The Day I Kidnapped My Grandmother

Taking her to a movie was selfish, but in many respects just what she needed

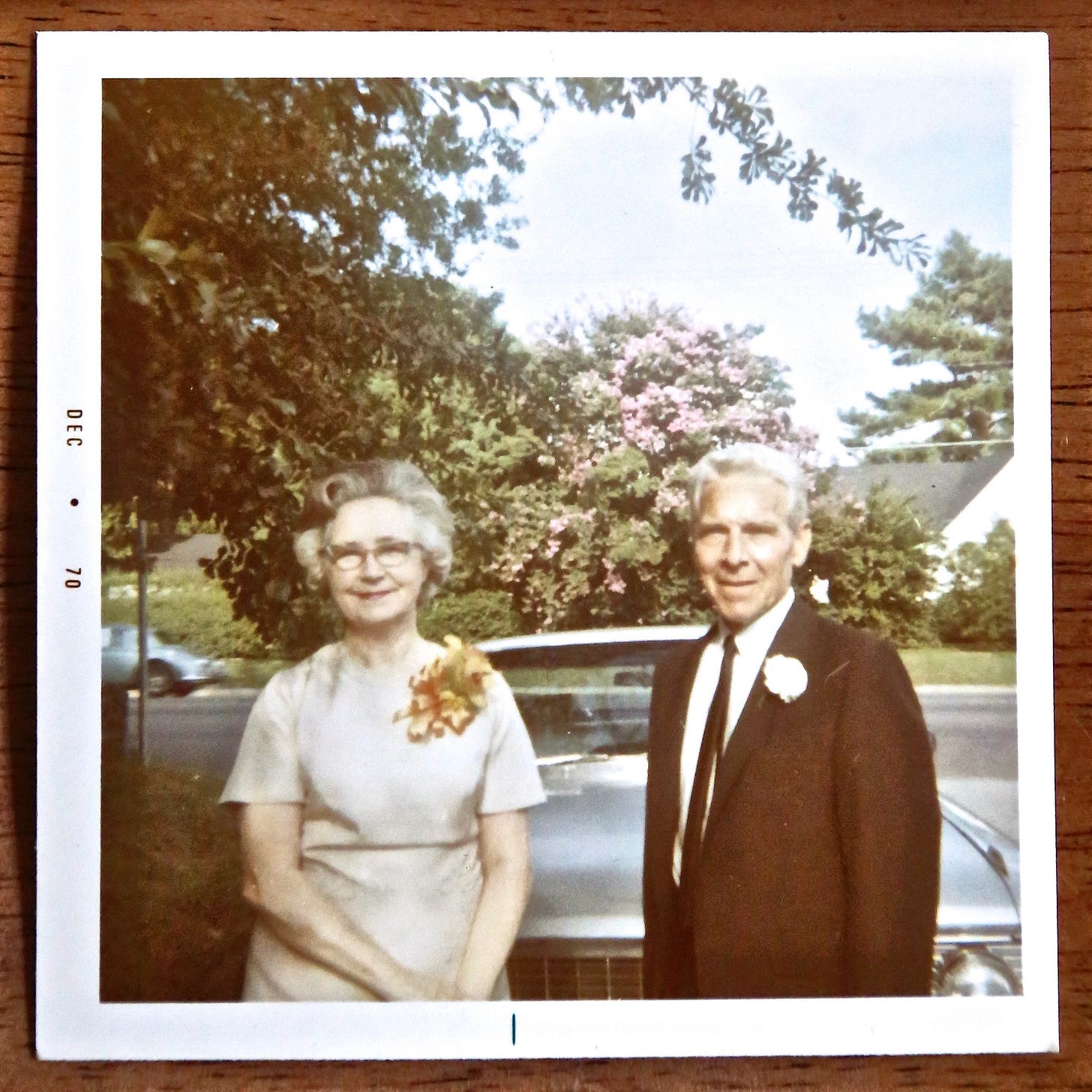

My grandparents, Vera and John Cook Sr., in December 1970. At the time, they had been married 40 years.

My grandmother sat in the dark auditorium and dozed to the ragtime music.

I ate my popcorn and glanced at her. Occasionally she would wake and look at the screen.

The movie was long, so she had a good long doze. She didn’t drink the Coke I had bought her with money she had given me earlier in the day, so the ice melted and left it flat.

I wished I knew what she was thinking.

Maybe it was relief. Maybe it was sorrow. Maybe grief. I really wasn’t sure. After all, he had been her husband for more than 50 years, the last five in and out of hospitals. They argued and fought. They made up, keeping their distance while never being apart.

He was cantankerous, a do-it-my-way man’s man who really wasn’t.

She was an independent sort, a flapper in Louisiana who told stories — true ones at that — of getting rides to work with Huey Long and hearing Jimmie Davis perform his new composition, “You Are My Sunshine,” the day it was written. She was married eight years before her first child was born. Her second, my father, came two years later.

She listened to music and cooked in the kitchen. She would slice raw tomatoes she bought from the woman with the big garden down the street.

Notes from my grandmother’s high school history class and a photo of her in 1921 at age 16.

The lights came up. Now she would have to go back and visit the mourners.

“Thanks,” she said as we left the theater, squeezing my hand and nearly cutting me with her serrated wedding band.

I drove. It was an adventure because I was only 16 and they had a big Buick that was almost impossible to park. I knew her thank you was genuine.

I also knew no one would understand what I had done. Kidnapping my grandmother, to anyone on the outside, was not a great idea. Taking her to a movie I wanted to see was a selfish act.

We continued to hold hands as we went out to the parking lot on that drizzly December day. I steeled myself for the drive home and hoped I could back out of the parking lot in the big silver Buick without hitting someone. It was a 50-50 shot at best.

Grandmama had never driven. She was 76 now and not about to start, so asking her was out of the question. But as she looked at me with her eyes so tired, a washed out look that took me back to the first time my grandfather was in the hospital, she smiled and squeezed my hand again.

The wipers streaked the windshield; they hadn’t been changed. All I could do was be critical because I didn’t know how to change them. Still wouldn’t, if forced.

She didn’t care. I was her only grandson, and she knew how to spoil me. It was the same technique she had used with my father and it worked. She came from an era that “respected” men for being “men,” even if it meant muttering the word “bastard” under her breath.

We drove in absolute silence for a mile, which was odd because we were both talkers. Some say I got it from her; my mom has got it, too, even though the two weren’t blood. Grandmama was one of the ones I could talk to about anything and not be scared.

The wipers muddied the windshield. They weren’t much help at all. We drove across town, probably too fast if my mom had been in the car. But my grandmother didn’t care.

“It was a good movie,” she said.

We got home and the family was there. No one said a word. They didn’t know what to say. My aunt (my dad’s sister) and uncle scowled at me and shook their heads. I knew I would get a talking to later.

Soon I could smell the food. My grandmother was doing what she did best, cooking for the family. It was December, so there were no tomatoes this time. She served a thin flank steak, deep fried and battered. Coffee from that morning remained on the stove.

She didn’t talk much that week or next. It was the Christmas season 1981, and she didn’t think it was appropriate to ruin the holiday season for others. She didn’t cry, at least not in front of me. The only time I saw her do that was when she missed me leading a youth prayer at church because she got there too late.

I got my talking to from the people who didn’t understand my motive behind the kidnapping. They didn’t really care what I thought.

Over the passing months, as she dwindled in size and moved slowly toward the plot next to her husband, my grandmother never brought up that day. Several years later, in the middle of the night, I sat on the floor next to her as she lay on the couch. My father was calling for an ambulance.

I held her hand again. The wedding ring cut into it some more.

“Do you remember ‘Ragtime’?” I asked.

She nodded. I could barely see her in the dim light.

“Yes, it was a good movie.”

The Story Behind The Story

Most of this essay, parts of which have been newly edited and updated, was written in March 2001, soon after I moved to Northern Virginia to start a new job. I was living temporarily in Fredericksburg, Va., in an apartment leased by my wife Jill’s cousin, James McGhee. At the time, I was commuting by train to Alexandria while Jill lived in North Carolina with her mother and our kids until the school year ended.

March has long been a month of major life events in our family, second only to December and just ahead of August. Sunday was my wife Jill’s birthday. Today is my parents’ 59th wedding anniversary.

Nineteen years ago, on my parents’ 40th anniversary, the person I called my second father died. Bill Waranius, half of a childless couple I lived across the street from, passed away two days before the birthday of his wife, Fran. March 29, ironically, is James’ birthday.

One rainy, drizzly morning on the train from Fredericksburg to Alexandria, I saw a woman who looked remarkably like my grandmother. It felt like I had seen a ghost, and I always regretted not speaking to her. The rain reminded me of that day at the movie and I started writing down those still vivid memories.

As I write this, 22 years after that initial essay and 41 years after the “kidnapping,” I’m on a train again. This time, I’m going from Alexandria to New York City, the place where our family’s life changed forever when our son, Ben, made his Broadway debut in the revival of, yes, “Ragtime.” Tonight, I’m getting together with my son and members of my extended family — Bernadette, Ginno, and Elie — to see one of my favorite bands in concert.

Today at Union Station in Washington, D.C., I saw an elderly woman standing in line, waiting to get on a different train. She bore a passing resemblance to my grandmother near the end of her life. I asked where she was going.

“South,” she said. “I’m going home.”

Omg Glenn, I got to the line where your son made his Broadway debut in Ragtime. Wow.

This was just lovely.