No Happy Endings

Almost 30 years after O.J. Simpson’s murder trial, a nation remains divided

On June 17, 1994, I was sitting in a strip mall sports bar with my former boss in Texas City, watching the Houston Rockets take on the New York Knicks in the NBA finals. The series was tied 2-2, and it featured enough personal intrigue and history that even a casual NBA fan like me was interested and invested in the outcome.

Hakeem Olajuwon and Patrick Ewing were facing each other, just as they had when Ewing’s Georgetown Hoyas defeated the University of Houston (my alma mater) in the 1985 NCAA championship. This was the Rockets’ best chance at a title; Michael Jordan had “retired” and was playing AA baseball at the time, even though he would return to the court late in the 1995 season.

Would the Rockets succumb and continue the seemingly never-ending jinx that affected Houston’s college and professional sports teams? For a Houston area native who had watched the Oilers, Astros and UH teams flail and fail on multiple occasion during crunch time, I was pessimistic.

At the time, the game was secondary to the conversation with John Simsen, who was the managing editor at the Texas City Sun. I had come home to visit family a year after moving to work in the same role in Reidsville, N.C., and our meeting was a good opportunity to catch up and talk about the myriad challenges involved in running the editorial side of small community newspapers.

In those days, almost 30 years ago, TVs in bars weren’t the large flat screen behemoths you see today. The game became very small when the screen was split and the shot of the white Ford Bronco appeared on the right half. And no one could see the armed fugitive hiding in the back seat as Tom Brokaw broke in to narrate what viewers were witnessing.

The Dramatic Story

As a child, one of my favorite things was to order from a list of Scholastic paperbacks during the periodic fundraisers that came through my elementary school. Despite my love for learning about the presidents, by the time I was in fourth grade, most of the books were about my newest obsession: football.

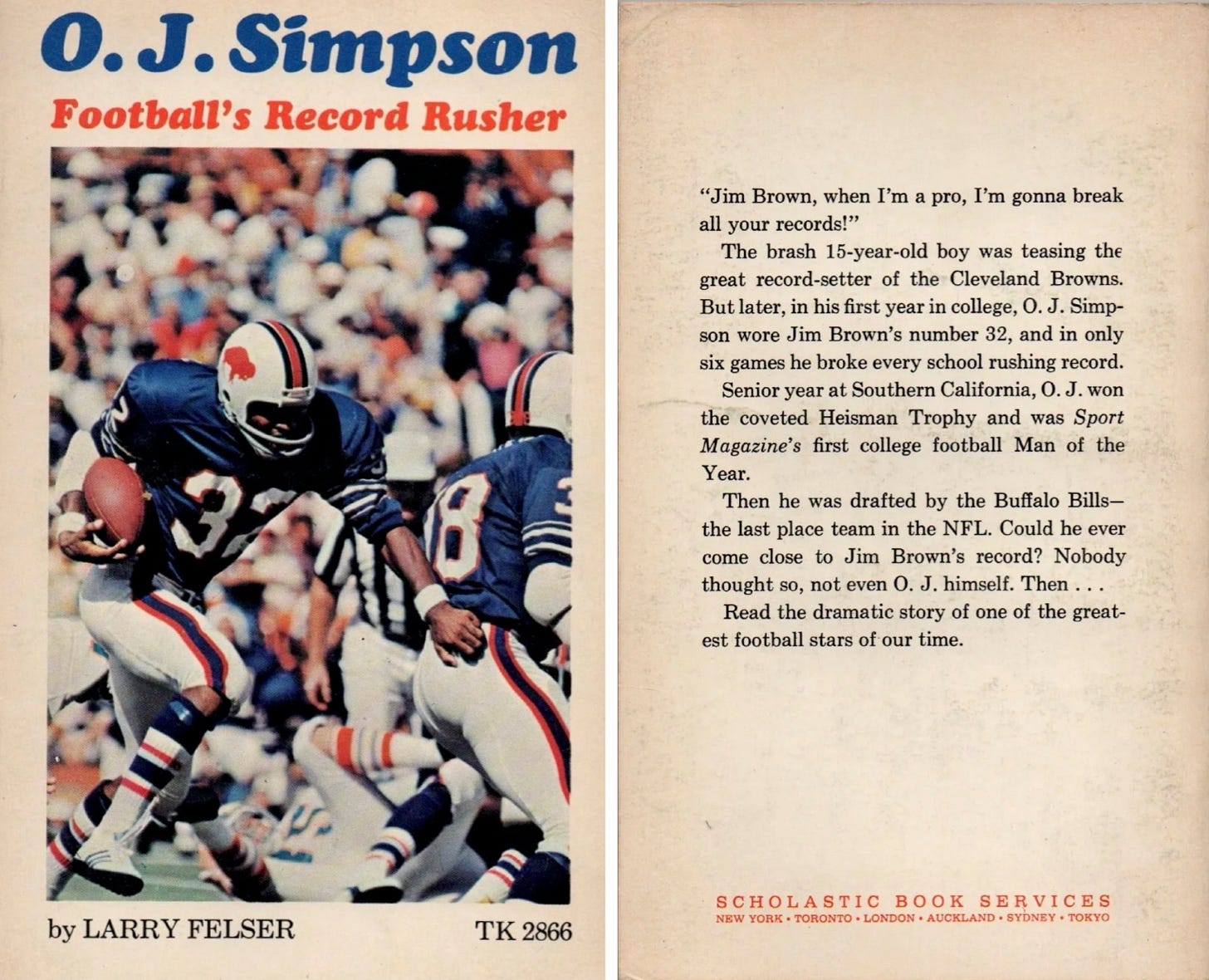

In 1974, at age 9, I vividly remember getting O.J. Simpson: Football’s Record Rusher, in a Scholastic sale at my elementary school. The 92-page biography was written quickly by Larry Felser, a longtime NFL reporter and columnist for the Buffalo News, after Simpson became the first to break 2,000 yards rushing in a single season.

Felser covers Simpson’s story to that point in 13 concise chapters, starting with “The Boast” — the running back’s pledge as a 15-year-old to break all of Jim Brown’s records. It then hits the sanitized highlights and challenges of Simpson’s life — his childhood battle with rickets that forced him to wear steel braces on his legs; the Heisman Trophy at University of Southern California (wearing Brown’s number 32, no less); the hardships caused by moving to frigid Buffalo and to a losing team; and the quest for 2,000 yards earned during the final game of the 1973 season.

I can’t tell you how many times I devoured that book in fourth and fifth grade, thinking at the time that its back cover exhorting me to read “the dramatic story of one of the greatest football stars of our time” was completely accurate.

I had no idea how dramatic O.J.’s story would become.

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Simpson seemingly was everywhere. He was a pitchman for Hertz, a not-so-great commentator on NFL games, and a “name” actor in mostly bad movies. He married for a second time to Nicole Brown, a beautiful blonde he met soon before was divorced from his first wife. The two seemed to have everything, including two children to go with the three from Simpson’s previous marriage to his childhood sweetheart.

But the marriage had a dark side. Domestic violence calls went unheeded, or were dismissed, even after the couple separated and then divorced. After all, this was O.J., an American hero, a person who in his own words, transcended race in a city where police brutality against Blacks was legion.

The Deep Divide

As the white Ford Bronco, driven by O.J.’s longtime friend Al Cowlings, maneuvered its way down the 405, patrons urged the bartender to turn the sound up. The basketball game became secondary. At some point the conversation did too, as we watched the footage of the slow-speed chase that ended with police surrounding Simpson’s Brentwood home.

John and I looked at each other and shook our heads, glad we weren’t sitting at our respective city desks waiting to see how this would turn out. We left the bar after the game — a 91-84 Knicks victory that gave New York a 3-2 series lead — wondering what kind of crazy thing would transpire next.

Remarkably, Olajuwon led the Rockets to two wins at home to win the Rockets’ first major professional championship. He would help them win a second before Jordan returned to the NBA and continued his dominance over the league.

But that was a distant second compared to what was taking place in Los Angeles, where Simpson — so admired and feared as a runner — was facing a double murder charge that would divide our nation in ways we did not realize.

The televised trial — and the not guilty verdict — transfixed the nation. Everyone had an opinion, with a majority of white Americans believing O.J. did it and an equal number of Blacks feeling he did not. In Los Angeles, the community where white officers had been caught on video severely beating Rodney King three years earlier, the divide was even greater.

After the news of Simpson’s death was announced today, I spoke with my friend Ed, who was a student at Georgetown Law School at the time. Ed, who is Black, called Simpson’s trial a “Rorschach test for me.” He noted that all of the legal evidence “seemed like O.J. did it, and I believed if he did it, he shouldn’t get off Scott free.”

But the reaction of his white colleagues to the trial — “the nastiness and viciousness I saw” — based on Simpson’s race completely changed Ed’s mind. When the verdict came down, he was “completely glad that Johnny Cochrane got him off.”

“He had a good lawyer, and he did what any rich person — white, Black, or indifferent would do,” Ed told me. “I was really angry at the reaction of the white folks, the supposedly educated folks, that I was in law school with at the time. I felt naïve. I thought, ‘If the reaction is what it is here, imagine what it is elsewhere’.”

The Oscar-winning documentary, “O.J.: Made in America,” illustrates those conflicting emotions between whites and Blacks in deep and powerful ways. Almost 30 years later, the racial divide over our judicial system remains deep, along with many other subdivides that leave us more fractured as a nation than ever.

O.J.’s life and death have been compared today to a Shakespearean tragedy — the story of the dramatic rise followed by the equally dramatic and destructive fall. It is a cautionary tale for anyone who earns or somehow falls into sudden fame and doesn’t know how to deal with the inevitable lulls and valleys that follow.

A sad outcome in this tragic story is Simpson never took accountability for his actions and continued in his quest for another moment in the sun. What followed was a series of mini-tragedies — the civil verdict on behalf of the murder victims that was never paid in full; the nine years Simpson served in prison after a botched robbery attempt in Las Vegas; and how the “Trial of the Century” only amplified and accelerated our nation’s lust for more lurid true crime stories.

This is a story that, while dramatic, will never appear in a Scholastic book. It is one without any happy endings.

Wow excellent piece of writing, I really enjoyed reading it from an Australian perspective so we really only saw the media portrayed , thank you for sharing the story

Great piece, Glenn. The personal and the political and the sensational all overlapping and informing each other. I can’t believe that was 30 years ago.