Flashback: Lou & Brian

A story about two conflicted souls and the effect they had on my life

This essay was first published after the 2013 death of Lou Reed, who is back in the public eye thanks to Todd Haynes’ fantastic documentary on “The Velvet Underground,” now on Apple TV+. I read back through it for the first time recently and decided to republish it (with minor edits) here.

I can’t put a finger exactly on when I became a Lou Reed admirer — fan is a word he alternately would have loathed and loved. But I think he would have appreciated that I came to love his music — or at least a great deal of it — in backward fashion.

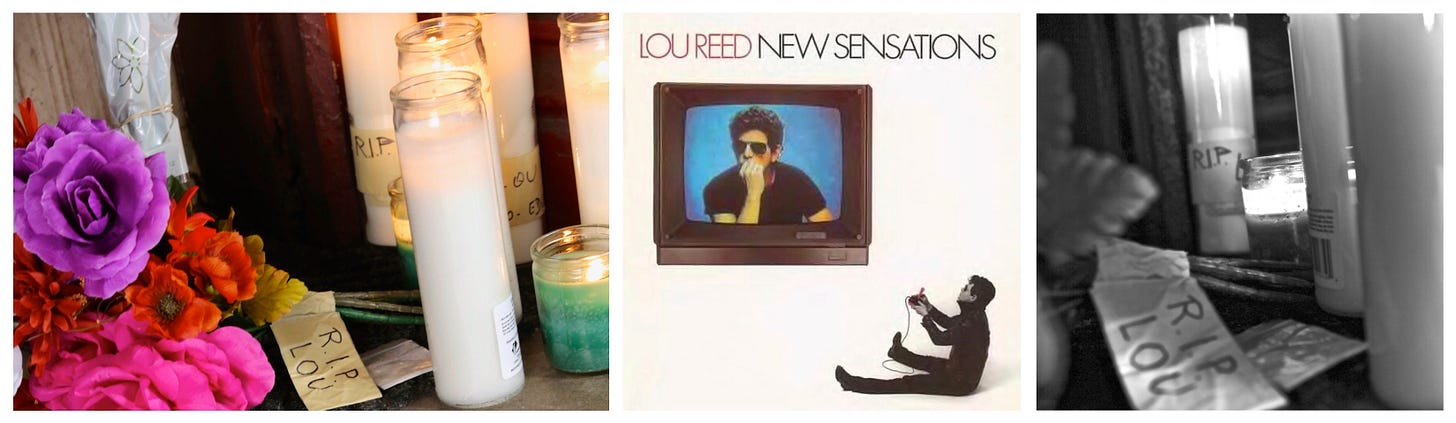

My appreciation started, I guess, when a neighbor passed me “New Sensations” in the late 1980s. At the time, I was living in Houston’s museum district, an area that opened my eyes in ways my parents had always feared. It was my own sort of quiet rebellion; I was partially embracing a bohemian lifestyle while working nights and going to school during the day, unsure of what the next chapter would bring.

Reed’s music — along with that of X, The Clash, R.E.M., the Talking Heads and, somewhat belatedly, The Replacements — pointed me in directions that clashed with the reality I experienced growing up. They are directions I continue to find intriguing and exciting, especially from a distance. To this day, I can still quote Reed’s 1989 album “New York” verbatim and find myself looking for the very characters he describes when I walk the city’s streets.

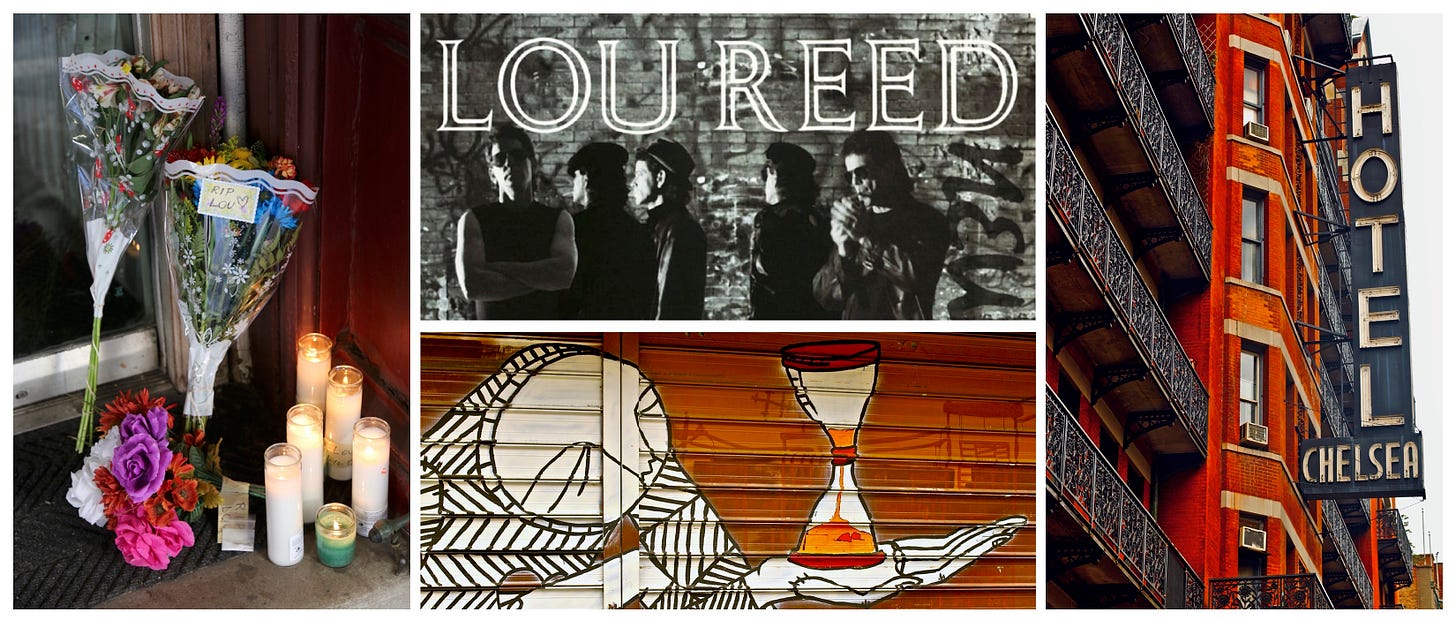

In October 2013, I was in New York the day after Reed died of liver failure at age 71, and found a minute to walk to the Chelsea Hotel, where a makeshift memorial with candles, flowers and notes was placed at the entrance. Someone also put a small plastic Ziploc with a powdery substance inside. While I stood there, a woman walked to the memorial and moved it out of sight. Another passerby said, “He wouldn’t have cared.”

Two doors from the Chelsea, painters were finishing work on the sign for a new 7-11 that will open on West 24th Street. On that note, I get the feeling Reed would have cared. Or maybe not. I’m not sure.

My first exposure to Reed’s music came the summer before my freshman year in college, when I picked up and consumed Edie, the biography of socialite and Andy Warhol muse Edie Sedgwick. Masterfully presented in an oral history format by Jules Stein and editor George Plimpton, Sedgwick’s story is part of the bigger tale that was New York in the mid to late 1960s.

For a brief period, Sedgwick was the brightest star of Warhol’s faux reality show, inspiring Bob Dylan to write “Just Like a Woman.” But within five years, she was dead of a drug overdose at age 28.

She never stood a chance, given the Warhol-level indulgences and the Sedgwick family tree — a generationally unstable lineage with a history of great wealth, mental illness, breakdowns, and suicide.

At the time, I did not understand why someone with so much would piss it all away in a drug- and alcohol-induced haze. Thirty years after reading the book, I still have trouble reconciling her path toward self-destruction, although I’m more understanding than ever of how fragile life — especially with a deep family history of mental illness — can be.

Just after finishing Edie, I met and quickly became good friends with Brian, a fellow student at the University of Houston. I didn’t have many male friends growing up, but we formed a bond that lasted more than 20 years. He was like the older brother I never had.

When we met during my freshman year, Brian was a sportswriter at the university newspaper, an erstwhile English major on the slowest possible path to graduation. He was putting his life on the right path, he said, claiming he could not remember his last three years of high school because he was stoned all the time. Going back to school at 23, he said, was a chance to make something of his life.

Brian and I bonded over sports, music, movies, and journalism. He handed me my first copy of the Village Voice and extolled the virtues of the alternative press. Over time, I learned of the struggles he had growing up as the oldest child of alcoholic parents involved in a toxic, codependent relationship. Brian had identified his parents’ issues and tried to work his way through them, but life proved to be a constant struggle.

For a time, our lives paralleled. He married. I married. We participated in each other’s weddings. He had children. I had a child. Then I moved from Texas to North Carolina. The time between our conversations lengthened, buoyed occasionally when I returned to Texas and we managed to connect in person.

He did not understand why I left my first marriage, at least in the beginning. I did not understand why, if he was miserable in his relationship, he did not do the same. But Brian said he could not leave his children, no matter how many times he wished his parents had divorced when he was growing up.

After returning home from New York, I found a Fresh Air segment devoted to Reed’s life and legacy. The primary interview subject was Bill Bentley, who worked as his publicist from 1988 to 2004 — no easy task given the songwriter’s notoriously prickly nature.

The program, which featured clips of interviews with former band members and others close to Reed, was an intriguing listen. But one quote in particular stuck with me:

"Lou's whole contribution to rock 'n' roll was — at the very start of his career he said, 'You should be able to write about anything.' Anything you could read about in a book, or talk about in a play, he felt should be in a rock 'n' roll song,” Bentley said. “He set that out as his No. 1 goal: to change the parameters of what rock lyrics could be.”

And he succeeded. To the listener with a pop ear, much of his music can be tough sledding, although he wrote some cool pop songs. (I’m not a huge fan of feedback and extended drone, and “Metal Machine Music” is almost as bad to me as “Having Fun with Elvis on Stage,” for many of the same reasons.)

The riches for the reader, and occasionally the beauty, are found in the lyrics, three- to 10-minute short stories and poems filled with vivid characters living on the fringes, with tragedy lurking nearby.

Like his parents, Brian had a love-hate relationship with alcohol and depression. He fought his demons, but the demons fought back. Eventually, in 2005, he and his wife separated — apparently for good this time. He also took a leave of absence from his job.

No matter how many times I asked him to call if he needed help, I was always the one picking up the phone. In 2005, we talked only three times — once when I went back to Texas, and in two other conversations. The last one, in June one weekend evening when I was working late, seemed like old times as we talked about sports and music. The Houston Astros were making a run that eventually would land them in their first World Series, and now that I lived near Washington, D.C., we trash talked about the Redskins/Cowboys rivalry.

In early September, two weeks before the Redskins/Cowboys game on Monday night football, I called his office and was told he wasn’t there. I also called his apartment but got no answer.

On September 19, the Redskins won 14-13 on two huge plays and I thought about calling again. I was leaving for a meeting in Las Vegas that week and decided to wait. While I was in Vegas, I received a call from Sandra Santos, a mutual friend and former college classmate who told me the news.

Brian hadn’t seen the game. In fact, when I called his office that day, he had been dead for two weeks. He had taken his own life, apparently so miserable, tortured, and hopeless that he decided to leave his sons behind after all. His soon-to-be-ex had buried him with no obituary notice and no calls to his friends.

Apparently no one at his office knew what to say.

I’ve thought about Brian often since his death. Standing outside the Chelsea Hotel and its many ghosts, I felt his spirit more strongly than I have in years. Listening to the Fresh Air program, I felt it again and was reminded of Reed’s song “Perfect Day.”

It’s easy to be lulled into the lyrics at the start of the song, “Just a perfect day/drink Sangria in the park/And then later/when it gets dark, we go home … Oh, it's such a perfect day/I'm glad I spend it with you/Oh, such a perfect day/You just keep me hanging on.”

But then it turns dark: “Just a perfect day/you made me forget myself/I thought I was/someone else, someone good.” And even darker still with the refrain at the end: “You're going to reap just what you sow/You're going to reap just what you sow.”

I miss you, Brian. I hope somewhere you’re resting in peace. I hope Lou Reed is too.

Beautifully written, Glenn, and heart-wrenching. Wildly coincidentally, I also met a good friend at UH (in the late '70s, he was also a sportswriter/photog at The Daily Cougar)! I stayed in touch with over the decades, even when I moved to L.A. from '80-'93. By now, you may have read my piece on my days at KUHF in the mid-'70s.

So good was your writing here, you almost made me a "fan" of Lou Reed! About the only album I ever had of his was "MMM," which I'm stunned you mentioned! Of course, mine was a promo, but I was astounded at how audacious Lou was to "middle-finger" RCA with a two....count'em TWO record set of that noise! And, not to be out-done, RCA (did you notice THIS?) proceeded to release it under their classical music Red Seal imprint! I don't know who, exactly (Lou's fan base, classical fans?), but SOMEBODY had to be insulted!

Certainly, I'm aware of Lou's influence across rock, but as an acquired taste, he simply, for me, remains a sushi platter on the menu of rock. I HAVE been a longtime fan of Lou's buddy, Patti Smith, who, as I'm sure you know, writes on Substack, as well! Met her ever so briefly back in the day...enough time for her to sign my copy of her "Babel" book.

I enjoyed your Elvis article, too, and the introduction you gave us, into your family! Cheers!