Putting Faith into Action

How civic virtue played a large role in the battle to desegregate K-12 schools

This piece was written by Cecile S. Holmes, former religion editor at the Houston Chronicle and then a professor at the University of South Carolina’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications. Cecile and I worked together with her students on a series of stories about Briggs v. Elliott, the first of the five cases that led to Brown v. Board of Education.

A longer version of this article, which looks at the role of civic virtue in the fight against school segregation, appeared in the April 2004 edition of American School Board Journal. It appeared as a compliment to my story on Summerton — “From First to Footnote.”

By CECILE S. HOLMES

It was the late 1940s, the era of Jim Crow, and a time when black families sometimes had to travel miles just to find a "colored" bathroom. For African Americans, life in all aspects of society was separate and decidedly unequal.

Yet that reality did not deter a small group of South Carolina parents who wanted the best for their kids. Something deep inside, something almost unknown, stirred them to pursue justice and equality for their children.

This civic sensibility puts them in good company, even though some of their companions seem strange bedfellows for a group of small-town folk who challenged the racial mores of their time.

From John Winthrop to James Madison and Thomas Jefferson to Martin Luther King Jr., there is a long tradition in American history that favors civic virtue — putting one's faith into action for the greater good. Throughout U.S. history, the principle that faith should call forth worthy behavior has been at work. What varies is the action.

'Sacred Opportunity'

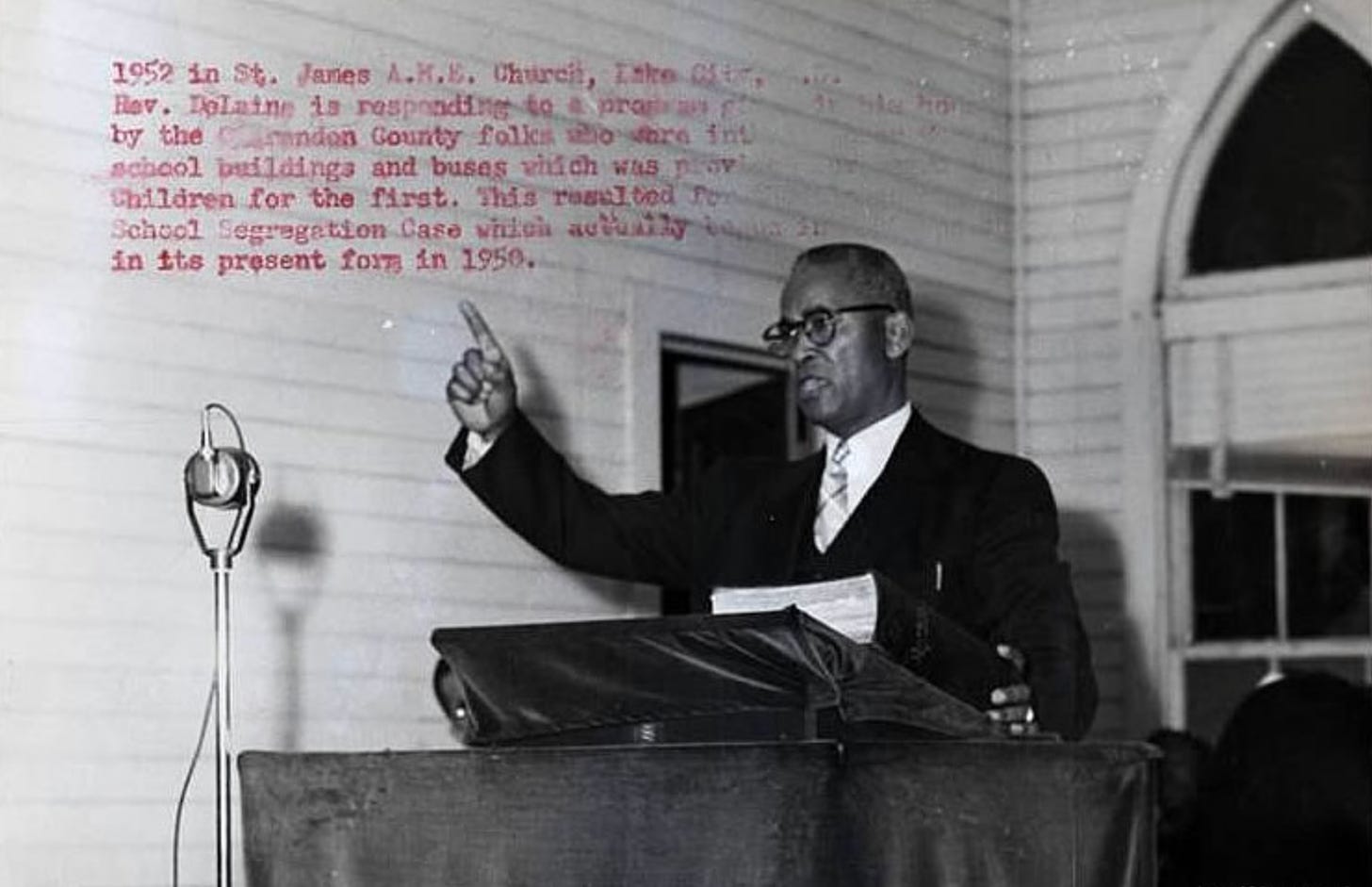

In a sermon entitled, "Go Forward," the Rev. J.A. DeLaine Sr. preached that each man, woman, and child is born into a life of "sacred opportunity." For DeLaine, educational inequalities in Clarendon County, S.C., represented that opportunity and the chance to make a difference.

By the late 1940s, he championed the cause of the 20 plaintiffs who challenged the separate but equal doctrine than had doomed their children to substandard treatment in the Clarendon County schools. The black parents' initial request to a white school board was simple enough: They wanted bus to carry their children to school. They also sought dated books, qualified educators, and better school buildings.

DeLaine, a teacher/principal at one of the county's black schools and pastor of a local church, persuaded the parent to initiate a legal battle. Over a five-year period from 1949 to 1954. as Briggs v. Elliott slowly wound its way through the courts. DeLaine helped hold the plaintiffs together despite intense personal and professional pressure. But he never stopped trying to make the most of his "opportunity."

Civic virtue can be found in each of the five cases, including Briggs, that ultimately led to Brown v. Board of Education. What is largely not reported, and often unrecognized, is the role of the ministers — DeLaine. the Rev. Oliver Brown of Topeka, Kan., and the Rev. L. Francis Griffin of Prince Edward County, Va. — in three of the cases. Yet their activism, fearlessness, and determination are often cited as keys in encouraging poor, wary black parents not to give up the fight.

All of these characteristics can be found in DeLaine's papers, which are housed at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. ("He kept everything. He wrote everything down and kept it," son Brumit says.) This is especially true in his sermons, which show an uncommon dedication to a cause so unpopular in the segregated South that few believed it would succeed.

"Every man, woman, or child will eventually give their allegiance to some cause, force, or movement," DeLaine wrote in one powerful sermon. "Every man's allegiance will be a factor in determining the future progress, success and happyness [sic] of his home, community, state, or nation. The vast majority of mankind is not concerned, as he should be, with the effect his influence bears upon the progress of human society. But every man has a contribution he should make."

Why They Pay The Price

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. literally gave his life in making such a contribution. The Rev. J.A. DeLaine gave all but his life.

Leading the charge to end separate but equal cost DeLaine his home, which was burned while firefighters watched, damaged his successful career in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, helped ruin his health, and destroyed his peace of mind. But he refused to retreat.

"Is this the price free men must pay in a free country for wanting their children trained as capable and respectable American citizens?" he argued in a statement responding to harassment by white segregationists in 1949.

This level of dedication makes sense if it is understood as flowing from the historical American stream that stresses that every person of faith must give to the wider community. Since the 1700s, many of our nation's leaders have preached a similar message.

In his inaugural address to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Puritan John Winthrop spoke of the model of Christian charity, describing each person's responsibility to the community as the human component of a divine covenant.

“We must be knit together in this work as one man, we must entertain each other in brotherly affection, we must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others' necessities," Winthrop said in his address.

In 2002, Forrest Church, senior minister of Manhattan's All Souls Unitarian Church, explored the common philosophical principles of America's founders in The American Creed: A Spiritual and Patriotic Primer.

Considering the Declaration of Independence as an outline of the inherent link between faith and freedom, Church wrote that the common good in America is "grounded in a set of virtues — liberty, justice and charity" that the nation's founders established as touchstones of a good society.

The founders were products of the Enlightenment, a time when thinkers began to give greater credence to humanity's power to reason and to build a better world. But their ideas about faith and citizenship were grounded in an understanding of an ancient heritage.

“Civic virtue really goes back to Roman times," says Andrew M. Manis, an assistant professor of American religious history at Macon State College in Macon, Ga. You "have to think in terms of justice" if you are applying the principle to America's founders, he says.

“Our Founding Fathers, of course, had a rather attenuated understanding of justice because they did not include persons of color or women as real human beings," Manis says. "In one sense, they were persons of their time."

'Black Civic Virtue'

The black clergy members who led the Civil Rights Movement might trace their activism to a similar basic understanding of the Christian faith and to a different, specifically black interpretation.

"There is no more significant tradition of civic virtue, in all the best sense of that term, than in the black freedom movement of the United States at least since the beginning of the 19th century," says Stewart Burns, author of To the Mountaintop, a 2004 biography of King. "All black ministers touch into that tradition in one way or another. You might call it black civic virtue."

These ministers preach from a religious mindset that is rooted in the black social gospel, which Burns views as grounded in the ancient Hebrew scriptures of the Old Testament. The leadership of a figure like DeLaine springs from an activist tradition modeled on Old Testament leaders such as Moses and the prophet Amos. It stresses faith in God's commandments as essential to free oneself from subjugation and slavery.

Faith and faith alone, it preaches, is what the believer must possess to achieve righteousness and justice in this life, on this earth. "For them, it's not growing out of classical philosophy as much as growing out of prophetic religion, prophetic Christianity," Manis says.

King preached about "an ever-flowing stream" of justice and righteousness. To him, the Civil Rights Movement was one in a series of revolutions, Burns says. The first was the American Revolution; the second, the Civil War.

The Civil Rights Movement, which was "faithful to the original ideals" of the nation's founders, was the third revolution, Burns says. This was all grounded by King's "deep commitment to the Declaration of Independence," which he viewed as a promissory note.

"Whatever Jefferson meant, King feels that's not really relevant," Burns says. "The words were sacred words, and they spelled out a promise, a covenant that America has yet to fulfill." In essence, King believed the Founding Fathers' original ideals forged a promise of equality to each person, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, or national origin. But the promise went largely unfulfilled during his lifetime.

Change and the Status Quo

Civic virtue had a distinctly different meaning to the white leaders in Summerton than it did to DeLaine. By the late 1940s, segregation had been a way of life for many generations. For whites, protecting that status quo was seen as the right way to be and to live. It was important to people in power.

During segregation, the statistics on education in Clarendon County supported the claims of the Briggs v. Elliott plaintiffs. The whites who ran the public schools appropriated money in such a way that their children came out ahead, even though blacks outnumbered whites three to one at the time.

The Briggs plaintiffs had no intention of starting a social revolution, but others took on their cause and turned it into just that.

Civic virtue, the concept that faith and values should shape one’s behavior in public and private life, is still at work in Clarendon County. Descendants of the Briggs plaintiffs are working for better education and better race relations. So is retired educator Joe Elliott, whose grandfather was the white school board chairman named in the lawsuit.

Clarendon County leaders fiercely defend their ability to bridge the racial gap, as do Summerton's white mayor, its black police chief, and some of its clergy. But while communication and interaction between races has improved, the town's past has largely failed to shape its present. Today, many people will not even discuss the Briggs case.

When reporters — even student journalists — approach residents with questions about the lawsuit and its legacy, many Summerton citizens ask why anyone would want to rub salt in such an old wound.

Material tracing the rich religious, cultural, social, and political history that led to the Briggs lawsuit is not readily available to the public, even though two generations have lived and been educated in South Carolina and the United States since the Brown decision.

Today, the implications of Brown and Briggs for education, civil rights, race relations, and civic action shaped by faith remain enormous. In this instance, some might ask, "Why not let bygones be bygones?"

Others worry that the words of philosopher-poet George Santayana are more appropriate: If South Carolina and the nation do not remember the past — especially the ill effects and inequities of segregation — we might all be doomed to repeat it.

Cecile Holmes died in September 2022 at age 67. This article, which is no longer online anywhere else, is published here with the permission of her brother, Jim. To read more about our 35-year friendship, click on the links below.