Brown at 70

As milestone approaches, looking back and ahead at K-12 school desegregation and the town where it all started

Two decades ago, I embarked on a project that has continued to shape and define much of the work I’ve done as a journalist: An in-depth look at the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court decision declaring that segregated schools were unconstitutional.

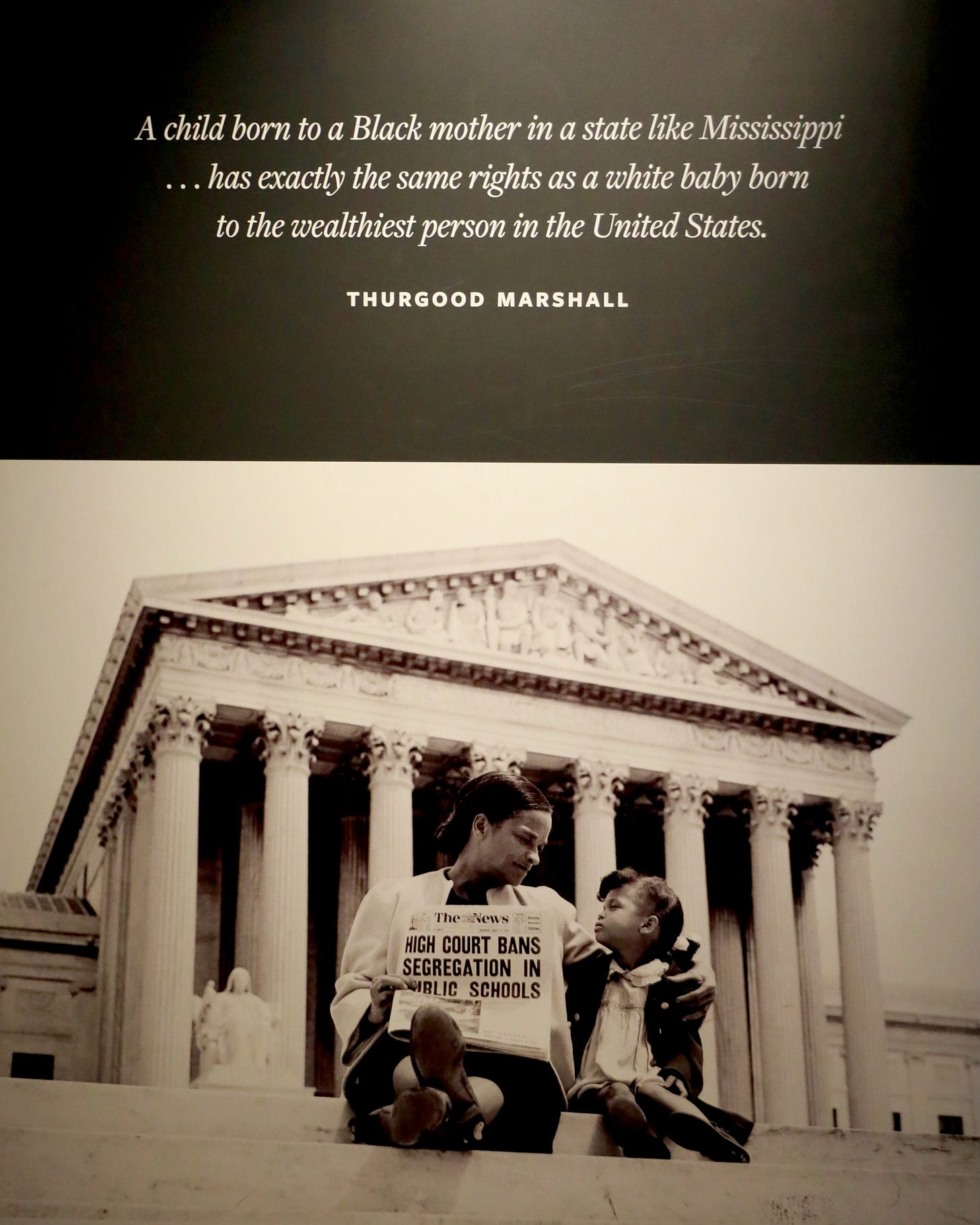

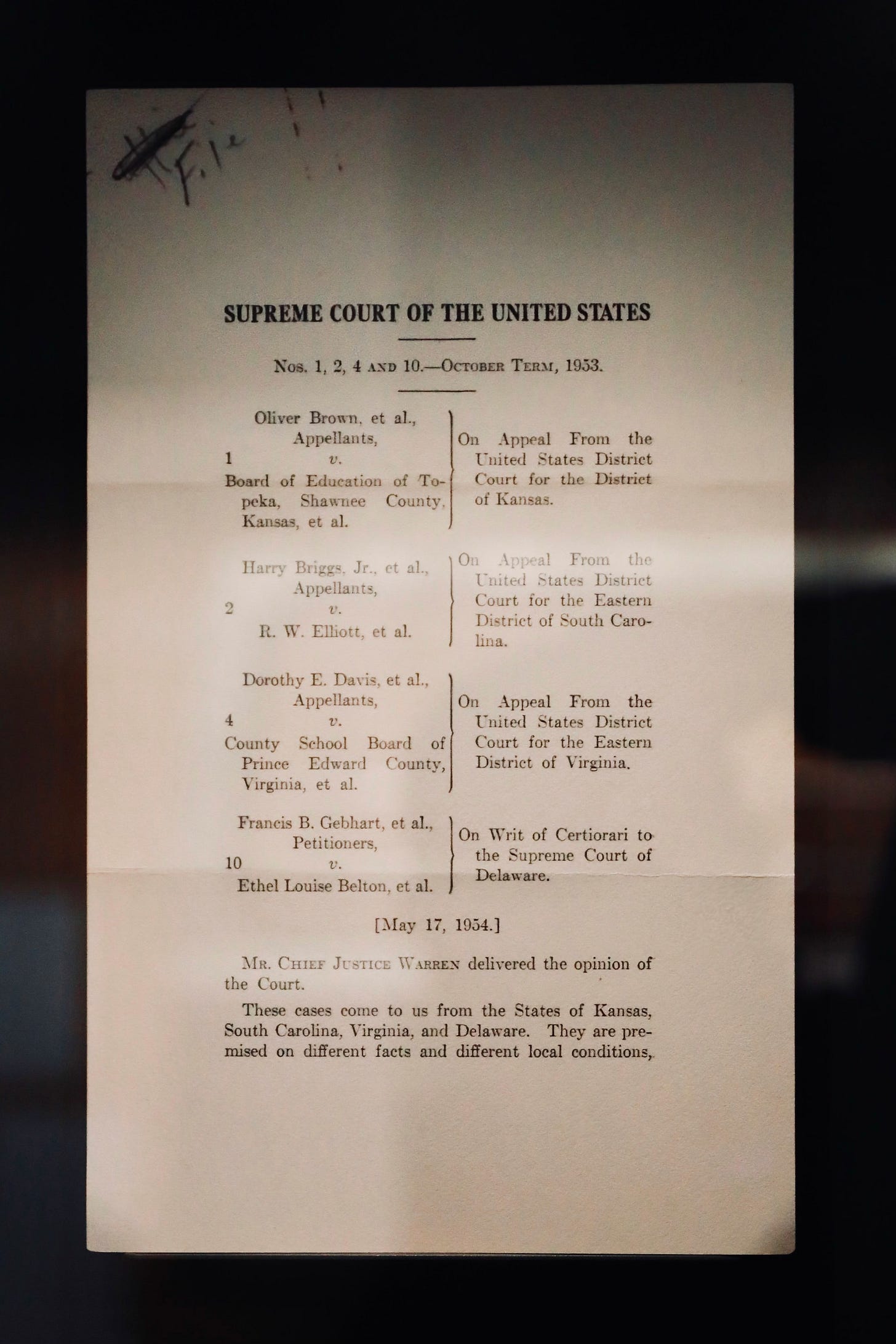

The unanimous ruling, issued on May 17, 1954, is one of the keystones of the Civil Rights Movement. It also is an ongoing reminder of how messy and ugly our nation’s history is despite often successful efforts to bury it through crafting a different and often whitewashed narrative.

Over the past several months, I’ve posted a dozen new, edited, and archived pieces — 11 of them mine; one from a dear friend and longtime professional colleague — on the Brown decision to my Substack site.

The stories are not the definitive tome on Brown or on Briggs v. Elliott, the Summerton, S.C., case that was the first of the five lawsuits that led to the landmark decision. However, they serve as a primer for anyone who wants to dig further into our nation’s history and as a reminder of what has been lost and gained over the past seven decades.

So why revisit this now?

As the 70th anniversary of the decision approaches, a series of developments have taken place nationwide and in Summerton — a small community about 65 miles from Columbia, the state capital — that make the Brown decision and what it represents extremely timely. Here is a look at what is occurring in the courts and in our schools nationwide, the story behind my reporting, and an update on what has taken place in Summerton since my last visit in 2019.

Why Briggs and Brown Still Matter

In many respects, as our nation’s politics have become more stratified, the divide caused by segregation never has gone away.

Starting in the 1990s but especially since a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court ruling struck down two race and equity initiatives in Seattle Public Schools, K-12 campuses are as segregated racially, by ethnicity, and economically as they were before Brown, researchers note. Additional concerns about K-12 equity initiatives also have been raised since the Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions in June 2023.

Research has shown that students in diverse schools have better academic performance than those who are in low-income Title I schools. Low income and minority students are less likely than their wealthier and white peers to be prepared for college or career success, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Meanwhile, our country’s changing demographics also are resulting in more segregation. According to a 2022 report by the National Center for Education Statistics, minority student enrollment has continued to grow in public schools, which now are majority nonwhite. At the same time, 18.5 million students — more than one-third of the total enrollment in the U.S. — attend schools in which 75 percent or more identify as a single race or ethnicity.

And over the past five years, the subjects of race and equity have become flashpoints in school districts that are in the crosshairs of conservative lawmakers, activists, and parents.

“The great promise of Brown was one of equal access to high-quality education,” Alexandra Filindra, author of Race, Rights, and Rifles, wrote in an op-ed for The Hechinger Report. “The hope was that income and other social disparities among white, Black, and Latino people would dissipate over time. White resistance contributed to America not keeping this promise.”

Origins

The seeds of my work on Briggs and Brown were planted during a late-night conversation with Cecile Holmes, who I first met when she was named religion editor at the Houston Chronicle in 1987. Even though we worked together at the Chronicle for only 18 months, we became lifelong close friends and talked often about collaborating on a project.

In 2003, I was the managing editor for American School Board Journal, the oldest continuously published magazine in the U.S. Then in its 112th year of publishing, the magazine was in a unique place because it was editorially independent of its owner, the National School Boards Association. That meant we had the discretion to pursue and write articles that would be of benefit to our readers without serving as a house organ for the organization.

Cecile, who returned to her native Columbia in 2000 to teach in the University of South Carolina’s journalism department, had just created a semester-long course called “Faith, Values & the Mass Media.” She had long been interested in the role of ministers and civic virtue in the Civil Rights Movement. When Summerton and Briggs came up during that late night call, we recognized that we had a chance to work together again.

We pitched a series of stories to my editor and publisher that also would involve her journalism students, who in turn would craft their own pieces about Briggs and Brown for USC’s student journalism and for NSBA’s magazine. For seven months, I made multiple trips to Columbia — sleeping in the spare bedroom at the home of Cecile and her husband, Jace — and to Summerton to work on the story that became “From First to Footnote.”

For the story and other pieces that appeared in the magazine, I also traveled to Charlotte, N.C., and Farmville, Va., and conducted interviews with key figures from the time. Cecile, meanwhile, worked on a story for ASBJ titled “Putting Faith into Action” and shepherded her students’ coverage.

Over time, we started to unpack and understand the community of Summerton as well as the education system that was at the heart of Briggs v. Elliott. Our stories, which appeared in a 50-page special edition of the magazine, were well received by readers. McGraw-Hiil, one of the largest education publishers in America, paid for reprints of the magazine that were sent to every school district in the nation.

More important, many of the people we interviewed with Summerton ties — almost all of whom were connected to the Briggs v. Elliott lawsuit in some way — felt like their stories were finally being told.

Back to Summerton

In the winter of 2019, as the 65th anniversary approached, I returned to Summerton to see what had changed in the previous 15 years. The answer, as chronicled in a story titled “Segregation’s Legacy,” was “very little.”

That second story, and my friendship with Cecile, led me back to USC in the summer of 2019, where I spent a week as a visiting professor. I worked with senior journalism students, focusing on the topics of resilience and compassionate reporting and storytelling. Summerton and its struggles before and after Briggs were a large part of our discussions.

In 2019, Cecile and I again talked about writing a book — separately or together — about Briggs and its history. Work, conflicting schedules, and her health struggles that started in and around COVID made that impossible, and she passed away in 2022.

After Cecile’s death and knowing the Supreme Court would likely overturn the legality of race-based admissions in universities, I dug out my 20-year-old notes last year and decided to revisit the stories and interviews. In many respects, the work we had done then is just as relevant today, but most of it is no longer online. Several people I spoke with for those original stories are no longer alive; many of those still living now are in their late 80s and early 90s, and a number of them are in poor health.

As the son of a history teacher, I didn’t want to see those voices lost. And as I started looking back, the opportunity for new interviews presented themselves. Ultimately, I added two to this series. One is with author Rachel Louise Martin, who had written a book on the integration of the first high school in the Deep South post Brown. The second is with civil rights photographer Cecil Williams, who captured many key photos in Summerton as a teenager.

While I’ve not been back to Summerton since 2019, I’ve continued to follow what has taken place there. After decades of neglect and indifference about Briggs v. Elliott, this small town that was divided further by the construction of Interstate 95 has started to embrace its history.

Summerton Today

What changed? The exact reason is unknown, but the passage of time and and the opportunity to capitalize economically on that history can’t be denied. Clarendon County’s population is declining, and Summerton — an agricultural town of 800 near Lake Marion — has no major industry.

An active Summerton Community Action Group is credited with the 2021 placement of three historical markers in the town related to the case. The markers are outside St. Mark AME Church, the Briggs family home, and the home of Levi Pearson, who filed the first NAACP-supported lawsuit for equal transportation in schools. Prior to 2021, the only marker was at Liberty Hill AME Church that many of the Briggs plaintiffs attended.

In 2022, the predominantly African-American town elected its first Black mayor — Tony Junious, a Summerton native who served on the Clarendon County No. 1 school board. Clarendon County had long been served by three separate school districts — No. 1 was in Summerton — but they were formally consolidated in 2022-23 after receiving $40 million in financial incentives for facilities from the state.

Also in 2022, President Biden signed legislation that makes the former Summerton High School and Scott’s Branch High School part of the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Park. In Topeka, Kan., the former elementary school that Linda Brown attended was renovated by the National Parks Service for $11 million; officials believe a similar project in Summerton would be a boon to the town’s economy.

Following the signing, monuments recognizing the Rev. J.A. DeLaine, Harry Briggs, and other key figures as well as the petitioners were dedicated at Scott’s Branch High School.

Finally, in November 2023, a petition was filed with the U.S. Supreme Court to rename the Brown decision after Briggs, arguing that the case should be recognized as first rather than the footnote it became. Attorneys and advocates for the change, including civil rights photographer Cecil Williams and Briggs’ son Nathaniel, admit that it was a long shot, but they point to the original plaintiffs and note they overcame enormous odds, too.

“There’s a cost of being first, and we’re here today to talk about that cost and to reclaim this place in history,” attorney Thomas Mullikin said at a Nov. 7 press conference. “This isn’t about Democrat or Republican, Black or white, this is about equal opportunity for education in a rural state like ours.”

When I interviewed Williams last year, he noted the Supreme Court had never renamed an already decided case.

“If this country is going to ever reconcile with its history, this is a good time to do it,” Williams said at the time. “Because this was the epitome of a hijacking of the legacy, the history, and the heritage of a group of people.”

On Jan. 8, the court declined, without comment, to discuss the name change.