Places: New London, Texas

Small East Texas town is the site of the nation’s deadliest school disaster

Note: One of my goals as a parent has been to take each of my adult children to East Texas to see where my parents grew up. Five years ago, Nicholas visited Longview and Kilgore. Last month, I took Ben on a similar journey that also included a stop in New London, a small town in Rusk County.

This is the third in a series of visual stories on the three towns, all greatly impacted by the Texas oil boom and full of stories — some personal, some societal. Click on the links at the bottom of this entry to read the stories on Kilgore and Longview.

Eighty-five years ago, an underground natural gas explosion at a school in a tiny East Texas town killed more than 300 people. But unless you live in the area or are a history buff, chances are the deadliest disaster in K-12 education history is little more than a footnote.

My maternal grandfather, who was just 24 at the time, was one of the first responders to the London School in Rusk County, Texas, following the explosion on March 18, 1937. A.T. Vestal was building refineries for Premier Oil Company when he got the call. He was shocked by the mass of rubble he found; the carnage, he later told my mom, was as bad as anything he saw in Okinawa during World War II.

Also there that day: Walter Cronkite, a fellow Texan working at the time for United Press International. During an interview I did with him for the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education in early 2004, he described the London School explosion as “the day a generation died.”

The subject came up when I mentioned to Cronkite that I started my first journalism job at 18 in my hometown. He asked about my first “big story” — it was covering the Challenger memorial service at Johnson Space Center just after I turned 21 — and he told me he was just 20 when he was sent to New London, Texas.

“It was terrible,” he said. “I had never seen anything like it.”

I filed the quote away, then found it again when I started writing a feature on New London for American School Board Journal (ASBJ) in early 2008. At the time, it had been 70 years since this horrific disaster, and I wanted to know why it was not better known. Ironically, I didn’t know the story about my grandfather’s role as a first responder until after the feature was done and I mentioned it to my mom.

Unlike his youngest grandson, my grandfather was not much of a storyteller. But he described arriving at the scene, looking for someone to help in the rubble, and hearing a voice from above. A child survivor was hanging by his overalls from the shreds of a metal beam, asking for help to get down.

Survivor stories

By all accounts, it never should have happened. What ASBJ described in an April 1937 editorial as “the most distressing disaster in the history of American school life,” took place in a county that had the largest oil field in North America at the peak of the Texas oil boom.

When the school was built in 1932 to serve junior high and high school students, New London officials bragged that they had the world’s richest school district, even though oil workers from out of state lived with their families in tents.

The school district still cut corners, substituting natural gas for steam heat they could tie into a free line that used gas residue from the oil fields. The gas was odorless, and a teacher did not smell the leak in the basement when he turned on a sanding machine. The mixture of gas and air exploded, lifting the school off its foundation.

Jimmie Robinson, then in third grade, had walked over to the school “to see the Mexican hat dancers” at a PTA-sponsored event. She was buried in the rubble, with a half-dollar sized hole in her forehead. Her sister Elsie, three years older and injured herself, refused to leave until Jimmie was out.

“I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for her,” Robinson told me in 2008. “They took me to the hospital, cleaned the dirt out of the hole in my forehead, and said if I lived 24 hours I might make it.”

The body count was staggering. Initial reports ranged from 250 to 500 killed. Today, the number is still not known; the best estimate is 319 dead.

“At that time, this was such a transient area,” said Miles Toler, a New London native and 1958 graduate who ran the London Museum until his retirement. “A lot of them found their kids, had their bodies put in a casket, and went back to Oklahoma or Arkansas and buried them. We still don’t know how many kids died.”

Robinson’s family moved to Houston. “It was hard times for families right after the Depression,” she says. “People were just recovering. They had such a tough life and that was just one more blow, so after it was over with, they scattered. They didn’t want to stay there.”

Joan Barton and her husband, Gerald, both lost siblings in the blast. Barton, who was in second grade at the time, left New London after graduating in 1948, but moved back to the area in 1982 and worked as a museum volunteer. When I interviewed Barton, who died in 2012, she said the explosion was still difficult to discuss.

“We weren’t allowed to talk about it. We were not allowed to talk about it at all,” said Barton, whose lost another sister in 1939 from lupus that she contracted after the explosion. “It was just too sad. I still can’t talk about it without crying.”

Telling stories

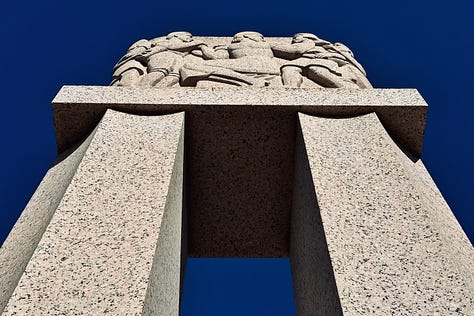

Across the nation, schoolchildren donated $20,000 to build a 32-foot granite monument honoring the dead. The cenotaph—Greek for “empty tomb”—stands today on state Highway 42 between West Rusk High School and the museum.

In the wake of the New London explosion, families filed more than 90 lawsuits against the school district and the Paradise Gasoline Company, “trying to blame somebody,” Toler said. Superintendent W.C. Shaw, who lost a son in the explosion, was forced to resign. Ultimately, a Court of Inquiry found no individuals responsible, saying school officials were “ignorant or indifferent to the need for precautionary measures, where they cannot, in their lack of knowledge, visualize a danger or a hazard.”

For decades, the explosion hovered over New London. Survivors did not discuss it. They grieved lost siblings and friends, wondering why they lived when others did not.

“There were just a few little preachers and the good Lord to take care of you, and that was it,” Toler told me in 2008. “There was no outpouring of emotions. People just kept it inside and didn’t talk about it for 40 years.”

In 1977, the first reunion associated with the disaster was held. In 1992, former Mayor Mollie Ward helped form the organization that runs the museum, which has a volunteer staff of 25 to 30 who conduct tours and tell the story of the explosion and the aftermath. Still photographs from the 1930s adorn the walls; after 85 years, only a handful of survivors remain.

New London is the third-deadliest disaster in the history of Texas after the Galveston Hurricane of 1900 and the 1947 Texas City Disaster. More information is available at http://nlse.net.

Note: Below are videos published by the Longview News-Journal to commemorate the 85th anniversary.