Conversations: Dave Alvin, Part 1

Legendary songwriter talks about New Highway, playing live again after cancer battle

Dave Alvin rocking in Washington, D.C., in 2018.

After more than 40 years on the road, Dave Alvin is itching to get back on the highway again.

“Playing live is what I love to do more than anything. That's just it for me,” says Alvin, the legendary California singer-songwriter and guitarist. “It’s my religion. That’s how I go to church. I can’t go hiking in the mountains, but I want to play music live.”

At times over the past two and a half years, as he fought through three separate cancer diagnoses, surgery, chemotherapy, and a painful battle with neuropathy, Alvin questioned whether he would be able to play music again, let alone in front of an audience. Now cancer-free, the 66-year-old is performing select dates on the West Coast with friend and collaborator Jimmie Dale Gilmore. Last month, he also sat in for a reunion show with the original Blasters, the group he formed with his brother Phil in 1979.

“I always knew I was a lucky guy to have a career that's lasted this long,” Alvin said during a recent phone interview. “That just doesn't happen very often. I always knew that each day could be your last and not only in your life but in your career. To go back and do it again after two and a half years was just … I felt 21 again.”

“I don't like to use hackneyed terms like a ‘rebirth,’ but that's what it was. I just felt like, ‘Okay, let's go around the world. Let's go make records, let's go tour. Let's go.’ That's how I feel right now.”

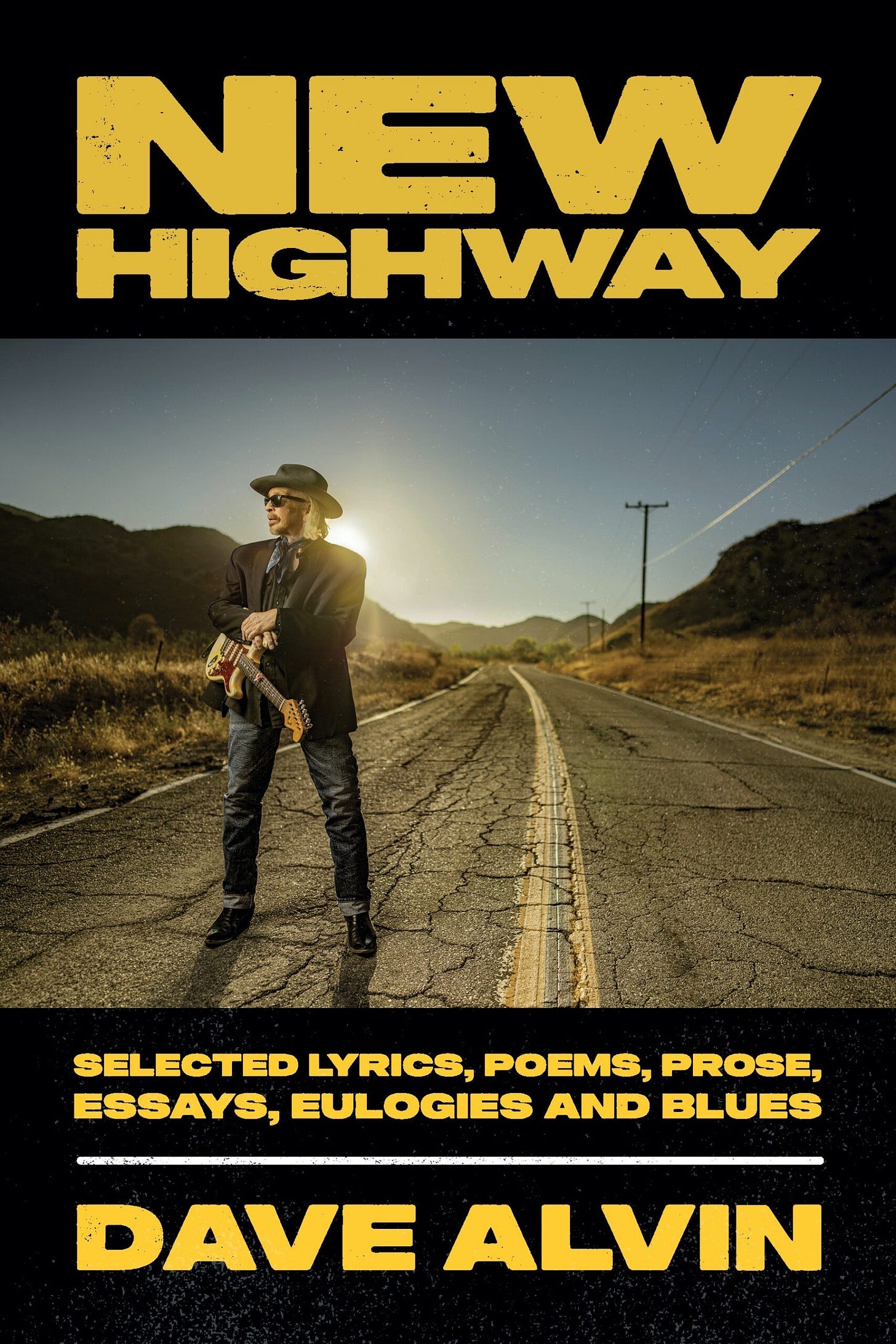

On the advice of his doctors, Alvin is staying close to home through the end of the year. Plans are to start touring in force in 2023, but in the interim, he is working on a memoir and promoting New Highway (BMG), a collection of lyrics, poems, eulogies, and short stories written during his four-plus decades in music.

The 240-page book includes Alvin’s lyrics to almost 50 songs, some dating back to his days with The Blasters and covering a large swath of his solo career. He writes about encounters with Buck Owens, Ray Charles, Big Joe Turner, and Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Records, and pays tribute in eulogies to collaborators Chris Gaffney and saxophone player Lee Allen, among others. It is an excellent read, and a fantastic primer for the promised memoir.

I first saw Alvin in the mid 1980s with The Blasters at the legendary Fitzgerald’s nightclub in Houston (where Stevie Ray Vaughn got his start). He left The Blasters in 1985, worked as a sideman with X (writing the classic “Fourth of July” for their 1987 album “See How We Are”), and went solo in 1987. Since then, I’ve seen him in concert more than 20 times, including shows with The Knitters, The Pleasure Barons, and the reunited Flesh Eaters.

We spoke for an hour about New Highway, Alvin’s health and return to the stage, and some of his future plans. He was self-effacing, funny, serious, and grateful to be in a better place.

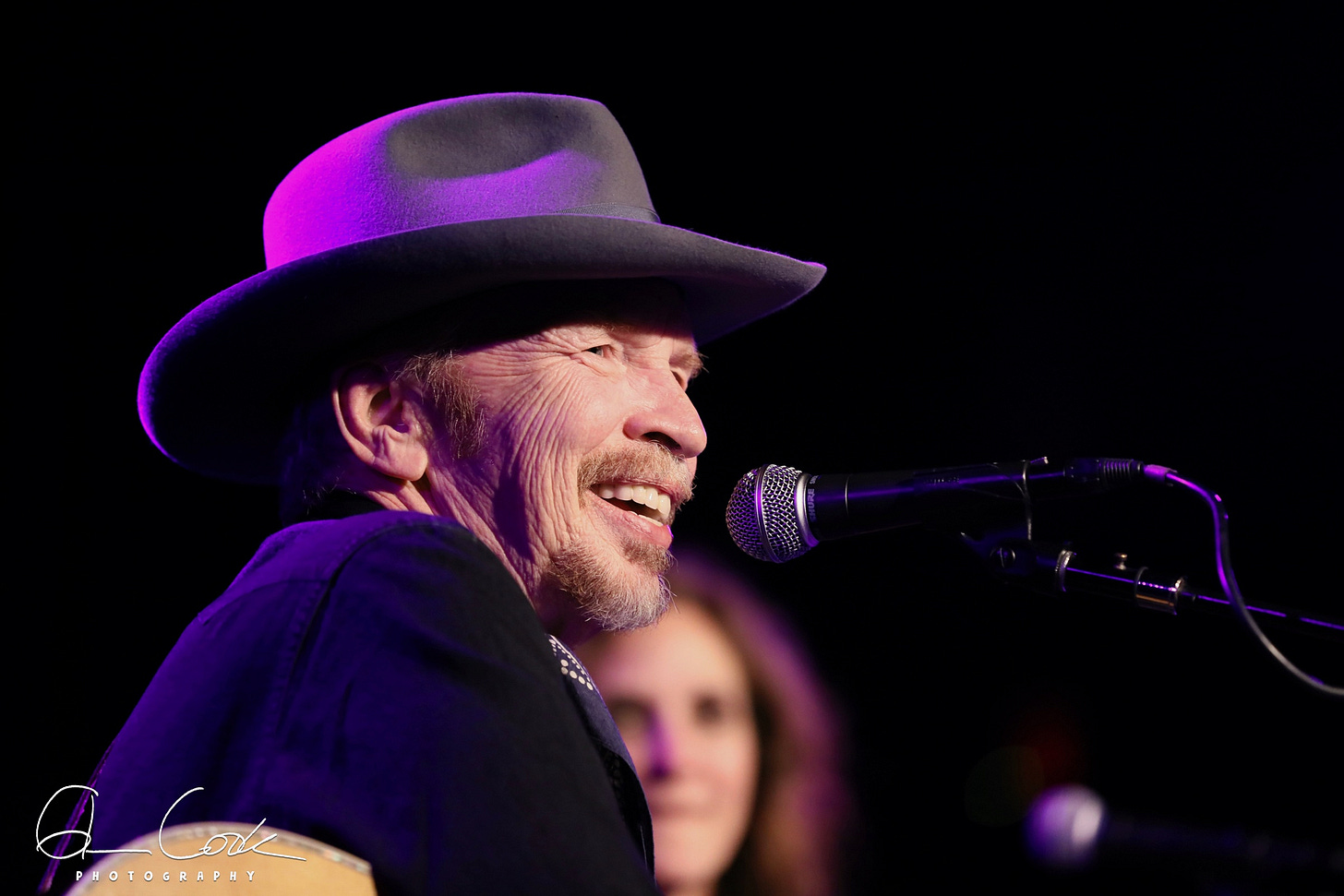

Dave Alvin talks to the audience during the 25th anniversary tour for King of California — Alexandria, Va., 2019

Below are excerpts from our conversation, with edits for length and clarity.

How are you feeling?

Dave: I feel pretty good actually, and at times I feel downright normal. I developed neuropathy from the chemotherapy I had and the radiation treatments as one of my cancer pals. When you have cancer, sometimes it's not cancer that gives you pain, it's the treatment.

For about six months after I started chemo, I couldn't play guitar. Some people said I never did anyway, but I literally couldn't touch the guitar. My hand was so swollen and painful. It was weird, it was surreal, but you just plow ahead.

How does it feel to be making a slow steady path to public re-emergence, and getting back on stage?

Dave: You come out of these things or you develop in these things. When you have cancer, part of the problem is what chemotherapy and those kinds of things can do to your brain. You have dark thoughts at times. There were times when I thought, ‘Well, I guess that's done, I'll never play music live again and maybe I'll never play music again.’ To actually be able to do it again, it was just like, I can't tell you.

I shoot and review lots of concerts, and during COVID, I really missed the connections you make with people at the shows. That was the hardest part of the last two years for me. I can’t imagine adding cancer on top of it.

Dave: For people that like odd music like I play, not the stuff that is on the top 40, but blues, singer-songwriters, or a loud attitude punk rock band, part of the joy is the sense of community with the audience and the band. To be deprived of that was really, really rough for the audience and the musicians. Everybody had a hard time, so getting out there again is therapeutic for all of us. I felt that at every (recent) gig. I can’t believe I’m going to use this term, but you really could feel the love and it was really moving.

What made you want to do this book?

Dave: I've been meaning to do a book like this and a memoir and all that jazz, but I was too busy. (Alvin toured for 10 months in 2019, a common pre-cancer schedule.) Between COVID and cancer, certainly I had time on my hands, and it was like, ‘Let's go through all the songs. Let's find the order that they sort of work in my brain, and let's gather up all the music writings that I've done. Let's put them all into one book and then that'll be the primer for the memoir to come.’

I was making plans to do it with a a particular small press because I figured that's probably where it belonged. That way no one would tell me what to do, like my record label. But then Scott Bomar (publisher and senior director of BMG Books) approached me out of the blue and said, ‘Hey, you want to do a couple of books with us?’

Scott is a great writer and a great music historian. I’ve been a big fan of his writing for a while, so having him call me up and say, ‘You want to do this?’ Let’s do it; I’m all in.

Describe your writing process. Do you just jot stuff down in a notebook and come back to it? Does it come to you organically? How do you work?

Dave: Some stuff is just branded into my brain, like the (essays) about Joe Turner or Johnny Otis. Sometimes, if I'm talking to somebody and somebody starts saying stuff that starts registering, I think, ‘Oh, this could be a song, or this could be a poem, or this could be just a funny story.’ It just clicks in and my mind tape records it.

It's a weird thing. I've just trained my brain to do that. Some stuff I write down when it happens, like when somebody says a funny line. But I just remember a lot of stories. They’re just there for me.

It was great to see the lyrics to so many of your songs in the book. And I especially enjoyed getting to read the original poem that later became “Fourth of July.” I must have read it three or four times. Comparing the end product to the finished song was an exercise in editing.

Dave: I am not the most prolific songwriter, but I am a massive editor. When I write a song, I go through it as if I had 17 editors in my head. Get rid of that. Don't even get rid of that, get rid of that other line. Sometimes songs just flow. They just come out of you and other times you got to squeeze them out, you got to edit them out.

There are times when I will drop that and just let the song blabber on. Sometimes that works, but in general, I am a massive editor. I will write a song and then four years later still be editing it and I will still be editing it even after it's recorded and released.

You talk about this in the introduction. Is a song ever finished?

Dave: Certain songs of mine will never be done. “Border Radio” or something like that, that's edited. Those are the lyrics; that's what's going to happen every time. But there's other songs that are not. Maybe I have a better phrase here, or something pops up five or 10 years after writing the song and you think, ‘That works much better. Let’s do that.’

There was a famous musician (Todd Rundgren), who was in discussions for producing the X album that had 4th of July on it. He said, ‘Well, that's a really good song, but there needs to be more to it.’ I just thought, ‘No, there doesn't. What else are you going to put in there?’

I could put all the other stuff that's in the poem. I could certainly write another couple of verses, but why? That one in particular was finished when I wrote the song. When the music came to me and I started working on the song, it was really just a matter of getting rid of things. In a poem you could be a little more verbose about things, go into more description and all of that. In the song itself, it was just like, ‘Let's just get it down to the nitty-gritty, to the nub.’ For lack of a better term, the who, what, and why.

Toward the end of New Highway is an essay that includes Alvin’s 1999 interview Buck Owens. He also writes an introduction setting the stage for the interview, which memorably includes a warning/veiled threat from Owens’ manager not to mention Don Rich. (Rich, who was Owens’ bandmate and best friend, was killed in a 1974 motorcycle accident. He was just 32.)

One of the best pieces of the book, for me, was reading your interview with Buck Owens for Mix magazine and the introduction, which is new. He had stacks of $20 bills on his desk in front of him, apparently to intimidate you. That sounds like fun.

Dave: It was scary. (Laughs) But it was a lot of fun once I got over my fear.

Why did you write a new introduction to the interview?

Dave: They just kind of put on a generic introduction so I wrote a new one and let people know what it was like. When he was alive, I don't think I would have felt right talking about the stacks of $20s on the table (Laughs). God knows what that was about.

Dave Alvin performing with his brother Phil at The Birchmere in Alexandria, Va., in 2014.

When I read the part about Don Rich and how Owens would cut the interview short if you asked him about it, I couldn't help but think about all the years you had to answer questions about your brother Phil. Is asking about him here OK?

Dave: Paul McCartney is always going to have to answer questions about John Lennon. As far as drags of this sort when you’re making a living this way, those are very small drags. Phil is fine. We’re good.

Again, I really enjoyed the book about your experiences and about people that have influenced you. As somebody who admired you from afar, even though we’ve met a couple of times that one of us remembers, I just want to let you know how much I appreciate it.

Dave: Oh, thank you very, very much, you've made my day.

Written for Americana Highways. To see additional outtakes from this interview, click on the box below.

Impressive interview (and stunning photos), Glenn! I've really only heard of Dave, but was never drawn to his past musical projects....unlike Todd Rundgren's, whose career (musical output and productions) I'm intimately familiar with! I chuckled when I read Dave's account of Todd wanting "more" out of "4th of July"!

I'd never heard it, but am listening to it now and for my money, it's far more accessible than what X was doing a decade before (which I never cared for)....what Todd might have wanted is beyond me, unless it was a bank of keyboards!

Todd was taking a break in his solo recording at the time (1987), and his proggy Utopia band had stopped being active a couple years previous. I'm wondering what had attracted Dave and band to Todd in the first place, unless it was to catch his rising production star...by this time, he'd already produced hit albums by Meatloaf ("Bat"), Hall and Oates, and in '86, XTC's "Skylarking."

Anyhoo, great job, as usual, and it was great to finally get to know Dave thru your interview, and I might forage a bit, now, thru his musical canon!

I'm not familiar with Dave Alvin but your interview makes me want to listen to his music. Well done.