend — he didn’t say anything. And he’s hardly spoken to me since.

“A lot of people used to call me Joe. Now they talk to me but don’t call me by name,” he says, shaking his head. “It’s not ostracism. I can’t be ostracized in Summerton because my family has been here so long. But there is a tension that I’ve never felt before. It’s as if people don’t care.”

Reaching Out

At the end of the Levine Museum’s two-day opening, family and friends gather at Joe DeLaine’s house for an informal supper. Food, as it is at each of these gatherings, is plentiful. Scattered throughout the house, the young and old eat, talk, and laugh, sharing stories and catching up before going home.

As everyone starts to leave, Joe steps outside and lights a cigarette. “I’m exhausted,” he says, cupping it in his hand. “But this is good. It’s been good.”

For a man of 70, Joe DeLaine keeps a schedule that intimidates people half his age, all to tell a story he believes can’t be told enough. Soon there will be more appearances, meetings, speeches, interviews. A ceremony and banquet sponsored by the Briggs-DeLaine-Pearson Foundation is planned, followed by the actual anniversary of a day some thought would never come.

Also planned: A ceremony awarding the Congressional Medal of Honor posthumously to J.A. DeLaine, Levi Pearson, and Harry and Eliza Briggs. At last, it represents national recognition for their efforts, first for a bus, but ultimately for the nation’s schoolchildren.

Summerton’s work is far from done, however. And that’s one reason Joe DeLaine says he’s planning to call Joe Elliott.

“I need to reach out to him,” he says before stepping back inside. “It’s not fair the way he’s being treated here.”