Jason Isbell & The Last Waltz

How a 1970s documentary led me to the best damn songwriter today

One afternoon, on an early 1980s day, I walked into my parents’ house after school and found my grandmother sitting on the couch. She was watching a movie on HBO, a relatively new service at the time and the first premium channel on this thing they called cable TV.

When I asked what she was doing sitting there so riveted at 3:30 p.m. on a random Thursday, I was promptly “Shhh … ed.”

“Be quiet,” my grandmother — by this point in her late 70s — said. “Caravan is coming on next.”

Soon after, Van Morrison sauntered onto the stage and performed his classic song, which my grandmother swayed to on the couch before turning and asking, “Do you want to watch the rest of this with me?”

Who was I to resist “The Last Waltz,” a film considered to be the ultimate music documentary, an exercise in 1970s coked-up narcissism, or both? (It depends on your view.)

What I didn’t realize at the time was Martin Scorsese’s film, which proved to be the last gasp for the original members of The Band, would shape much of my adult taste in music.

The rise of Jason Isbell

Years ago, Steve Earle had an infamous quote: “Townes Van Zandt is the best damn songwriter in the world, and I’ll stand on Bob Dylan’s coffee table in my boots and say that.”

I don’t own cowboy boots, and I don’t know where any of Mr. Dylan’s coffee tables are (assuming he has several), but I respectfully disagree with Mr. Earle. In my view, Jason Isbell is the best damn songwriter in the world right now, as evidenced by “Weathervanes,” his ninth studio album released last month, and by the shows he’s currently performing with an expanded 400 Unit.

Earlier this month, Isbell and his band made their annual summer pilgrimage to Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, where they devoted almost half of the 19-song set to “Weathervanes.” Four of the concert’s first five songs — “Save the World,” “King of Oklahoma,” “Death Wish,” and “Strawberry Woman” — and nine in all came from the new album, which Isbell produced himself after ending a long partnership with Dave Cobb.

Isbell has said in interviews that he wanted a record that captured the 400 Unit’s live sound, which leans more toward rock than country. His blend of storytelling, mixed with music that stretches and bends acoustic and electric styles, is both familiar and yet revelatory in the tales he tells.

2023 has been a huge year for the Alabama-raised singer-songwriter, who first came to prominence with the Drive-by Truckers, a band he joined at age 21. Now a decade-plus sober, with several Grammys to his credit, the 44-year-old is known for his rigorous honesty and candor in his songwriting, personal life, and activism.

In addition to “Weathervanes,” one of the year’s most critically acclaimed albums, Isbell also has been the subject of the HBO documentary “Running with Our Eyes Closed” that was released in April. In September, he marks the 10th anniversary of “Southeastern” — his first post rehab album — with a new box set that was announced last week. (Isbell alluded to “some special things” coming up to mark the occasion during the Wolf Trap show.)

Like many, I first became an admirer of his songwriting and guitar work during his time with the Truckers, who re-released an expanded version of 2004’s “The Dirty South” — Isbell’s second and best album with the group — earlier this year. Having placed two early classics on his DBT debut — “Outfit” and “Decoration Day” — Isbell wrote four of the 14 tracks on the original “The Dirty South.” (A fifth, “TVA,” is included on the expanded edition.)

“Danko/Manuel,” one of Isbell’s songs on “The Dirty South,” was partly a tribute to Richard Manuel and Rick Danko, the first two members of The Band to die following the group’s initial dissolution. Manuel, one of the group’s co-vocalists, died by suicide in 1986 while on a reunion tour with three of The Band’s original four members: bass player Danko, drummer and co-vocalist Levon Helm, and keyboard master Garth Hudson. Danko died in 1999.

In the liner notes to “The Dirty South,” Isbell said he started writing “Danko/Manuel” in an attempt to capture Helm’s feelings about the “deaths and lives” of the two musicians. “The longer I worked on the song, the more impossible that became,” Isbell said. “I felt like the best I could do was to explain my own attitude toward being a working and traveling musician. The horn parts came to me in a dream.”

Helm died in 2012. Robbie Robertson — the group’s principal songwriter — passed away this past week, leaving Hudson as the last man standing.

Songwriting and Storytelling

On that afternoon more than 40 years ago, I sat next to my grandmother and realized she had seen “The Last Waltz” more than once, probably during one of its multiple airings on HBO. That she knew the movie should not have been a surprise; Grandmama had varied tastes in all kinds of music and had introduced my father to Elvis Presley in the mid 1950s.

What I always appreciated about Vera Cook was her openness to all types of music — religious, secular, country, folk, blues, and even rock. She told me more than once that popular music — and that which was not designed for the masses — were reflections of culture, place, and time, one that connects your present and past and can project what will happen in your future.

“I don’t have to like it,” she said on another afternoon when I caught her checking out MTV in its nascent days. “But I won’t know what I like unless I watch and listen.”

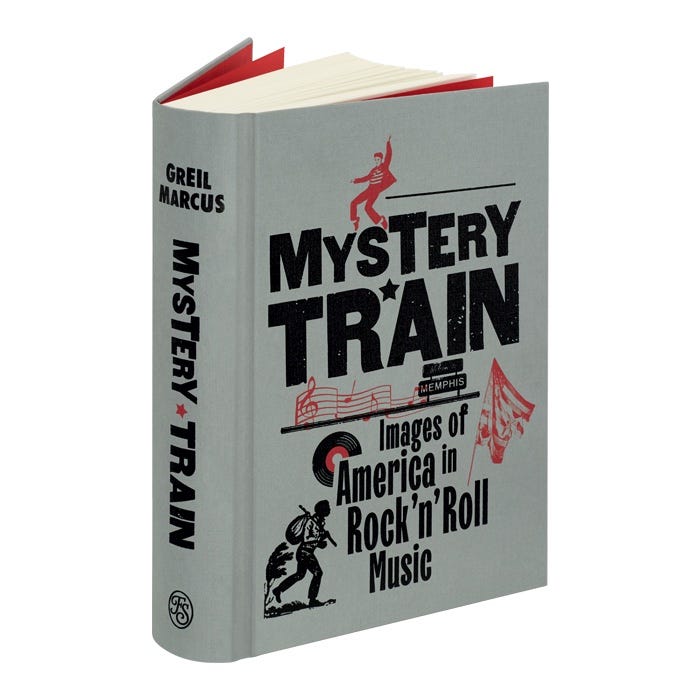

In high school, my music tastes started to broaden beyond the 45s and 33s that my dad had collected. Instead of sound, however, I found myself gravitating toward songwriters, the ones who could write a three-minute short story or a six-minute novel. Around this time, I also found Greil Marcus’ Mystery Train, a history lesson on the roots and culture of rock and roll and the throughline of music from past to present. After learning as much as I could about the presidents and football as a kid, music — and the musicians and groups profiled in Marcus’ book — became my new obsession.

One of those groups was The Band, which started as a rockabilly unit behind Ronnie Hawkins and then backed up Dylan on his first electric tour. After Dylan’s motorcycle accident, they gathered at Hudson’s “Big Pink” home Woodstock, N.Y., in early 1967 and recorded what became known as the infamous “Basement Tapes.”

If you’ve read this far, chances are you know the basics about the group. Back-to-back classic albums to start, with Robertson writing restrained and dignified storytelling classics (“The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “It Makes No Difference”) that flew in the face of the psychedelia and jam bands popular in the late 1960s. In many circles, The Band is credited as the forefathers of the genre now known as Americana.

The rest of the group’s studio efforts, with some exceptions, were mixed bags fueled by increased drug use. A road-weary Robertson decided to end the group’s touring days with a big party that became “The Last Waltz.” Robertson and Helm famously feuded over songwriting credit, in part because songwriters make all the money in publishing. Although The Band cut three albums after they reunited in 1983, it’s telling that their only classic from this era is a cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Atlantic City.”

After Isbell was fired by the Truckers in 2007, he formed the 400 Unit and released a series of solo efforts that were strong but uneven, with terrific gems scattered among songs that seemed unfinished or like sketches of ideas. Often at his early shows, he would perform “Danko/Manuel” followed by “Atlantic City.”

This Is It

“Southeastern,” which is on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, was a game changer for Isbell. Mostly acoustic, it featured a series of heartbreaking, painful and vividly drawn short stories (“Elephant,” “Stockholm,” “Traveling Alone,” and the lone full-band number, “Super 8”) put to song. Included in the collection was “Cover Me Up,” an instant classic detailing his decision to take control of his sobriety as well as his relationship with Amanda Shires, a frequent collaborator and terrific songwriter in her own right.

The Isbell-Shires relationship is at the forefront of Sam Jones’ HBO documentary, which chronicles the troubled making of 2020’s “Reunions.” Isbell was coming off of a series of acclaimed albums — 2015’s “Something More than Free” and 2017’s “The Nashville Sound” — and definitely was feeling a sense of self-inflicted pressure to keep going. The film, a fascinating warts-and-all documentary that matches Isbell’s songwriting honesty and candor, goes behind the scenes during the “Reunions” sessions while showing how his upbringing, time with the Truckers, and eventual sobriety have shaped his life, marriage, and songwriting.

Although “Reunions” has strong tracks, I found it difficult to embrace when it was released during the pandemic. I wasn’t sure why, but seeing the trouble Isbell and Shires were having at the time made it all make sense. (Shires’ musical response to that time, the album “Take It Like a Man,” was by contrast a remarkable statement of her own resilience and strength.) Since the documentary, I’ve come to appreciate “Reunions” more.

In 2021, Isbell produced “Georgia Blue,” a covers album he promised to make after the state voted Democratic in the previous year’s presidential election. Doing so gave him the confidence to produce “Weathervanes” himself, and it was a great move. Shires, now a solo artist in her own right and part of the supergroup The Highwomen, is no longer in the main credits but is listed as a guest on fewer than half the album’s tracks.

At Wolf Trap, you could tell that Isbell and his band — Shires guests on occasion, but no longer is a regular presence and wasn’t there — were having a great time performing the new songs live. Every member of the 400 Unit shined at points, especially core members Sadler Vaden, Derry DeBorja and Chad Gamble. Will Johnson (of Centromatic) on drums and guitar and fill-in bass player Dominic Davis (subbing for the missed Jimbo Hart) added muscle to the lineup.

DeBorja’s accordion during a lovely “Strawberry Woman” and keyboards on the heartbreaking “Elephant” — one of three songs from “Southeastern” — were perfect, quiet moments during an often raucous show. Vaden, alternating between electric, slide and acoustic guitar, received similar showcases on an extended, free-verse jazz-like jam version of “Last of My Kind” and on vocals during his crowd-favorite cover of Drivin’ ‘n Cryin’s “Honeysuckle Blue” (a track on “Georgia Blue”).

The show ended with “Cover Me Up,” the standard — in more ways than one — closer from “Southeastern.” It was followed by a three-song encore of “24 Frames,” “If We Were Vampires,” and “This Ain’t It,” perhaps my favorite track from “Weathervanes.”

Listening to the album on the day it dropped, I knew that had the potential to be the show closer, and “This Ain’t It” totally fit the bill. Weeks later, I continue to have the opening lyrics stuck in my head: “How did we end up here? / In a Texas town / In a wedding gown / With a near beer.”

The reason that reasonates is because, like many of Isbell’s best songs, I can imagine myself in a similar situation (sans the wedding gown, of course), disillusioned with life and the memories it brings. Instead, thanks to songwriters like Isbell, groups like The Band, and people like my grandmother, I have a life that I wouldn’t trade for anything. For someone who doesn’t dance, that’s the best kind of waltz.

I’m willing to stand on someone’s coffee table and say that, too.

Note: A portion of this essay was included in my review of Isbell’s concert for Americana Highways.

The Band & Isbell. Each has repeatedly brought me to tears. I'm glad your grandmother had such eclectic good taste (and the sense to listen to some crap as well). Thanks for sharing, as always!

Steve Earle wasn’t serious when he said Townes was better than Dylan, he said he just wanted to give him some recognition and publicity.