As the returns started coming in, I met my wife at our favorite dive bar a couple of blocks from our home. We live in Alexandria, Va., only a few miles from the White House, and I wondered what the scene would be like.

I should have known.

Hockey and college football were playing on the TV sets shortly after 7 p.m. Given that it was a Tuesday, you don’t expect a crowd, even though the place somehow is packed nightly for karaoke, where folks go to party, drink, and forget. The bar had a handful of people, none of them the happy hour regulars, and a couple of guys were eating at the table. They looked like out of towners, possibly contractors with government-related business, who stay at one of the hotels near our neighborhood Metro station.

A guy I know comes in once or twice a week and takes over the pre-karaoke jukebox. We share much of the same taste in music and have extended discussions about bands, a common talking point not related to sports or politics. His music choices on this evening are particularly inspired — a nice mix of politically related punk combined with tunes such as Elvis Costello’s cover of “(What’s So Funny About) Peace, Love, and Understanding?”

I join in with my own six pack — The Chicks’ “Gaslighter,” a couple of X songs (“I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts” and “See How We Are”), Jason Isbell’s “Hope the High Road,” Dave Alvin’s “Fourth of July,” and (for obvious reasons) Sufjan Stevens’ “Chicago.” The last one is a balm — a throwback to happier times — on an uneasy night. The guy interrupts my list with another inspired choice — Alvin’s live version of “So Long Baby Goodbye,” a track that I have long said I want as the entrance music at my funeral.

Jill is nervous, worried, and scared. I shut off her phone and turn mine upside down, occasionally and unfairly looking to see the ticker that is starting to report the results.

No one is talking about politics. Mercifully, “Peaceful Easy Feeling” — a song I hate with all my might, regardless of circumstances — is not played on the jukebox on this night.

Small Community Life

Eight years ago, long before we moved to Alexandria, I had the same uneasy feeling that I did on Tuesday. When Florida was called in 2016, I went to bed, already knowing the outcome. Florida was not part of the equation this time. The same goes for Texas, which despite optimism that it had turned purple has not supported a Democratic president, senator, or governor since 1994.

That was the year after I moved from the state, having left to take a newspaper job in a small North Carolina tobacco town. It was a career opportunity that I thought had me on a path to eventually run my own community newspaper.

At that time, not thinking my work was ever the same quality as those found in metropolitan newspapers or magazines, management was the way to achieve some semblance of financial stability. Community newspapers, in those days, were a mix of crime blotter, coverage of local government, newborn announcements (a.k.a. Infant police lineup pictures, 2 inches by 3 inches, spread across six columns), obituaries, community fairs, high school sports, and the occasional heartwarming feature. Stories that mixed two or more of these elements were rare but welcome.

Moving to Reidsville, a community just north of Greensboro, changed my life forever. It’s difficult not to overstate how much but suffice it to say it was in ways I never thought possible.

The first 36 years of my life were spent largely in and around two industrial working-class towns. Texas City, the Gulf Coast town where I grew up, was and is rooted in the petrochemical and energy industries that dominated (and continue to largely dominate) the Greater Houston area. When I moved to Reidsville, I didn’t know that the tobacco and textile industries that fueled the economy would be decimated in the wake of cigarette industry lawsuits and North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

At the time, I was a hustle junkie, quick to work a 70-hour week in pursuit of some sense of professional glory, naively thinking that would bring me personal fulfillment. We stacked up the awards, but I also divorced and remarried during a tumultuous three-year period.

Many of those awards were for a series of stories we wrote about the sale and downsizing of the American Tobacco Company, Reidsville’s longtime economic engine. Meanwhile, textile plants were closing left and right as operations were being moved overseas. Jobs that had been part of families for generations were being lost.

Democrats were talking about a global economy, and the need for more retraining and education to compete. Families forced to reconfigure their once stable, though by no means exorbitant, lifestyles were left feeling abandoned by their employers and the party that had long defined itself as the one that was for working class people.

The exodus, not just in Reidsville but in similar industrial-based communities across the nation, was just beginning.

The Quest for Power

In 1943, psychologist Abraham Maslow created a “hierarchy of needs,” a five-level pyramid that helps understand how humans are motivated to behave. Maslow believed that some needs take priority over others. The first two — physiological (food, water, shelter, sleep) and safety (security and stability) — are essential for survival and must be obtained before the others (love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualization) can be met.

Exit polls from Tuesday’s election show how the priorities of voters greatly differed. For Republicans, the most important issues were the economy, immigration, and foreign policy. For Democrats, it was the state of democracy and abortion.

As a Democrat, I share those concerns, and I’m worried about what the next four years will bring. I can’t imagine what it must feel like to be a woman today, or a person whose rights are being directly threatened on both a policy and a literal level. I won’t go into my feelings about Donald Trump or the feelings I have when people look past the prosecutions, the misogyny, the authoritarian impulses.

We are fooling ourselves if we think this election was about character or morality. It was about power. Who has it, who doesn’t, and what people who are generationally angry and frustrated are willing to do to quash threats real and perceived.

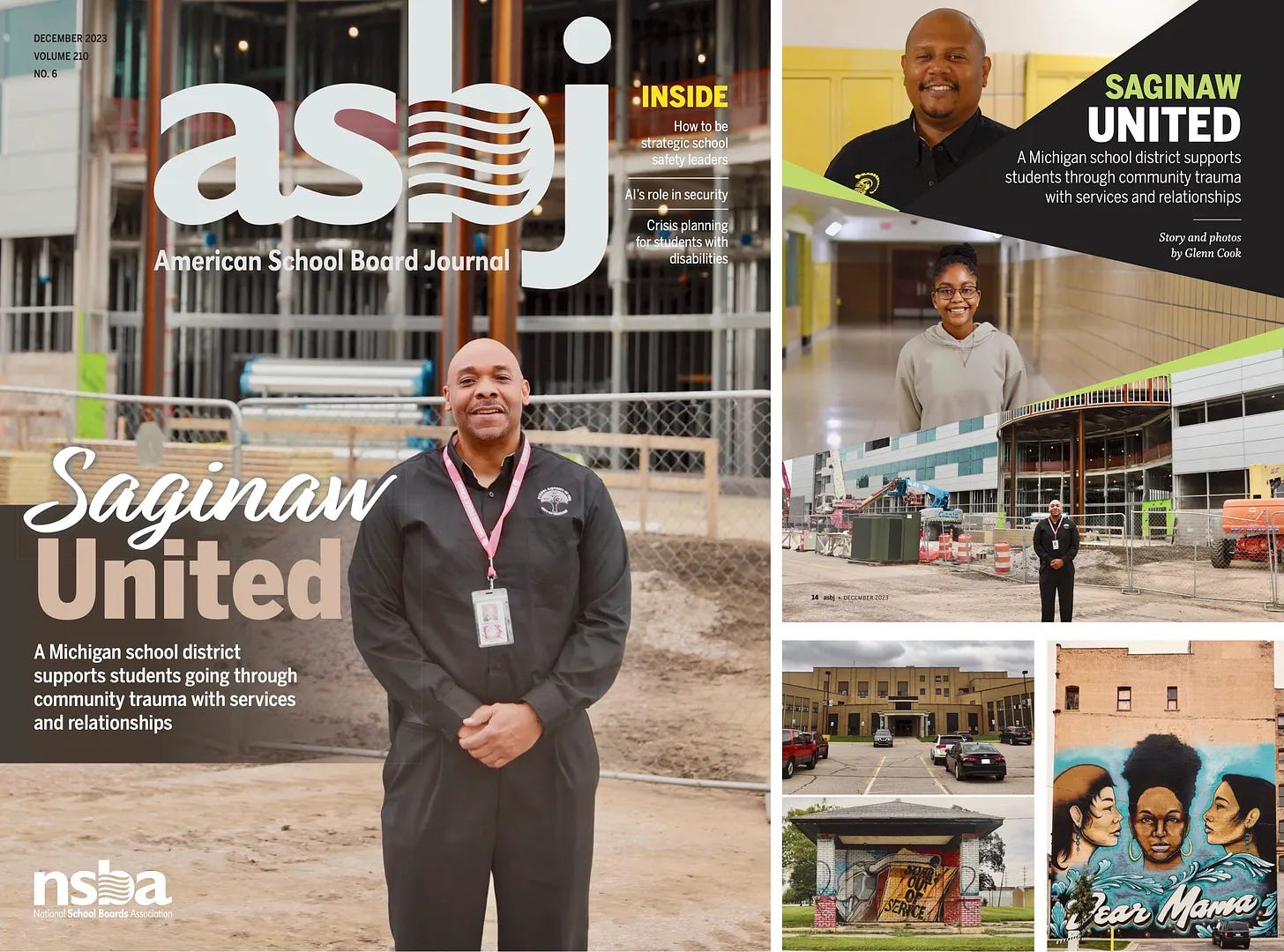

Last fall, I went to Saginaw, Mich., to write a magazine story about the schools in a once-thriving city now plagued by violent crime. In the mid 1980s, Saginaw and its surrounding communities had more than 60,000 people working in a dozen General Motors plants. Today, only one plant remains in the city, and most of the jobs are out of state or overseas,15 years after GM filed for bankruptcy and the city’s unemployment rate grew to 23.5 percent.

The once-proud union town has lost more than half of its population, an exodus that started as the plants closed and no jobs were available to replace them. “Once the income base is gone, the population follows,” board member Charles Coleman told me.

Coleman, a former city councilman, and others whose families had generational ties to GM said they are only now recovering from the losses that started following the signing of NAFTA. The community’s economic base now is medical rather than industrial, and its politics have shifted.

“Betrayed? Sure, people feel betrayed,” Coleman said. “How could they not?”

On Tuesday, 65 percent of Saginaw County’s 160,490 registered voters went to the polls, with Kamala Harris losing by 3,200 votes, according to unofficial results. Michigan, a swing state with a Democratic governor, and its 15 electoral votes went to Trump by 84,000 votes.

Other Concerns

In 2001, Jill and I moved to Northern Virginia with our children. We wanted to give them more opportunities than they would have growing up in a small town and in a position at the time to shift careers and make the journey. For 12 years, I worked in publishing for a non-profit education association but was laid off in May 2013.

Thirty years after I started my career, I was unemployed for the second time. The first, in 1987, lasted nine days. The second was the last. I was fortunate; my wife had a good job with benefits that allowed me to start a freelance career.

I went back into hustle junkie mode, starting careers as a writer and a photographer and building a business that grew every year until the pandemic. After a devastating couple of years financially (and emotionally) due to COVID, I’ve struggled to rebuild the business to where it was pre-2020.

As I approach 60, I’ve come to recognize that I don’t have the same level of hustle I once did. As much as I enjoy and want to work, other things (specifically being a supportive spouse and a trusted advisor/mentor to my biological and extended family) are more important. And I’ve seen the tea leaves when working in mediums that have only become more unstable.

This year alone, I’ve had six friends or acquaintances — all in some form of the media business — lose their jobs due to corporate cutbacks. All, like me, are closer to the end of their careers than the beginning. All, like me, are white.

In conversations, we talk about the “what’s next” part. I ask how they are doing, not financially but emotionally, during an unsettled time. We are all fortunate to be in positions where we don’t have to worry where our next meal or mortgage payment will come from. The dings to our wallet are real, but not necessarily dire. The dings to our professional identities? That’s another story for another day.

An illustration of the disconnect can be found in the desire people have to talk about what has happened. The election — what led up to it and speculation about what will happen in the near and extended future — will be forensically dissected for days, weeks, months to come by those who were part of the losing team. The winners don’t want to talk about it; they just want to move on to the tasks on their agenda.

Today, after an early morning doctor’s appointment, I went to a small locally owned deli near my house and got a bagel. The owner has managed to hang on despite the loss of customers who are still working from home and not coming into the office. I asked her how business was doing and she gave me a shrug.

“It’s tough,” she said, her voice resigned. “Costs have gone up. Things are up and down. I don’t think we’ll ever be back to where we were.”

We didn’t discuss the election results. She has other concerns.

We are wrecked here. The daughter is particularly distraught, hysterical even.

I don’t know what has happened to the country I thought I knew. Everything feels ugly and heavy.

I know it's cliché but the idea that the left is mainly "coastal elites" resonates deep here in the Midwest. The truth is the GOP is masterful at messaging and staying on message. They've bought all the way into the idea that "facts tell and stories sell."

Meanwhile the left (my team, btw) is constantly trying to workshop talking points and playing tone police. Tbh, picking Walz was a masterstroke--there is a Tim Walz living on every block up here. Having him tone down his messaging and playing nicer on stump speeches was like stepping on a rake.

"We won't go back" is a great message...unless your town was gutted by NAFTA and you've spent your whole life waiting for the American Dream to come true for you.