The Police Chief

For Ruben Espinoza, safety of Santa Fe's students and staff is an ongoing mission

Ruben Espinoza, chief of the Santa Fe Independent School District police department, stands in the central dispatch room at the system’s administrative office.

On the morning of May 18, 2018, Ruben Espinoza was just 13 days from retirement with the Texas Department of Public Safety when he received a call about a shooting at Santa Fe High School. Like other law enforcement, he rushed to the campus in disbelief.

“There’s no way there’s a school shooting in Santa Fe. No way,” said Espinoza, who became chief of the district’s police department in 2021. “When I arrived at the school, it was a parking lot. Chaos. Just chaos. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Law enforcement response has come under intense scrutiny in the wake of the February 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Fla., and especially following the May 2022 massacre in Uvalde, where 77 minutes passed before the gunman was killed. But in Santa Fe, where 10 people were killed and 13 injured, the district’s security and preparation and the response of law enforcement generally has been praised.

“This police department was in a very good place in 2018,” Espinoza said, noting the department had two well-trained officers already on campus and strong relationships with local and state law enforcement agencies. “If they’re comparing how we would react or what we would do compared to the Uvalde incident, the difference would be night and day.”

A New Door Opens

A Pasadena native who has lived in Santa Fe for a number of years, Espinoza had already been hired by the district’s police department on May 18, 2018. He was planning to take six months off before becoming a campus officer at Barnett Elementary School, which opened in the fall of 2019. Today, almost five years later, that vacation remains on hold as Espinoza runs the district’s police department, which has 19 officers and civilians who serve Santa Fe’s five schools.

Espinoza has a quiet, matter-of-fact demeanor and calming presence that he honed over three decades while working with DPS, much of that as a narcotics investigator in and around Houston. On May 18, he decided to head to the district’s central dispatching station to help handle calls about the shooting and the investigation to come.

“I headed straight over here and sure enough, it was chaotic, too,” Espinoza said as we sat in a conference room only a handful of steps from the dispatching station. “But I was able to help, especially when it came to working with the outside agencies like the FBI, because I knew them from working at DPS.”

About this series:

This is the third of six pieces that expand on my freelance article focusing on how the Santa Fe, Texas, school district is moving forward following an on-campus shooting in May 2018. To read the story, which appears in the December 2022 issue of American School Board Journal, click on this link.

Espinoza noted that officers at the high school were well prepared prior to the shooting. As an example, he noted, they had tourniquets on their police belts that were issued in the wake of the Parkland shooting three months earlier. The tourniquets were instrumental in saving the life of school resource officer John Barnes, who would have bled to death within minutes after his bracial artery was shredded by when three shotgun pellets ripped through his right arm.

“DPS officers did not have tourniquets on their belts in 2018,” Espinoza said. “If that’s not pre-emptive, if that’s not forethought, I don’t know what is. John Barnes would not be here today if they hadn’t taken that step.”

Espinoza went to work for the school district as soon as his retirement became official and never looked back. In the summer of 2018, he was put in charge of hiring the additional civilian officers who were brought in to fortify the district’s police department. Two years later, when Walter Braun became the city’s police chief, Espinoza was promoted to lead the district’s department.

“It was never in my sights to be a chief of police. Never,” Espinoza said. “I don’t know if you’re a believer in a higher being, but sometimes you’re put in a place where the doors close where you want to go, and sometimes the doors open when you don’t know you need to be there. That’s how I feel about this job.”

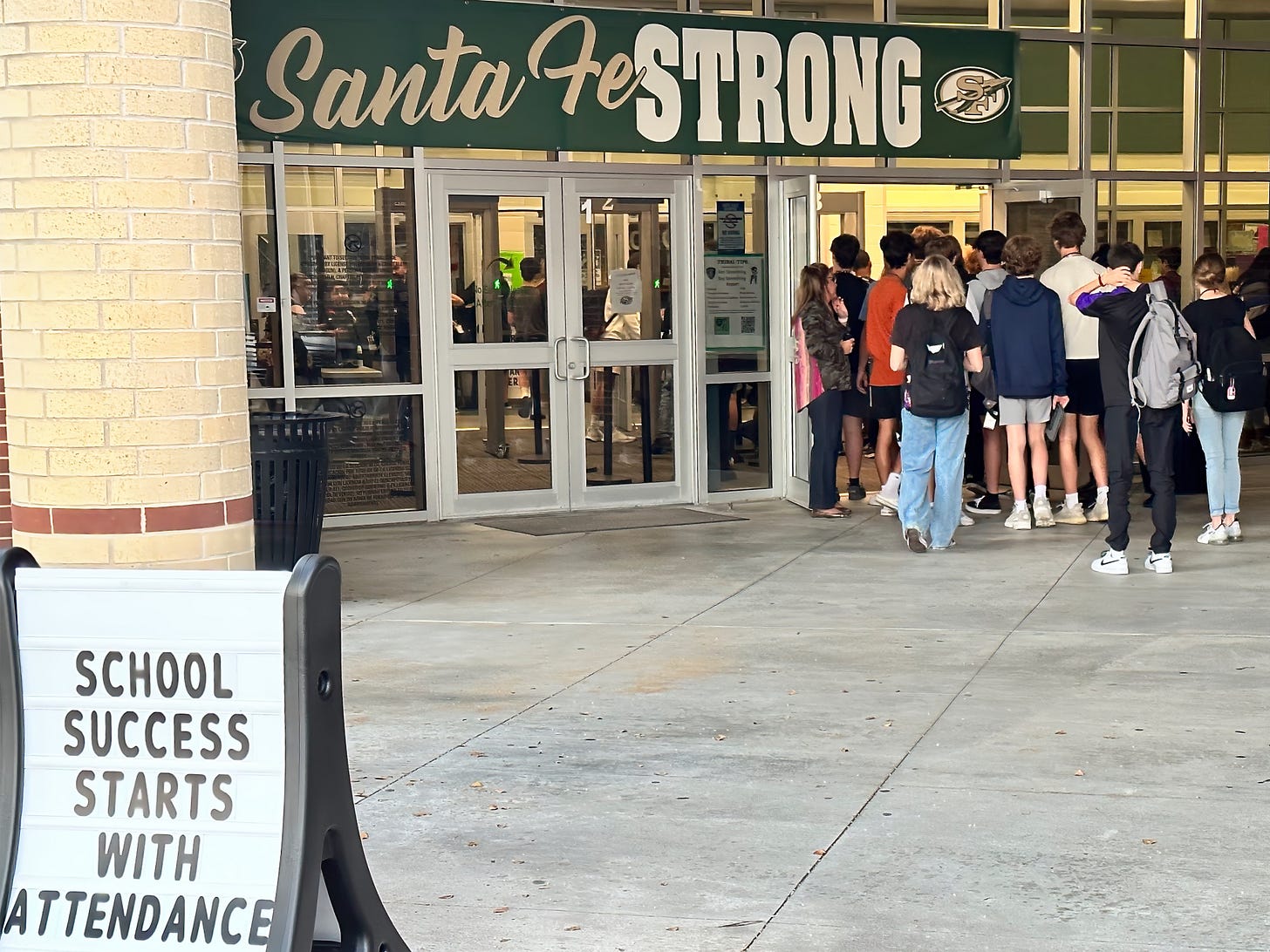

Students wait to go through metal detectors at the entrance to Santa Fe High School.

A ‘Hardened’ Presence"

In the immediate aftermath of May 18, repairing the high school and “hardening” Santa Fe’s campuses became the district’s top priority. The cost: $2 million that came from district reserves.

Bob Atkins, Santa Fe’s executive director of maintenance and operations, said in the summer of 2018 that audible alarms were put on every exterior door at the high school. Bullet resistant walls were added at the entrances to every school building and the central office lobby also was made more secure.

Now, everyone — visitors, students, and staff — goes through the metal detector at every campus. Backpacks and bags are inspected by a plain clothes security officer as a uniformed policeman keeps watch nearby. Visitors are directed to the information desk, where driver’s licenses are scanned and name badges printed, with the directive that the badges must be returned. Cameras monitor your every move.

Espinoza said students always “watch the cameras” and know that “If they’re hanging out in the stairwells that we’re coming to check on them.”

“Our officers are stationed at the schools. They are housed there, so they see the kids and talk to them every day,” he said. “If we are approached or if something comes up, we do our best to communicate to the person that we’re doing the best we can. We let our feet do the talking and our actions do the talking.”

As the fifth anniversary of the shooting approaches, however, some question whether the district’s approach to security is too extreme.

“To some people it may seem that way, and it’s difficult to get across to the community what we actually do,” Espinoza said. “Yes, we have metal detectors, door access, and video cameras in place, but people don’t realize there’s a human element in addition to the mechanical and technology elements we have in place as well. And that human element is what is most important.”

‘Police the environment’

School security and the on-campus presence of uniformed officers have evolved greatly since the 1999 Columbine High School shooting. According to a July 2019 study by the National Center for Education Statistics, more than half of the nation’s schools have sworn law enforcement officers on campus at least once a week. The number rises to more than 70 percent of high schools and 45 percent of middle schools.

In most instances, the uniformed patrolman’s title is “school resource officer” (SRO), but a growing number of districts, especially in Texas, have started their own internal police departments. Today, more than 300 of the state’s 1,026 public school districts use this model, according to the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement. Almost one-third of those departments — 97 — have been created since the Parkland High School and Santa Fe shootings in 2018.

Espinoza said there is “a huge difference” between SROs and officers hired and managed by the school district. SROs are employed by and report to a city or county law enforcement agency; district departments are run by a police chief who reports to the superintendent.

“SROs are hired to police the school, and their work is limited to the campuses where they are assigned,” Espinoza said. “They have to be very careful about stepping into administrative duties because that’s not what they’re hired to do. But in the district’s police department, our staff are also employees of the district. We’re making sure the building is safe, that the doors are locked, that the security measures we have taken are working.

“We are working side by side with the principals and the assistant principals when a child gets into trouble, and we have a role in figuring out what’s best for the child, whether it is to file charges or to face school discipline.”

Law enforcement officers already “live in a fishbowl,” Espinoza said, and that is only amplified in school districts where a mass tragedy has occurred. He stresses to new hires that “school-based law enforcement is the epitome of community policing” and that the field is continuing to evolve.

“We are not here to police the kids; we are here to police the environment and make the environment safe and secure,” Espinoza said. “We want our kids and our staff to know that when they’re on our campuses that they’re safe and secure.”

Research on the effectiveness of SROs and school district police departments is limited, but data has shown that increased security can make schools less conducive to learning, especially for minority youth. In Santa Fe, the district has held active shooter training for years for its officers; it became a state mandate in 2019. State law also requires officers to complete a course that focuses on mental health intervention, de-escalation, and working with children with special needs.

Espinoza declined to comment when asked if teachers or staff should be armed, a proposal that some Texas politicians have made since Santa Fe and again after Uvalde. Instead, he focused on the training that all staff should receive. Santa Fe also requires all of its new hires — both certified and non-teaching staff — to complete the active shooter training using materials developed by the I Love You Guys Foundation.

“When teachers get their degrees and certification, they still have not received training about safety and security,” he said. “It’s not anyone’s fault, other than just where we are in education today as a result of incidents like May 18. But if they’re sincere about learning, they can understand how to react in an incident according to how we want them to react.”

While he understands why some are left uneasy by the district’s strong security measures, Espinoza noted that schools must continue to be diligent in an era that has seen mass shooting tragedies only increase.

“The shooter did this knowing there were two officers on that campus, and it didn’t stop him,” he said. “If it can happen in Santa Fe, in this district, it can happen anywhere.”

Coming Next: The Parent.

I'm proud of my nephew, for doing a great job of keeping schools safe and families in peace know ing that their children are being safe, my prayers to him and his staff may God giving him wisdom in all that he does May God protects everyone in Santa Fe District in Jesus name..

.

In light of Uvalde-and now again reading this- I am surprised that so many school districts in TX. have their own police forces, even smaller ones.

I'm neither for or against it (and I don't vote there, anyway), but it's interesting to me that Santa Fe voters voted no on a referendum on expansion, but are paying for what is essentially a 2nd police department in their town.