History Lessons

Why learning from our past makes me worry that we're doomed to repeat it

Last night, I made a brief stop at my favorite close-to-home watering hole and found myself in a conversation no one wants to have these days: Talking politics.

I’m a firm believer that two things can happen when you have one of these discussions with a person you don’t know well. Either an argument will begin, or the room will start smelling like someone has a bad case of irritable bowel syndrome.

Fortunately, the person asking if I planned to watch the GOP presidential debate is someone I know and have talked with on multiple occasions over the past few years. I knew from previous conversations that he self-identifies as a conservative leaning moderate and his question seemed to come from a place of genuine curiosity.

That’s the only reason I didn’t put “Hell” before “No.”

I also recognize that these types of questions are likely to increase between now and next November, and like many people, I’m uneasy about the choices we’ll have to make when the next election cycle ramps up. But I also know what I believe. I can’t vote in good conscience for anyone who intentionally seeks to harm others.

Although I’ve joked before that my political views were shaped by Saturday night television (RIP, Norman Lear), they also were formed by learning more about our nation’s history and what people will do to hold onto the power they have — perceived or otherwise — over others.

And it started with a childhood interest in U.S. history.

The Social Studies Maze

When I reached middle school, I did not understand why the social studies curriculum was taught the way it was.

Sixth grade World History was an “overview and introduction” — think Caveman (!) to Pyramids (!) to Columbus (!). In seventh grade, it was Texas history — the Alamo (!), Sam Houston (!), the oil boom (!), and football (!!). The last one was optional, unless your teacher also was a coach just trying to eke out a living.

Eighth grade brought early U.S. history, with a quick review of Columbus’ disdain for flat earthers, followed by a race from the Mayflower to the Declaration of Independence/Revolutionary War to First Industrial Revolution to the War of 1812 to Lewis and Clark before ending with the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865. Lots of wars there, with the predominant narrative being that they were caused by folks threatening our right to freedom and prosperity.

In high school, you had World History (Round 2) and World Geography in grades 9 and 10, followed by the second half of American History, which started with a brief mention of Reconstruction and then burrowed into the Second Industrial Revolution of the 1880s.

I remember asking my father, who taught middle school history for the last two-thirds of his career, why the almost 20-year gap existed between the two U.S. courses. At first, his explanation that there was too much material made sense, because cramming centuries into a nine-month class provides the substance of a TikTok video.

But when I pressed the matter further, noting also that our classes largely glossed over the recent history of the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, my mostly conservative but reasonably open-minded Republican dad gave me a knowing look while largely ducking the question. He did mention the two “Roots” miniseries — both huge hits at the time — and noted they also largely skipped over Reconstruction. (The first ends in 1870; the second picks up in 1882.)

If I wanted to truly understand what took place between the end of the Civil War and the Second Industrial Revolution, he said, I needed to start digging. So, I opened up my trusty book on presidential elections, The Glorious Burden, and began the journey. Before too long, I started to understand why social studies was taught the way it was 40 years ago.

Sadly, I also started to learn why so many still are fighting to keep it that way.

‘It’s about the kids.’

Every time I hear a state legislator, governor, or member of Congress use that phrase, no matter how well intentioned, I find myself suppressing (at best) an expletive or (at worst) a scream. The same goes for “thoughts and prayers,” a once innocuous phrase that has become a cliched trope, code for “We’re sorry it happened, but we’re not going to do a damn thing about it.”.

It’s not about the kids. For lawmakers, it’s about holding onto power, and in places where the politics have become more extreme, it’s playground bully behavior straight from the pulpit of urine, vinegar, and shame.

Say what you will, but the strongarm tactics of the playground bullies are coordinated and are proving effective. Pre-2017, Democrats naively thought they had finally eradicated the fire ant beds of intolerance, only to realize the fire ants got together with the cockroaches and formed a Super-PAC that only inflamed the culture wars.

Instead of civility, today we’re confronted by the either-or. “If I decide to speak to you in an unprofessional, socially ‘debatable’ way using profanity and at best questionable word choices, then it’s discourse. If you call me on it, then that’s censorship.”

Earlier this year, the Washington Post released “How to Rig an Election: The Racist History of the 1876 Vote.” The animated seven-minute short film, narrated by Tom Hanks, describes the little known or misunderstood moment that ensured racism and white supremacy would remain dominant across the South.

I watched the short after a friend sent it to me on Easter Sunday, and flashed back to the conversation with my dad. That’s what prompted me to start revisiting the stories I had written about Briggs v. Elliott, the first of the five cases that led to Brown v. Board of Education. (With the 70th anniversary occurring in May 2024, I’ve republished many of those stories/interviews and added a new one here on Substack. Two more interviews — one from 2004 and another from earlier this year — and an update will be added soon.)

The reporting on Briggs and the stories I’ve done on the school shooting in Santa Fe, Texas, have impacted me more than any other projects I’ve worked on in my four-decade career. Briggs provided insight into a world that I knew existed but knew little about; Santa Fe was a world I knew that had been shattered by senseless violence.

On Tuesday, a Texas man killed six and injured three others (including two police officers) in a series of shootings in San Antonio and Austin. That marks the 39th shooting this year alone in which four or more people were killed, the most in any year since 2006, according to the Post, and it came two days after weekend mass shootings in Dallas and Washington state set this grim record.

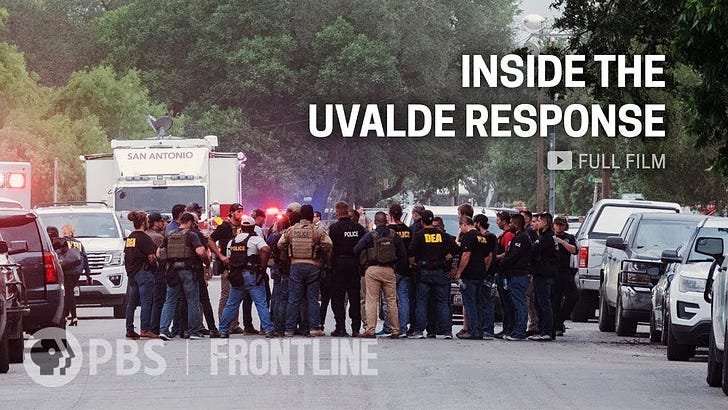

While everyone is quick to decry this violence, the solutions we seek vary greatly. Instead of watching strident presidential want-to-bes debating culture war issues, I wish people instead would take the time to view the documentary Inside the Uvalde Response. It aired last night and was developed by PBS’ Frontline, ProPublica, and the Texas Tribune.

It will break your heart, even if it doesn’t change your mind.

I'm pretty sure my history curriculum mirrored yours (with a little extra emphasis on Lewis & Clark and the Oregon Trail).

You and I think alike. thank you for sharing