One Piece at a Time

Keeping the faith can be tough at times, especially near the end of life

“The story of our lives. Written page by page. Oh be careful what you write. You gotta read it all someday” — Jon Dee Graham

When I was a child staying with my grandmother in East Texas, inevitably I had to take food to Mrs. Douglass’ house.

I viewed this as penance for some yet-to-be-committed sin, in part because Mrs. Douglass and I had nothing in common and I was not interested in a career in the pharmaceutical industry at age 11. At this point in the story — Mrs. Douglass was a white haired, frail widow in her early 80s — conversation revolved around her various doctors’ appointments and the prescriptions she was taking.

Mrs. Douglass was inevitably polite — although bitter about her lot in life, it seemed to my childhood self — and she always seemed to enjoy my visits. The pattern rarely deviated: I sat on the couch and, after a 30-second description and acknowledgment of the home-cooked meal my grandmother had made, listened to her describe her various ailments and what they prevented her from doing. After 15 or 20 minutes, I was escorted to the door and told to come back soon.

“I never want to be like that,” I told my grandmother more than once.

She nodded, pursed her lips slightly, and gave me a half smile.

“You can give away some things. That you never will get back. One piece at a time. And you never will get them back.”

My father-in-law died nine years ago last month. I knew him for the last two decades of his life, a period in which his conversational window narrowed considerably. At one point we could talk about photography; by the end he barely looked at the pictures I showed him, even though they were of his grandchildren. For most of his life, he could provide you with a dissertation examining the merits vs. the weaknesses of any sport involving the University of North Carolina. Toward the end, he rarely spoke about his beloved Tar Heels.

The relationship Jill had with her father was fractious, prickly, and tense, dating back to her childhood. When Bob was alive, she spent countless hours trying to figure out the enigma who was 50 percent responsible for her place on this planet. She learned not to mistake duty for kindness.

Like Mrs. Douglass, the end of Bob’s life revolved around two things — his visits to the doctor and the various prescriptions he took to extend his life. He was bitter, so focused on those things that he didn’t seem to care about much else.

In the fall of 2011, less than 18 months before Bob died, I drove to Boone as part of a Virginia/North Carolina trek that I made frequently when my son Nicholas was growing up and in college. It was an opportunity to help Jill and her brother, Michael, who were trying to see Bob at least once a month.

Bob said he appreciated my taking him to the doctor and taking care of the things he had on a never-ending list. He talked of wanting to leave the assisted care facility to return to his house full time, although he’s wasn’t in good enough health for that to happen.

His charm with others not close to him remained intact. The person who cut his hair for years spoke of his wit (and his love for Carolina sports). As he shuffled through the lobby, where a community band honked through the “Gilligan’s Island” theme at a 5:30 dinner concert, a couple of his fellow residents perked up, said hello, and waited for his acknowledgment. He gave them a nod but didn’t sit with them.

Meanwhile, his temper simmered just below the surface, and he struggled not to bark or bellow. His temper, while infamous, was not something his children talked about, and you could see the struggle to control it. When I left, I felt uneasy about the interaction even though I had done “my duty.”

On more than one occasion, I heard Jill mention that her father was not a kind man. I didn’t understand it fully, however, until that visit, when I realized all along that I had mistaken gratitude for late in life kindness I hoped to see.

“You need a strong heart. You need a true heart. You need a heart like that in a world like this. So you don’t get faithless.”

On Sept. 11, 2007, my second “mom” passed away. In many ways, she had died 3 1/2 years earlier.

Growing up I said I had two sets of “parents” — my biological ones and Fran and Bill, who lived across the street from us. We moved into my childhood home on 22nd Avenue in Texas City when I was 4, and my parents became fast friends with the couple across the street and one house over to the left.

Much more than my parents, Bill was my personal familial enigma, although unlike Bob we reached a much more peaceful resolution in the end. As a kid, with my mom facing a much more difficult juggling act (work, kids, sick husband) than any of us knew, I often turned to Fran for advice and support.

And Fran freely dispensed it, in what my mom called her “Yankee” way. (It took me a while to realize that mom’s definition of Yankee included the south side of Chicago.) Fran was always quick with an opinion and never afraid to share it, but ultimately she was always supportive and quick to call me her “son.”

Like my father, Fran had health issues for much of her adult life, and it took me some time to realize just how much she relied on Bill for everything. Without children of their own, all they had was each other, even though they treated us like their kids.

Fran marched in lock step with her Catholicism, never missing a mass and politically aligned largely with its beliefs. But after Bill died in 2004, she started questioning everything, including her own belief about the end of life.

One afternoon, during one of my 14 trips to Texas in 2007 to see my dad in the hospital, I stopped by Fran’s house for a visit. She was using oxygen, largely confined to bed or her chair.

Like Bob and Mrs. Douglass, most visits with Fran at the time were conversations about doctors, her various caregivers, and her medical treatments. The conversations had narrowed so much that a person I once could talk to at any time ran out of things to say in just minutes.

But on this day in mid-May, we sat in her bedroom, went through pictures of the kids — unlike Bob, she remained interested — and talked about the trivial things. It was just like the old days, and she even endured a song I could not get out of my head — Jon Dee Graham’s “Faithless.”

She put her head back on her chair and listened, eyes closed.

“In the deep blue dark down under. Tell me what you’re thinking of…”

Fran smiled.

“The things we find. The things we lose. The things that we get to keep. Are so damn few. And far between. So far between…”

She teared up but rebounded at the conclusion.

“You need a strong heart. You need a true heart. You need a heart like that in a world like this. So you don’t get faithless.”

For a moment, she seemed more confident. “That’s how I feel on so many days,” she said. “I get so frustrated. It’s so easy to do.”

Fran told me how much she enjoyed the visit; I thanked her and mentioned how much she meant to me. I gave her a kiss and let myself out as she sat in the chair. In less than four months, just six weeks after my father died, she slipped away too.

“I AM NOT FAITHLESS.”

To read my 2019 interview with Jon Dee Graham, go to “The Music Diaries” section of this site or click on the link below.

Finally, The Daily Photos

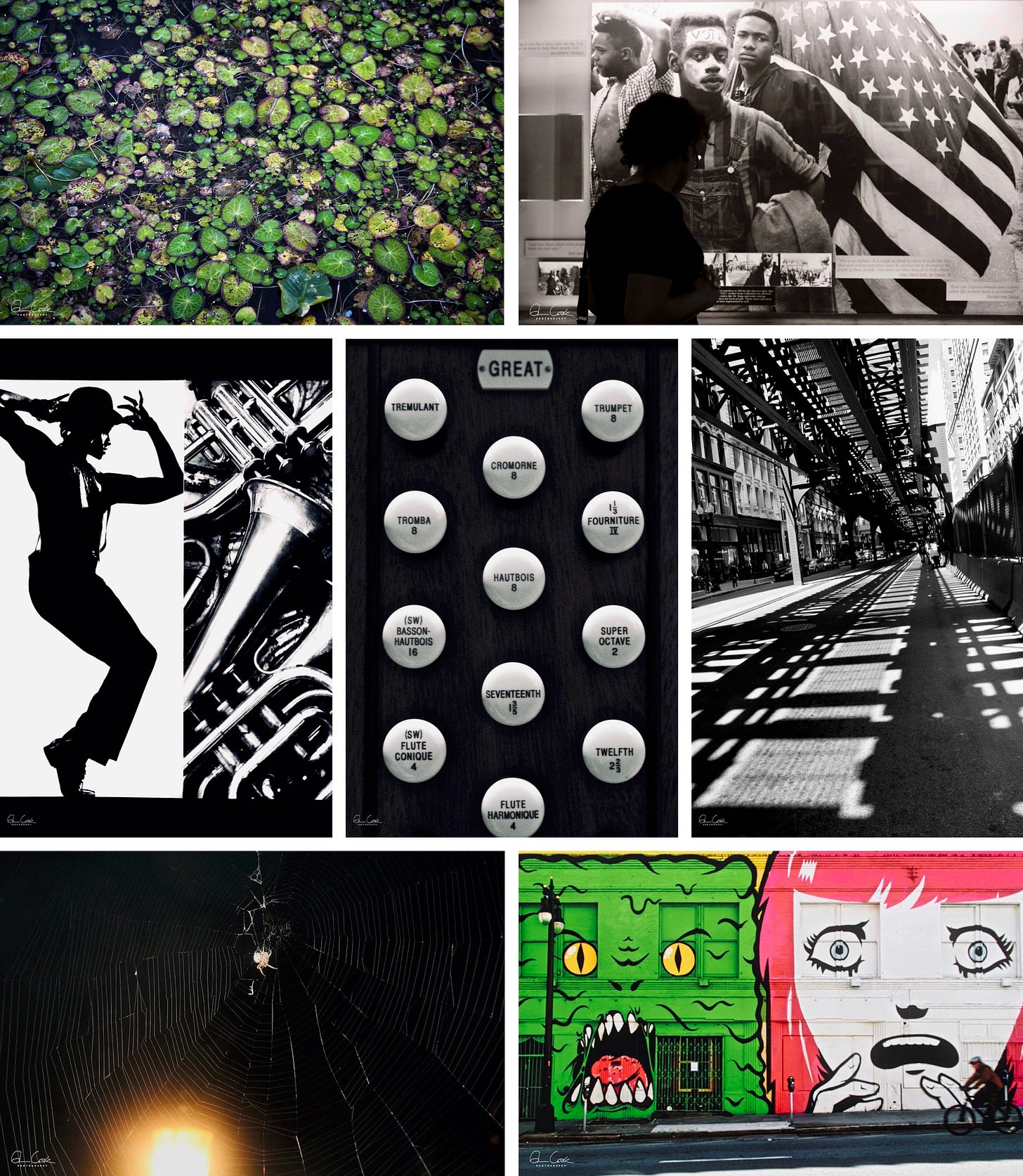

Here are the Daily Photos posted for the week of March 7-13 to my Facebook business page. The photos represent the random things captured during travels to various places. If you’re on Facebook, you can check out the full-size images there. If not, you can view my page by going to this link. (You don’t have to be on Facebook to see my page.)

If you have any questions or are interested in purchasing a print, let me know in the comments or by sending an email.

Thanks as always for visiting, and have a great week!

You have such a gift for painting vignettes with your words. Powerful storytelling. Thanks for this.

A different portrait of Bob. I am so amazed that the “simmering” wasn’t observed by me in next door contacts. I loved Betty and the children and triuthfully had most of my interactions with Jill and her Momma. Give Jill a. Hug from me and tell her I wish I had given her even more!