The Details Matter

An essay on writing, musicians and what others have taught me

Fresh out of high school, I started my journalism career in the summer of 1983 at my small hometown paper on the Texas Gulf Coast. The newsroom included a city editor’s station with four large metal desks scrunched together. A fifth was located by the door to the pressroom and a sixth rarely was occupied.

The managing editor, Leo Lambert, had his own office, where he wrote scathing editorials labeling the political science professors at our local community college as “socialists.” The sports editor and writer were crammed into a tiny 8 x 8 room that had the feel of a converted closet.

Sitting at the single desk next to the pressroom, separated from the men’s bathroom by a thin paneled wall, felt like the equivalent of a childhood timeout, or the place where you went when the big kids didn’t want to play. It was the perfect spot for a naïve, socially uncomfortable 18-year-old working a minimum wage summer internship — read “bootcamp” — who had no knowledge of what was ahead beyond college that fall.

My peers — all but two were at least two to three decades older and each held varying tolerance levels for a curious teenager — would occasionally impart words of wisdom that I managed to file away. Cathy Gillentine was the hometown lifer whose lighted cigarette was perpetually pressed between her lips as she typed. Much to the city editor’s chagrin, she claimed writing a story should not take more than 15-20 minutes, tops. Another, Chuck Stevick, was a salt-and-pepper bearded former Marine who occasionally wrote freelance magazine porn, ostensibly for two reasons: to make ends meet and to keep the cheap beer flowing.

One late night, I handed a feature I had just written to Chuck and asked what he thought.

“It’s fine,” he said, “but it’s not visual. The best stories are the visual ones because you bring the reader with you. Otherwise, it’s just bad pop music.”

If It Don’t Bleed…

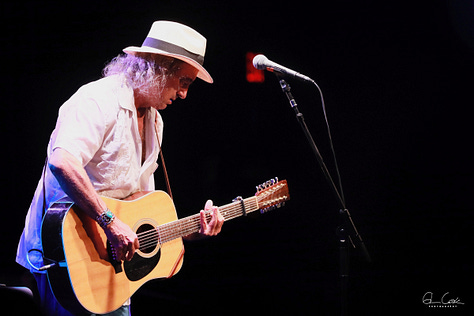

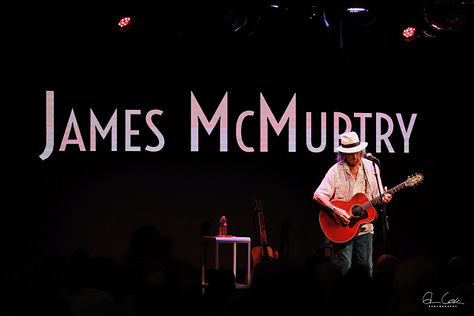

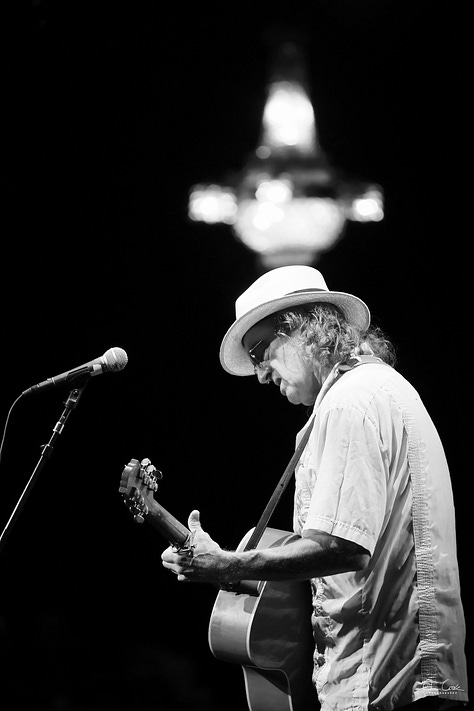

James McMurtry is the antithesis of “bad pop music.” The Austin-based singer-songwriter is a keen and barbed observer whose songs include the tiny details that we see daily but often pass by unless they’re called out to us. This talent, refined over 10 albums since 1989, comes to him by blood; his father was Pulitzer Prize and Academy Award winner Larry McMurtry, whose credits included the novels Lonesome Dove, Terms of Endearment, and The Last Picture Show as well as the screenplay to “Brokeback Mountain.”

Looking to improve my own storytelling, I became a major fan of the elder McMurtry, who wrote about his native Houston and Texas in minute yet colorful detail. (A “Terms of Endearment” movie scene where Shirley McLaine and Jack Nicholson ride down the beach was filmed in my hometown.) When the younger McMurtry released his debut album, the John Mellencamp-produced “Too Long in the Wasteland,” I gave it a shot.

That’s when the phrase from the former Marine — Chuck Stevick — crystallized for me as a writer, and I have since purchased each of McMurtry’s albums. I’ve also seen him live a handful of times, most recently when he came to The Birchmere in Alexandria, Va., for a solo show this week.

I admire anyone standing on stage with nothing but with a single instrument, and few do it with the skill of McMurtry, who gets a full sound out of the acoustic guitars — he played three Thursday — that serve his narrative driven songs. Like his father, most of his writing focuses on small towns and people who live on the periphery of the economic edge. Even his between song banter has a certain edge to it.

“It does maintain a certain amount of cynicism that McMurtry songs require, but nobody dies in it, so it’s a happy song,” he said before playing “If It Don’t Bleed,” the lead single off of his acclaimed 2021 album, “The Horses and the Hounds.”

He then told the story about the song’s origins. A cousin who had faced down cocaine addiction had no tolerance for complaining about life’s inanities. “One day I was bitching to him about something, and he said, ‘If it don’t bleed. It don’t matter.’ I wrote that down.”

The longest introduction was for the standout “Levelland,” a song McMurtry wrote almost 30 years ago as a tribute to Texas novelist Max Crawford, a family friend. Crawford, who died in 2010, was a contemporary of McMurtry’s father.

“Max was from Flodata, Texas, but Flodata didn’t fit the meter, so I changed it to Levelland,” McMurtry said of the song, which talks of a small-town parade where the marching band is “doing the best it can” to play “Smoke on the Water” and “Joy to the World.” The latter was written by Hoyt Axton and made famous by Three Dog Night.

“If you think you’re an artist and you think you’re profound,” McMurtry said of Axton, “think of the line ‘Jeremiah was a bullfrog.’ … He managed to change the world and gave it just a little bit of joy.”

The audience laughed. I’m not 100% sure McMurtry was joking, although you never know.

Reality is Not Optional

“Sometimes it’s a detail. Sometimes it’s a rhyme,” McMurtry said of his process. “Rarely it has much to do with reality … Reality is kind of optional in this trade.”

Reality is not optional in my trade, which can complicate the search for details. Last week, for example, I traveled to Saginaw, Mich., to work on a freelance magazine story on an urban school district that is persevering and thriving despite extreme community violence amid a catastrophic decline in population. This story required an in-person presence to be told properly; phone interviews could not capture what I saw.

Being on site also gave me the opportunity to look for the little details — in photos and words — that illustrate what folks like McMurtry and the former Marine taught me to seek out. From time to time, those details lead to sideroads, many of which involve music.

In Saginaw, I had a conversation with an administrative assistant who saw Elvis Presley in concert three months before he died; she had a picture she had taken of him at the show on her phone. I also had a 30-minute discussion about Sam Cooke, gospel music, and jazz with the school board chairman, a man in his early 70s. (I correctly identified that his favorite instrument is the tenor sax, then we started the interview.)

These conversations rarely make their way into the stories I write, but they greatly enrich my interviews and help build trust between two people who, until that moment, likely had never met in person.

And you never know where those tiny details will take you.

A Selfish Love for Live Music

The Birchmere crowd was into the show from the beginning, in part because a number were Texas natives who relocated to the D.C. area and work to get a slice of their home state’s music every chance they can.

In my marriage, the one thing I’m most selfish about is my love for live music. For the most part, my wife and I agree: The musicians I admire and love generally do not align with her tastes (Jason Isbell and Billy Joel excluded). That means I see most concerts solo, or with other friends I convince to join.

Two of our biggest disagreements, however, have together have been over shows I attended when — for happy marriage purposes — I likely shouldn’t have. While I regret the hurt I caused in both instances, I don’t regret the decision either time.

The first instance, nine years ago this week, was a show by The Replacements at Forest Hills Stadium in New York. The second, also in September but two years later, was Charlie Robison’s annual birthday concert at Gruene Hall in Texas.

In that instance, Jill and I had been in Austin for a long weekend. I was driving a rental to visit my mom in Houston while Jill flew home. Major storms erupted, leaving her stranded waiting for a flight, and she assumed I would drive back.

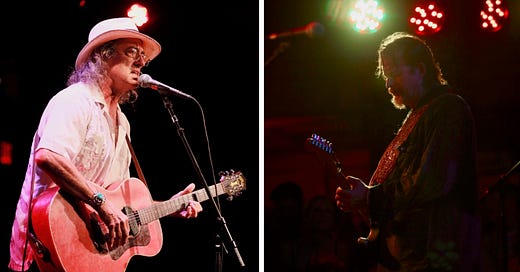

By this point, I was halfway to Gruene Hall, a legendary venue I’d always wanted to visit, to see Robison, who by this point rarely ventured outside the state, play at his annual birthday show. Selfishly, carrying my camera, I decided to venture on.

By this point, Robison and Emily Strayer of The Chicks — Natalie Maines wrote “Cowboy Take Me Away” about them — were long divorced. Robison was still drawing good crowds in the honky tonks he played, but like too many talented musicians who once reached the fringes of stardom, his commercial career was stagnant. He had produced only two studio albums and one live record since 2005.

For more than two hours, Robison did everything he could to burn down the venerable 19th century dance hall, mixing country and rock in equal measure with down home spit and swagger. The lyrics weren’t as sharp as McMurtry’s — few songwriters, with the possible exception of Isbell, are — but the storytelling was there.

Afterward, I tried to convince my wife that I was doing reconnaissance work for the next time Robison ventured out to the Northeast. Sadly, he never made it, retiring in 2018 after vocal cord surgery. He was in the slow process of making a comeback, having played a few shows earlier this year, when he was hospitalized in San Antonio and died last week from a heart attack and other complications.

Robison had just turned 59, an age I hope to reach in January. The concert I saw seems both like yesterday and a lifetime ago. As I listened to Robison’s music this week in tribute, I wondered — as we all do when something like this happens — what could have been if there were more time.

Leaving McMurtry’s show at The Birchmere, I spotted a person wearing a Robison T-shirt and nodded. He nodded back. Nothing else needed to be said.

Part of this essay was originally a review for Americana Highways.

Thank you for writing. You usually present both sides. Keep up the good work.