My First Interview

Almost 50 years ago, I got the first taste of my future career: Talking to a child survivor of the worst industrial disaster in U.S. history

In early 1976, I sat in an assistant principal’s office after school, asking about his childhood memories of the deadliest industrial disaster in U.S. history.

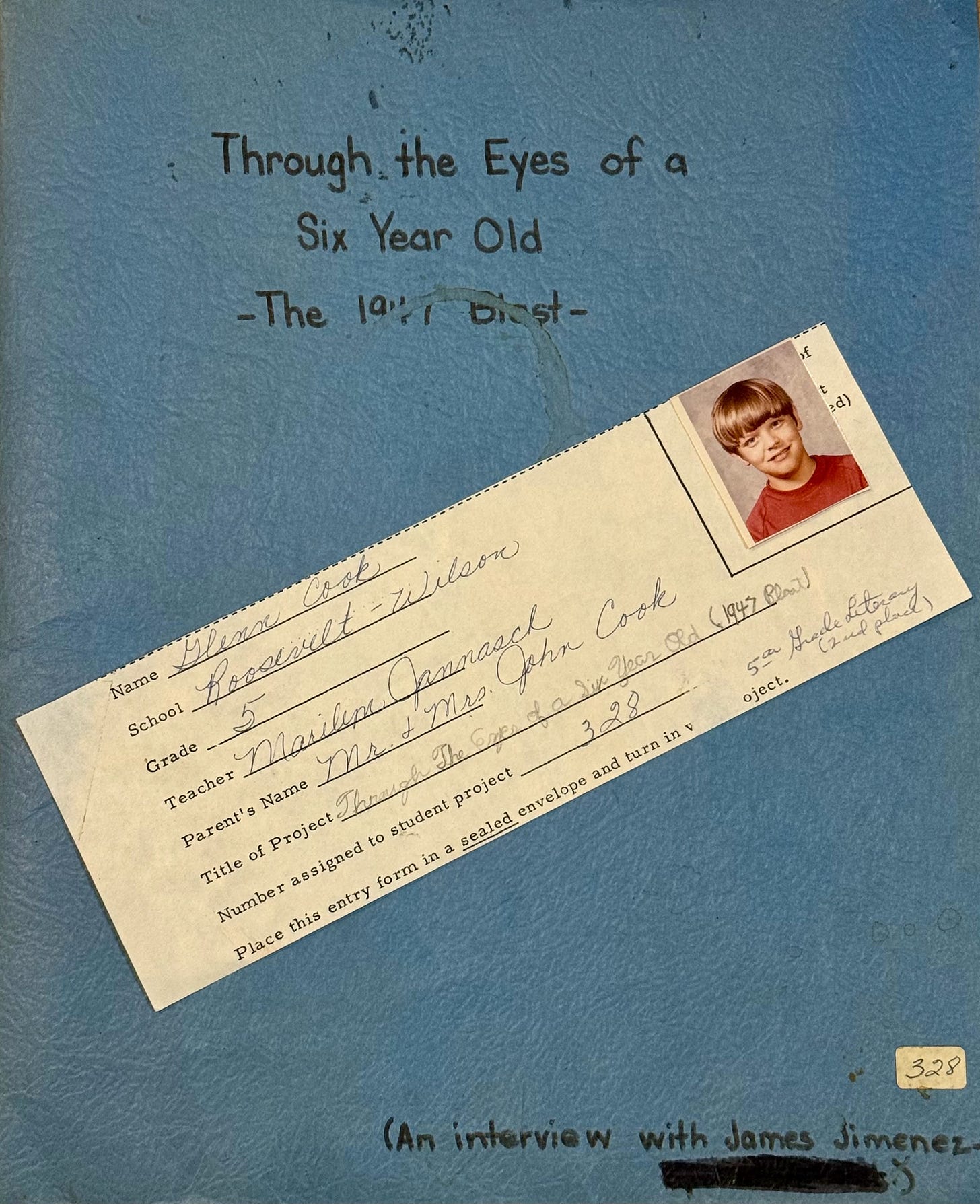

It was my first interview. I was in 5th grade.

The hour-long conversation with Jimmy Jimenez, who lost five family members in the Texas City Disaster on April 16, 1947, was captured on a cassette recorder and transcribed on my grandmother’s typewriter for a countywide Social Studies contest. Recently, while digging through some boxes, I found the light blue folder with the tape, the transcript (titled “Through the Eyes of a 6-Year-old: The 1947 Blast”), and my first “journalism” award — a red Second Place ribbon.

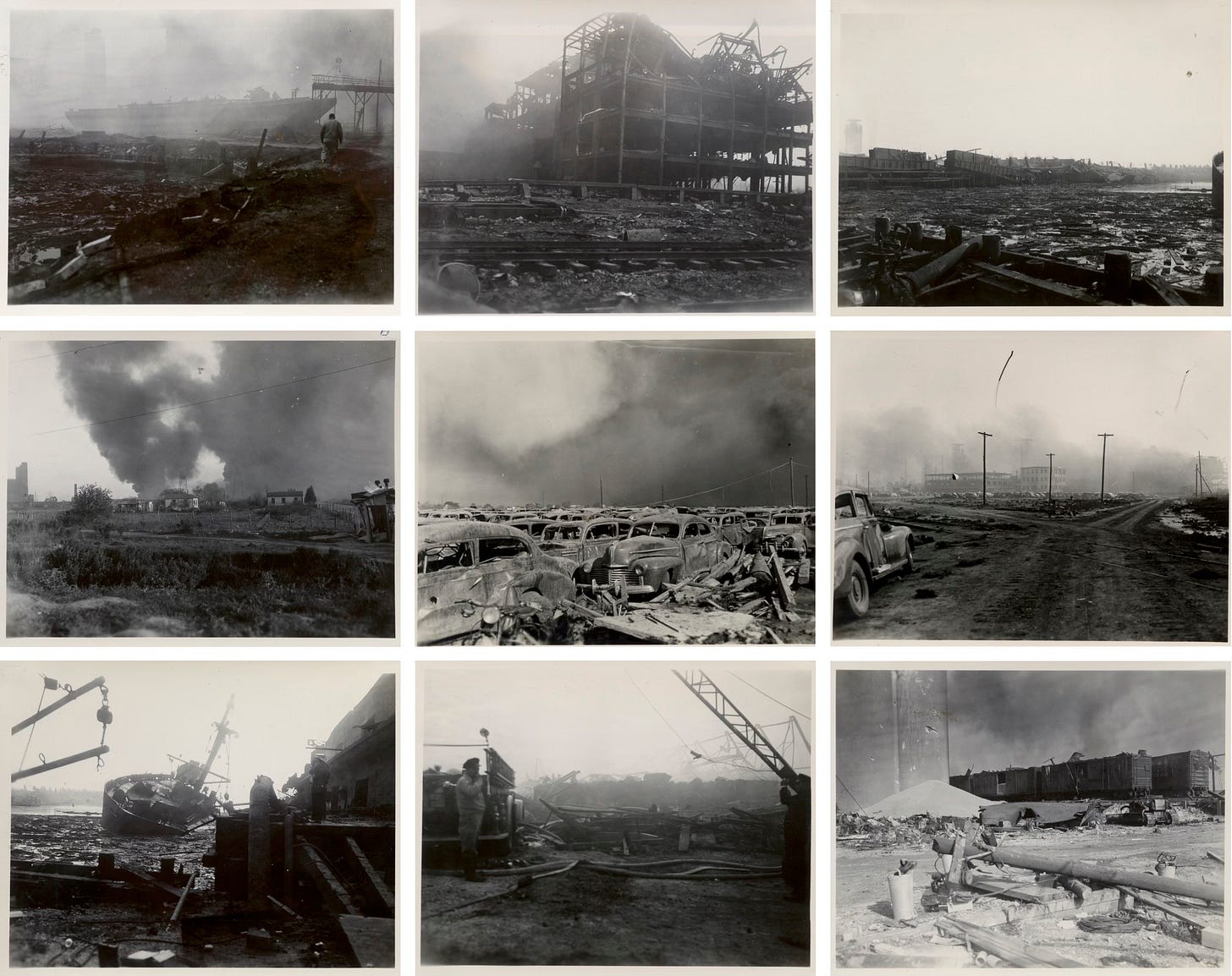

Seventy-eight years after the explosions killed more than 500 people and injured thousands more, I decided to look back at this interview, captured when Jimenez was in his early 30s. What I read and heard was a riveting, visceral, and tragic account of the defining moment in my hometown’s history.

This is Jiminez’s story. I’ve added context in italics to the oral account, which has been lightly condensed and edited.

‘There Was A Big Green Fire’

Texas City is a deepwater port on the southwest shoreline of Galveston Bay, located about 45 miles south of downtown Houston. It is one of the leading producers of petroleum and petrochemicals in the nation and its port is the eighth largest in the U.S.

In 1947, the town was home to two chemical plants, three oil refineries, the nation’s largest tin smelter, and six oil tank farms. Lured by high paying jobs post-World War II, Texas City’s population had grown from 5,687 residents to about 16,000. In the 1940s, houses near the docks were largely owned by Hispanic families who had immigrated to the Gulf Coast town.

About 8 a.m. on April 16, ammonium nitrate fertilizer caught fire in the cargo hold of the French-owned SS Grandcamp, which also was carrying small-arms ammunition, machinery and bales of twine.

Jimenez and his brother, 7-year-old Hector, were morning students at Danforth Elementary because the fast-growing system was at capacity in its primary schools. Three of their six older siblings — two brothers and a sister — went to the school in the afternoon. The Jimenez family lived near the dock and the young boys noticed the fire.

“We heard the fire engines going and looked across at it. I guess we lived a block or two from where the ship was docked. My daddy had built something like a little farm there with cows and chickens and horses and pigs. At the time my grandfather, my mother's father, lived with us. He was a retired railroad man.

My daddy had gotten hurt the week before at work and had a broken collarbone, so he was at home sick. Behind the house there was a pathway cutting from left to right going towards the ship. Hector and I went out that way and followed the path down to where the ship was burning. There was a big green fire going way up above the ship. It looked like copper wire burning.

We saw one of my uncles (Jesus DeLeon). I held his left hand, and my brother held his right hand. We were about 3 to 5 yards from the ship. We stepped over the hoses and there were firemen all around. There were a great number of people there watching. Of course, they had fires down there all the time, so it was a very common practice just to go down and watch.

About that time someone tapped us on the shoulder. It was my Daddy. He told me and Hector to go and get our books because we were late for school.”

The Explosion

School started at 9 a.m. At 9:12 a.m., the Grandcamp exploded, destroying the entire dock area, Monsanto Chemical Company, grain warehouse, more than 1,000 buildings, and numerous other oil and chemical storage tanks. The concussion from the explosion produced a 15-foot tidal wave, shattered windows in Houston, was felt 250 miles away in Louisiana, and registered on a seismograph in Denver, Colorado.

“Hector and I had gone down the road toward school. We were fixing to cross Texas Avenue when the ship blew up. We didn’t know what happened. We thought the world was ending or something. We went ahead past Texas Avenue and walked about half a block, but we were scared to death.

There was a huge cloud — real, real dark — and you could see things flying in the air.

It was coming from the south and going north, almost blotting out the sky. It reminded us very much of a norther coming in. Hector and I kept on running toward Danforth.

We ran into our brother, Joe, who was in about the ninth grade. We were crying and I grabbed one leg, and Hector grabbed the other leg. We were scared to death.

The first thing he asked us was where were Mom and Dad. I looked back toward the blast area and pointed in that direction. Joe sald for us to go to Danforth, that they were picking up school children on buses, and he took off running toward the house.”

Jimenez said his father and grandfather were standing in their yard watching the fire when the ship exploded.

“My daddy was smoking a cigarette, and they were waiting for my mother to finish breakfast. My older sister Mary was asleep in one of the front bedrooms. When the explosion took place, flying glass from the window where my mother was standing cut her real, real bad.”

Jimenez said his injured mother tried to rush out of the house to check on another sibling, Ernestine, who was working at one of the petrochemical plants nearby. Mary managed to get her mother into an ambulance to go to a hospital in Galveston.

“My dad and grandfather had fallen down in the yard. My dad got up and looked at my grandfather. He had a piece of steel running from the top of his head to below his chin. He was dead. Daddy had his shirt and one shoe blown off.

Daddy took off running inside the house. We had a kerosene stove that had turned over and it was catching fire. There was a bucket of water nearby and he picked it up and put the fire out. He got a big blanket from the closet and took off to where my sister was working. He was one of the first guys there.

He noticed a lot of people dying or in the stages of dying, with limbs cut off. They were asking for help. It was like a nightmare. He went to where my sister Ernestine was working and the building had been leveled, He dug around looking for her and finally found her. She couldn't talk. She was in agony. She was about dead then. It was 10 days before her wedding. She was going to get married to a boy from Baytown.”

Jimenez’s older brother found his grandfather next to a pig stye. He put the body into a wheelbarrow and rolled it to the street where an ambulance picked it up. His grandfather was taken to a makeshift morgue in the old high school gym.

“Meanwhile, my dad was trying to lift my sister. Because of his bad collarbone break and the big cast he couldn't. He saw a man running toward him and asked if he would help carry his daughter. The man said that was why he came. There wasn’t much more exchange of words. They rolled my sister in a blanket and ran a steel pipe through it. With the man's help, they got her to one of the first ambulances. She died on the way to Galveston.

After my father put my sister on the ambulance and my brother had taken care of my grandaddy, my brother found my daddy. They went to City Hall where there was a temporary Rod Cross Station. There were a lot of people coming from everywhere to help.

My dad and my brother spent the night there. They didn't know if we had been killed or not. They were asked to go into the plant area that night, but they decided not to. People were going in to get bodies out and look for people who were injured. They were digging out bodies and about 1 a.m. (on April 17) there was another explosion.”

The High Flyer, another cargo ship loaded with 2,000 tons of sulfur, had been released from its moorings by the force of the Grandcamp explosion. At least two people were killed in the second explosion, which wrecked a third cargo ship, destroyed several nearby grain elevators and what was left of the pier. Meanwhile, Jimmy and Hector were separated from their family.

‘We Just Kept Running’

“Hector and I proceeded toward Danforth like our brother asked us to. We ran into my sister, Josie, who was in the fourth or fifth grade. She grabbed us by the hands, and we ran northward until we got to Loop 197. Then we got on the right side of the loop and just kept running.

It seemed like we were trying to escape from the end of the world. We were so frightened.There were lots and lots of people. It reminded you of refugees leaving a war area. People were panicky, nervous, and crying. We just followed them out to Highway 146 and turned right, going (north). We ran all the way across the old wooden bridge at San Leon. On the other side were a lot of yellow railroad houses. We stayed there for an hour or two.

While we were there, a lady put us in her automobile and took us to Houston. We didn't know her name. We thought our parents were dead. We spent several nights at her place. She lived upstairs in an apartment. Downstairs there was a cafe, a bar or something. I remember the record player playing.

After we were there several days, she took us to Camp Wallace, a deactivated U.S. Army post (in Hitchcock, about 10 miles from Texas City). There were a lot of empty barracks, so the Red Cross set up a temporary station. They brought in food and clothing and while we were there we ran into uncles and aunts and some of our relatives.

We found out our parents were alive. For two weeks, we had not known. My mother had been in the hospital about a week or so. She didn't know who had died or anything. The reports being sent out included my dad’s name in the list of the dead, even though he wasn't. Relatives couldn't find out anything.

Several days passed and we found out my grandfather, my sister, and the uncle that we watched the fire with were killed. Two cousins who went to school in the afternoon were watching the fire and they were killed. All five of my relatives are buried side by side at the cemetery.”

The Aftermath

It is unknown how many people died in the explosions, with estimates ranging from 500 to 600. The ship’s anchor monument lists 576 deaths — 398 were identified and 178 were listed as missing.

Memorial services were held on April 19 at the high school football stadium and on May 30 at the fire station to honor the 28 firefighters who were killed in the first explosion. On June 22, an interdenominational funeral service was held for the victims whose remains could not be identified.

After the funeral they set up temporary housing near where Food Giant was. We stayed there until we could rent a place in Galveston, We went to school in Galveston, and then, after things were getting back to normal, we moved back to Texas City.

We didn't feel the impact as much as my father because we were so young. It was a nightmarish, scary, horrible thing. From being very calm to being chaotic — no home, no job — it really hurt him so much.

My daddy and mother were crushed. They cried a lot. It was a nightmare. The aftermath was like hopelessness. It took so long to accept the fact that so many relatives were killed.

The city slowly recovered, even though officials say the emotional effects of the blast is still felt by families today, almost 80 years later. In the immediate aftermath, fundraisers featuring celebrities Jack Benny and Frank Sinatra, among others, helped raise much needed money for the victims’ families. Monsanto rebuilt its refinery, as did other petroleum and petrochemical companies.

The Texas City Disaster is cited as the source for large scale disaster planning in the U.S. New standards were put in place for the storage, transportation, and dispersal of ammonium nitrate. In 1955, eight years after the blast, $17 million was allocated by the federal government to be distributed to 1,400 people.

Jimenez and his brother, Hector, were teachers, coaches, and administrators in Texas City throughout my years in school. Hector died of a heart attack in 1995 at age 54; Jimmy, now in his 80s, still lives in Texas City.

To learn more about the Texas City Disaster, visit the Moore Memorial Public Library’s website here.

Glenn, what a wonderful interview. I heard these stories my whole childhood. My mom was 8 months pregnant and down the street at CB Shelton’s. They were going to go down and watch the fire but CB hadn’t finished her breakfast dishes. My dad was delivering a load of lumber and got a cut on his ear when the blast blew out the windows. My grandfather had just left the little diner down there and was walking back to Republic Oil. He was knocked down and lost his glasses. My grandmother was the police dispatcher and was on duty. The fact that I had all four direct family members affected, but none severely injured or killed is a miracle.

What a prodigy! Now we know where that young achievement gene(s) come from in your family!