'Wholetown'

The duality of the Southern thing: Living in a historic city near Washington, D.C.

In this edition of the Social Distancing Diary, here is a look back at a magazine-length story I wrote in June 2020 after an encounter in a park near our Alexandria, Va., home. The encounter, combined with protests over the death of George Floyd, prompted me to take a look the town where we live and its checkered history with race. Minor updates have been made to the essay for publication here.

When my wife Jill and I moved from North Carolina to Northern Virginia in 2001, Old Town Alexandria was the place we wanted to live even as we bought a house in the Fairfax County suburbs. As empty nesters, this was the first place we looked when we downsized. Owning a home in a place with roots dating back to George Washington sounded like a dream.

And it has been. We love our home. We love the walkability and not needing a second car. We enjoy the many restaurants and interesting activities just blocks away.

But we’ve also learned first-hand that Alexandria’s history is both its charm and its stain, an inherent duality tied to race and privilege.

Over the last four decades, the city’s leaders have wrestled with Alexandria’s past, acknowledged many of its sins, and worked hard to move forward. Even as it gentrifies rapidly, thanks to its proximity to Washington, D.C., the town has billed itself as one of the most progressive in the country.

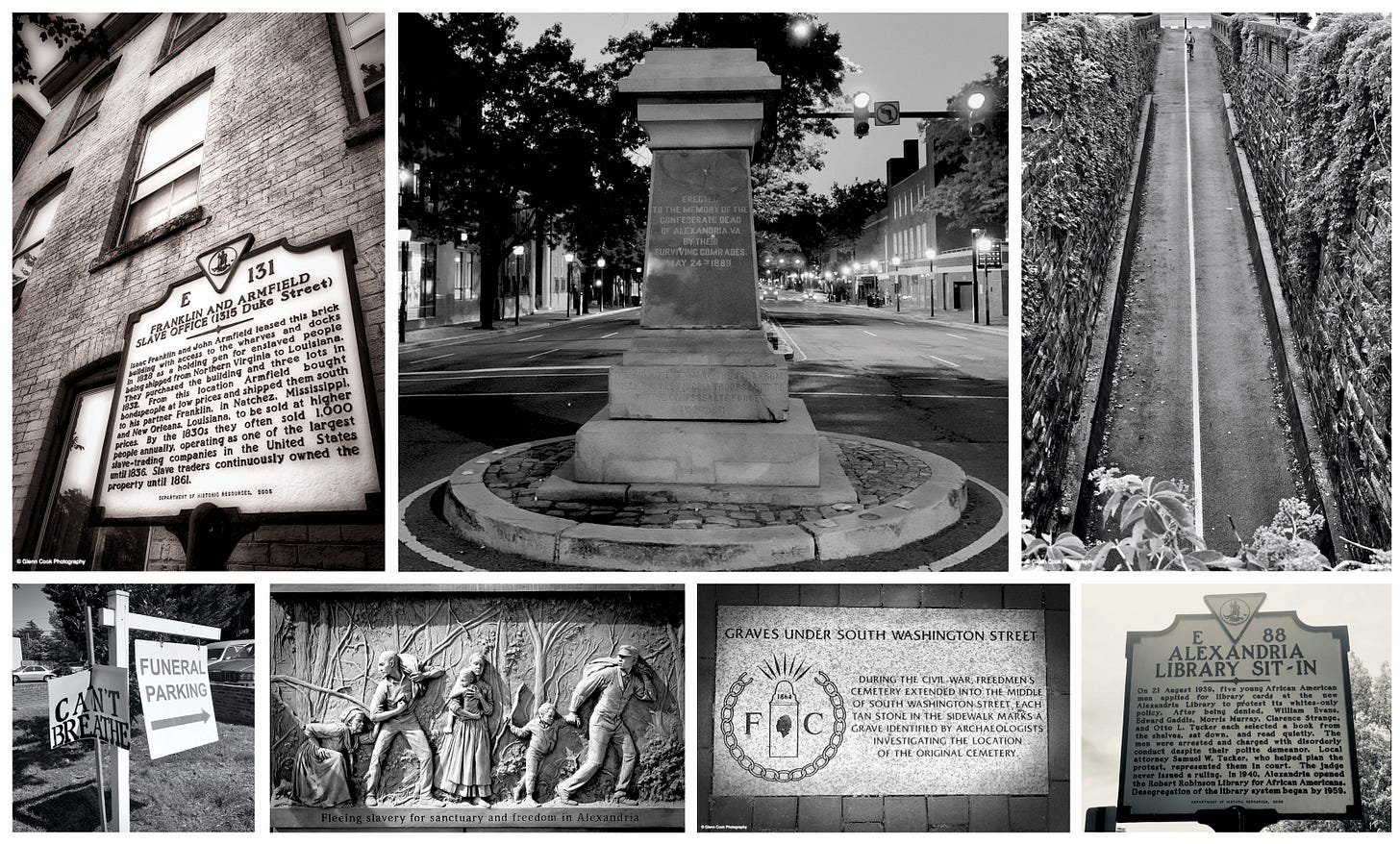

But until May 2020, when the murder of George Floyd reignited the Black Lives Matter movement and resulted in protests about race and equity, the Confederate statue remained in the center of town.

Appomattox, as it was known, was taken down in the middle of a quiet June morning.

A Walk in the Park

In June 2020, several weeks after Floyd’s murder, I started walking down King Street toward the Metro station that is about four blocks from our house. The station’s parking lot and bus area had been under construction since November 2018 and — in part due to the pandemic — no date for completing the work had been announced. It still has not been completed.

East of the station, in a triangular area that feeds into Old Town, is the King Street Gardens, a city park that opened amid the massive redevelopment of the area around the Metro. The park, which opened in 1997, features a large metal sculpture that hints at a colonial-style three cornered hat, a ship’s prow, or a plow. The sculpture serves as a trellis, providing some much-needed shade during the summer months for people who want to eat outdoors.

At one point, the small park hosted local farmer’s markets. But that went by the wayside before we moved here in 2018; as of this writing (June 30, 2020) a website about the park was last updated two years earlier. Once the Metro construction began, the park fell into disrepair and became a place where the homeless — men of color mostly, although you occasionally see a woman — congregate during the day and at night.

Walking to the park, I noticed a man setting up what appeared to be a collection of objects and trash. He had a series of crudely crafted signs placed on the different piles; one — “Wholetown Alexandria” — was taped to a pole under a “No Parking: Bus Stop” sign. I took a few pictures with my phone and spoke to the rail-thin man, who was homeless and living in the park.

His story, as he told it to me, is a bit of a jumble. Words spill out without a consistent narrative thread. The man spoke of growing up in a small house just down the road on King Street. He said he owned a small business at one point, then became a drug dealer, but threw thousands of dollars of drugs into the sewer and has remained clean since. He said he was kicked out of a shelter when he tried to report a sexual assault against him.

The man said he wanted to reunite with his daughter and railed against restaurants that throw away food rather than give it to him when “all I need is something to eat.” One of his signs touted “Free Drinks”; he said anything he received he would give away. He said the police are monitoring him but had not tried yet to make him leave. He refused to wear a mask but tells people to keep their distance.

I don’t know what pieces of his story are true. All I know is we acknowledged each other by name when we saw each other on the street several times during that week. New signs went up, although “Wholetown Alexandria” remained wrapped around the pole. When I stopped and asked how he’s doing, and the words came pouring out, as if instinctively he knew the conversation would be brief.

After a week, he told me his 7-year-old daughter stopped by with her mom, that he’s was trying to raise money to finish a doll house he found on the street to give her, that he was going to North Carolina to see his dad.

“I’m wrapping up here soon,” he says, pointing to scrapes and cuts on his legs. “This is no place to live. I thought about going down there to sell drugs and make some money, but I can’t do that if I want to see my daughter. And I want to go see my dad.

“He’s not my father, but he’s my dad. You know what I mean?”

I nod. We said goodbye and I continued on my walk.

A Town Filled With History

Located only a few miles from the nation’s capital, Alexandria dates back to the Colonial era; five blocks to the east from our house is the church that Washington attended. In the 18th and early 19th century, it was one of the busiest ports in America and home to the largest slave-trading firm in the country. When the Union took control of the city, Alexandria became a Civil War supply center for Union troops and was a safe haven for those escaping from slavery.

By the early 20th century, the city center — Old Town — was surrounded by a band of African American neighborhoods that included Uptown and The Burg. The neighborhood where we live now — known as Upper King Street — bumps up against the Parker-Gray Historic District that once was home to Uptown.

In 1939, five African Americans walked through the doors of the segregated Queen Street Library and staged a protest for library cards; it was the first peaceful sit-in in U.S. history. Thomas Chambliss Williams, the superintendent of the city’s schools from the 1930s to the 1960s, was an avowed segregationist who was part of Virginia’s mass resistance movement.

A high school was named after him.

A gas station and office building were built on the grounds of the Contrabands and Freeman Cemetery, where blacks who escaped slavery by any means necessary were buried in the 1860s. Part of Washington Street, the main thoroughfare between D.C. and Mount Vernon, covers a portion of the cemetery. Several blocks down, at the intersection of Washington and Duke Street, stood Appomattox, which was erected in 1889.

Since Floyd’s murder, the name of T.C. Williams High School has been changed, as has another school named after a Confederate hero. This is significant, in part because the 1971 T.C. Williams football team — made up of squads from three high schools that had been merged that year as part of integration — won the Virginia state championship under first year head coach Herman Boone, who was black. The story inspired the 2000 film “Remember the Titans,” which was a huge box office hit despite — or perhaps because of — its troubling if not tone-deaf fictional elements.

The backlash was swift as culture war debates and hyperpartisanship have consumed local and state officials as well as Congress. A cynic would say it’s yet another case of history repeating itself.

Learning from Experience

For many months, and to this day for some, the pandemic forced us to turn inward, both literally and figuratively. It gave many of us time, without the daily outside distractions that clutter our days, to think about how our actions affect others.

My wife and I have worked hard over a long period of time to build the life we have, and we consciously try to help others who are less fortunate. But, in this look inward, I realize more and more that what is happening is not about us. Ego and hubris, blanketed in privileges I didn’t recognize I had, made me think it was.

I’m working to be more empathetic, to listen, to understand, and ultimately, to do better. But no matter what I think, some things I will never know.

The question remains, “What are the next steps?” Despite the backlash, the taking down of memorials and changing the names of schools and public buildings was overdue. The moves also proved to be largely symbolic, a punishing of the past that so far has had the effect of kicking a fire-ant bed.

No question, protests can have an effect. Noise around issues that matter is good. But when protests fail to result in defined action, the noise just becomes noise, and eventually even it will recede into near silence.

That’s what is happening now. And it’s one reason the phrase “Wholetown” haunts me.

The entries serve as supplemental materials to my photo book — Keep Your Distance. Unless otherwise noted, the photos in this series are not part of the book.

To mark the pandemic’s fifth anniversary, these “Social Distancing Diary” installments will appear two to three times a month on Thursdays until March 2026. To see previous entries, visit this link.

Keep Your Distance: Walking Through the First Year of COVID is available for $40 plus $5.95 for shipping and handling. You can order it by visiting this link.