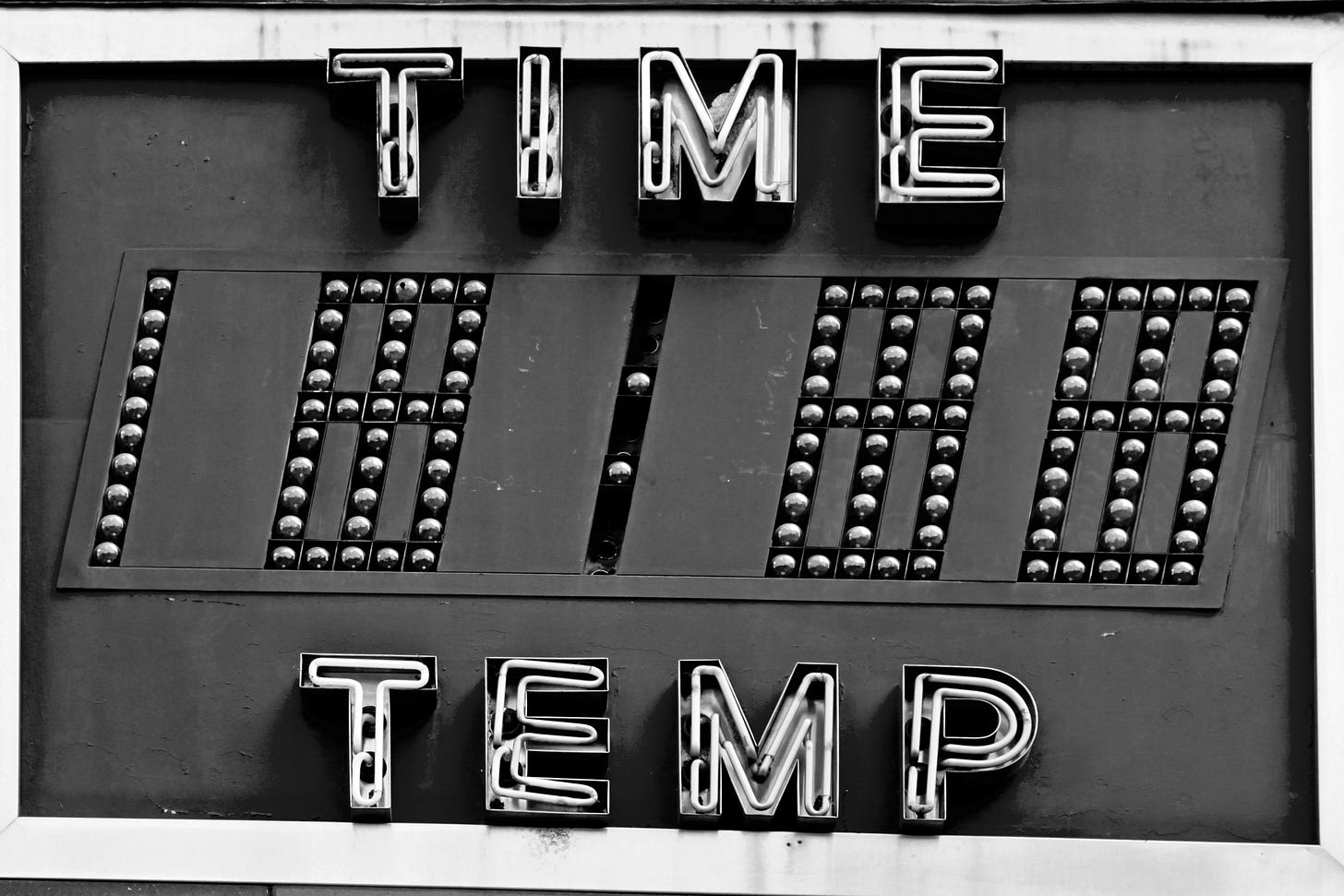

Stuck in Time

Learning how to deal with an unanticipated case of the non-musical blues

One thing my late father and I shared, along with music and movies, was a fascination with time. How it bends, accommodates, frustrates. The pressure and adrenaline rush that time, or lack of it, brings during life’s most unexpected or unanticipated moments.

My father’s fascination, however, was with the end of time. A teenager of the Cold War 1950s and the space race, then later married with children during the Vietnam era, he talked often about life in a post-apocalyptic world. He recalled the bomb shelter safety drills that students went through in school, recognizing even then how feckless they would be if a nuclear weapon truly was descending.

He became immersed (obsessed?) by the work of Tim Wistrom, who is best known for his post-apocalyptic paintings of Seattle and other major cities underwater. (Seattle was one of my parents’ favorite cities, in large part due to the space needle, the design of which also captivated him.)

When I was a child, Dad’s focus shifted from the grade B-movie science fiction films of his youth to the later Charlton Heston oeuvre that included “Planet of the Apes,” “The Omega Man,” and “Soylent Green,” the last of which was released the year of his spasmodic torticollis diagnosis when I was 8. When the “Twilight Zone” became a hit in syndication, he had me watch episode after episode with him, especially the classic where Burgess Meredith plays a bank teller who wants nothing more than to be alone with his books. That is, until a nuclear attack wipes out the rest of the world, leaving him alone.

Ironically, watching these end-of-the-world films did not bring my father down emotionally as he struggled physically — mightily and painfully — during the second half of his life. Also ironic: Other than a brief, frenetic period of creativity after he was first diagnosed, my father no longer actively pursued the painting and sculpture that dominated the first half.

Instead, he preferred to wander through his days as slowly as possible, taking in what he wanted to know and discarding the rest.

It was, you could say, his way of putting time on hold.

The Existential Crisis

I found myself thinking a lot about time and my own creative muse in 2023, much more than in years past. It’s been 50 years since my father first went to the hospital, and I am now 25 years older than he was then. It’s been 16 years since he died; I’m only eight years younger than he was now.

Playing with numbers — something I’ve always done —can conjure up memories and help you not to forget where you are in this life. But this past year, those numbers and others have made me pause more often than not. They have led me to wonder if what I do and have done — as a husband, parent (now grandparent), partner, friend, writer, photographer, learner — mean something to others. And more important, what can or should I do in the time I have left?

Welcome to the land of my existential crisis, the punchline of sorts to this story.

Only a handful of people — if that many — know about said crisis, and only the professionals I’ve talked to know the extent of it. I wish I could put my finger on a single moment/event that caused it to occur, but I can’t. More predictably, it’s been an accumulation of things over time, starting with the pandemic, which my business decided to wait out in life’s version of a porta-can.

Figuratively speaking, I was too busy holding my nose with a mask on to seek a clear path.

An Unsettling Place

In a lifetime of juggling, I’m used to a lot taking place in a 12-month period. But 2023 brought with it a series of joys and challenges that brought me crashing into an unsettling place headfirst.

Family: Celebrating the birth of our first grandchild (Marley, Kate and Matt’s daughter) with a second (a boy for Nick and Conner) on the way; seeing Emma’s first national tour and professional show; taking a memorable trip to Texas with Ben; and being part of large family gatherings in New Orleans, North Carolina and, most recently, in Wintergreen for Thanksgiving.

Personal: The realization that it’s been 30 years — more than half my life — since I left Texas; the stubborn aches and pains — specifically an SI joint that sends me to the chiropractor more often than I would like — of approaching 60; unforeseen challenges in a couple of key relationships; watching people I care about struggle and not knowing how to help them.

Professional: 40 years as a working writer, 10 years in my second career as a photographer, and a decade of operating my own small business.

The result: I hit a wall with more force and frequency than at any time I can remember.

On more than one occasion, I found myself writing variations on the same sentence over and over, only to hold down the delete key as soon as or even before I typed the period. Some days I just didn’t want to get out of bed.

As someone whose greatest professional fear is losing the muse — see my dad, above — I realize that I was depressed. Not “deep dark hole that leads to nowhere” depressed, but pretty close. And it has not been easy to climb out of it.

Business Ups and Downs

My business model is pretty simple. The majority of photography I do to pay the bills (mostly events) is seasonal, with the slack being picked up by freelance writing. During COVID, most of my photography business disappeared for two-plus years, meaning I found myself scrambling to write for as many clients as I could find. And that, in turn, led to burnout, which in turn led to this version of “Our Reality Show.” Moving to Substack was my attempt to fall in love with writing again.

Cut to three years later. If the pandemic’s arrival felt like our collective society went from fifth to first without hitting the clutch, 2023 has been a massive pendulum swing in the opposite direction.

At points during the year, I watched friends and colleagues ramp up their post-COVID lives as smoothly as some make the transition from a manual transmission to an automatic, acting as if the pandemic was a collective blip in their day-to-day existence. Meanwhile, depending on the visual analogy you prefer, I felt like a duck in the water — calm on the surface and paddling like hell underneath just to stay afloat— or Fred Flintstone.

Unfortunately, as my photography business slowly returns, the freelance writing continues to be hit and miss, which is not a surprise. Many of my journalism colleagues have struggled as traditional media continues to scale back greatly or, in extreme cases, disappear altogether. Earlier this month, the employment firm Challenger, Gray and Christmas said almost 2,700 jobs have been cut in 2023 across broadcast, digital, and print media. That is scary on many levels.

A couple of clients I have worked for have eliminated or cut back the number of issues they publish, which results in less work (and revenue) on my end. Others are paying less — in a few cases much less — than they once did.

On the good side, I picked up a couple of new photography clients this year, which made the months of May to July and September to November an extremely busy yet productive period. A couple of clients who pressed pause for the previous three years also returned, but not everyone is back yet.

While I celebrate those small victories, I also recognize the process of rebuilding my professional life twice in a decade has worn on me, probably more so in 2023 than at any point in my career. And with some exceptions, it also has impacted my creativity and motivation in a way that left me feeling unmoored more than usual.

The Search for Capacity

Everyone, to a certain extent, uses the word “time” as an excuse. Think of how often you’ve heard or said, “I don’t have time to…” before filling in the blank.

In some cases, when life is roaring at you 24-7, that statement is true. There is only so much we can cram into a single day, but more often than not, “time” has become a catch-all phrase, a synonym of sorts for “capacity.”

I’m not playing a game of language arbiter here, but instead sharing one salient thing I’ve learned since my emotional/spiritual universe was covered in a soggy, wet quilt several months ago.

When we are clear headed, we “make time” for the things that feed our souls. We are willing, even eager, to sacrifice sleep and make an early withdrawal from the next day’s energy source to do a particular activity or thing that we need to do. When things become muddled, finding that energy to do those things — anything, really — becomes harder and harder.

And harder.

The need to write and take photos — to capture moments in time — is embedded in my DNA. Throughout my life, I’ve leaned on writing as the way to process my emotions, and over the past 15 years or so, I’ve relied on photography to help me focus on the world small and large. The farther I got from those things, or from having the desire to do those things, was emotionally frightening. Far more than I ever realized.

Earlier this year, my wife Jill said she wanted to go back to church, something we had done only sporadically since our children were little. My relationship with organized religion has been fraught, even though I’ve surrounded myself with friends of different faiths who are all in their own ways deeply religious.

But, in some ways recognizing or perhaps foreshadowing my own unease with the state of things, I agreed to go with her. And it was the right call. We’ve found a place where the values match our own, absent the political BS that mires so many institutions of faith. It has been a salve during a rough period.

When I hit a large wall this fall, I spoke to someone, first through a telehealth service and then to a counselor in person. The first was as impersonal as I thought; the second was tremendously helpful, proving to be the reset I needed by helping me to re-focus with intentionality on what I love and need in this world. I’ve also been able to reach out to two longtime friends (you know who you are) who’ve also been very helpful, mostly through listening to various parts of my tale.

Finding Renewed Focus

One aspect of the refocus was recognizing that I’m in control of changing my circumstance. To become unstuck, I need to instigate the changes I know I have to make. I need to rely less on old habits and create new ones, much like Jill did when she decided to seek out a church family.

This is something I’ve long known intellectually but refused to accept emotionally, preferring instead to randomly wait for what’s next and then fly through the next personal/professional adventure. Living in that gray, acknowledging that I’m rarely in control of what happens, has been a huge part of my journey to this point, and it has led to some wonderful experiences.

But, as I start to look at the final third of my life, I recognize I also must work to be more intentional personally and professionally. I’ve found myself looking for ways to better control my camera, moving away from automatic and seeing what happens using manual settings. (A small step, it may seem, but one that’s big for me.) I also decided, after writing about mental health on a personal and professional level for years, to talk about my own here in this space.

My struggles, by comparison, may seem minute or insignificant given the gifts and privilege I have. Everyone struggles at times in their lives, and I’ve learned not to minimize others. I hope, by reading to this point, you won’t dismiss mine.

Last month, as I started to recalibrate and come out of this funk, I wrote the following: A decade plus into doing this, I recognize the freelancer’s life is a combination of feast and famine, with occasional forays into utter desperation (“What do you mean I have nothing on the calendar for the next four weeks?”) and gluttony (“I can make a third of one year’s take home in a single month … as long as I can survive”). Like anyone in this line of work, I’ve learned to understand, expect, and even appreciate the ebbs and flows.

The annual winter ebb is here, and it’s real. But more real, at least I see it, is fighting through the ebb and bringing my creative muse along for the ride.

All I needed to regain that capacity, it turns out, was intentionally working — and accepting — that it takes time to do so.

Glenn,

I’ve always said you have a great eye—not only in photography where you have to decide what gets in the frame or not. Now it can help you reframe how and what you see in life. Thank you for sharing with such vulnerability.