The summer before my freshman year in high school, our neighbor Fran hired me to do a job at her office — a 17,000-square-foot, two-story mansion located near NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

The position was offered on two conditions. First, Fran would pay me — minimum wage — out of her pocket. Second, I couldn’t talk about the task — color coding hundreds of thousands of photographs from space missions that Fran and a colleague had rescued from the NASA dumpsters.

Despite the secretive nature of the work, it was not sexy. But it is an interesting story.

Neighbors, NASA and Silver Dollar Jim

Ten years earlier, a month before Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon, we had moved into our house on 22nd Avenue in Texas City. Then 4 and looking for other kids to play with, I walked across the street and rang the doorbell at the Waranius’ house. Fran and her husband, Bill, had no children, but they invited me in for a visit, starting a lifelong friendship.

Fran and Bill, who were 10 years older than many parents, had moved to Texas from Chicago after he was hired by Amoco Chemical (now BP), one of the many petrochemical plants in my hometown. In 1970, the year after we arrived in the neighborhood, Fran started her job at the Lunar Science Institute.

Now the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), the research institution had opened earlier that year at the former mansion of “Silver Dollar” Jim West, a lumber magnate and oil man.

West built the 45-room Italian Renaissance Revival home in 1930 to serve as the centerpiece of his 30,000-acre ranch, which stretched from the banks of what is now Clear Lake to Ellington Field. Known for carrying silver dollars in his pocket and throwing them to people he saw on the street, West sold most of his property to Humble Oil (later Exxon-Mobil) in 1939 but kept the mansion. After his death in 1941, his widow moved to Houston, leaving the house behind.

Humble Oil developed the Clear Lake community and donated 1,000 acres to the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center (now JSC) in 1961. The West mansion, which had been left to Rice University with the provision that it never be used as a residence, sat vacant for more than two decades until it was renovated and opened as the research institute.

Coming on the heels of NASA’s first successful Apollo mission, the institute was established for scientists and academics from around the world to study space and the solar system. Fran became the institute’s first librarian in July 1971, making the commute from Texas City to Clear Lake in her Plymouth Duster.

Fran catalogued the library’s first book and more than 11,000 others during her 23-year career, but her greatest contribution started with a near dumpster dive.

Rescue Mission

By the mid 1970s, NASA was struggling financially. Federal funding, which had been accelerated throughout the 1960s in an effort to land on the moon, was cut under President Nixon. The final moon landing, Apollo 17, took place in 1972. Skylab, the first U.S. space station, was occupied for 24 weeks between 1973 and 1974. It wasn’t until 1981 that the first space shuttle was launched.

At one point, NASA contractors were told to toss the records from previous space missions that were housed at JSC’s Research Data Facility. Fran, an organized packrat who “never refused a file cabinet,” heard of the plan and convinced a NASA colleague to put them into her Duster instead of the dumpster.

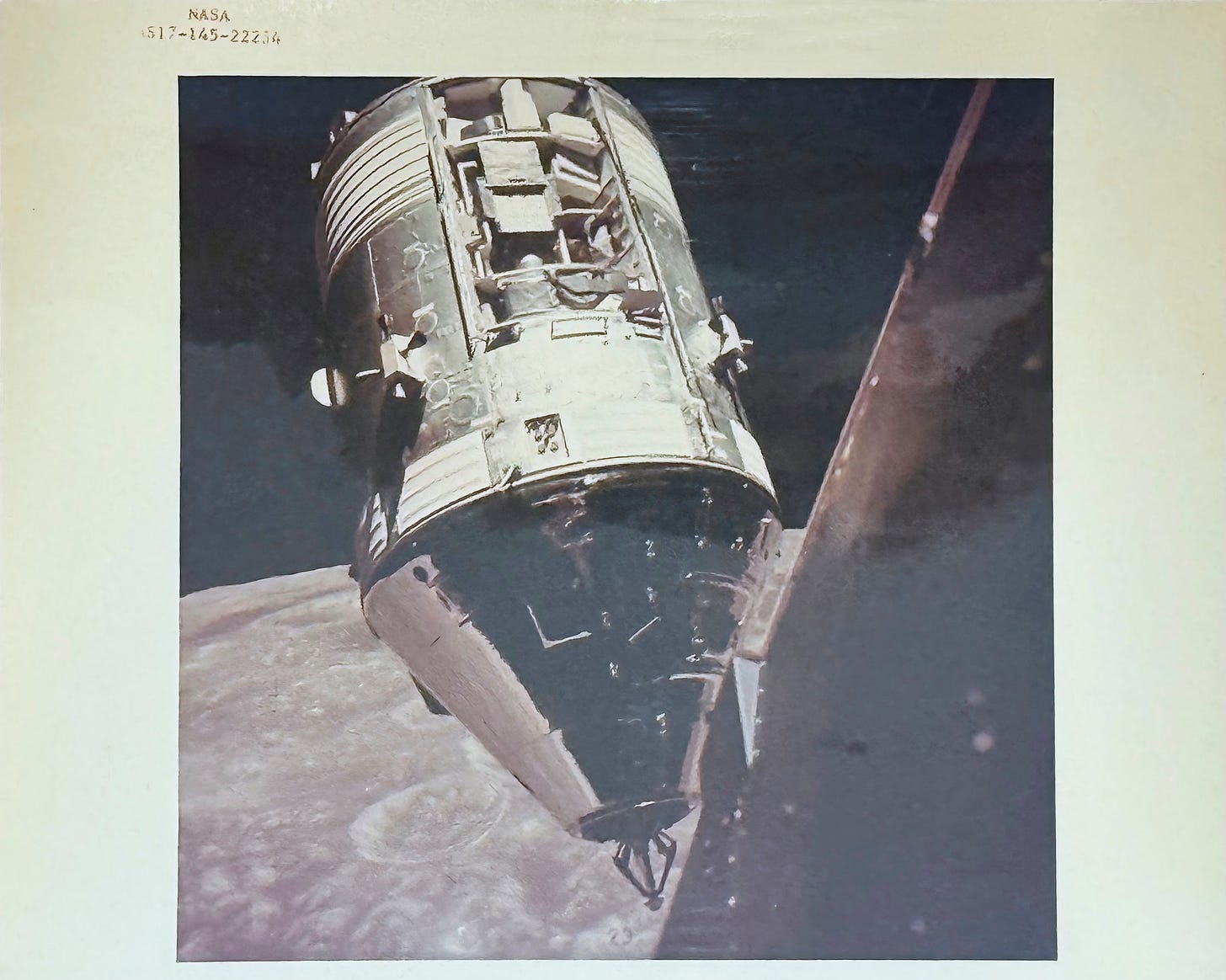

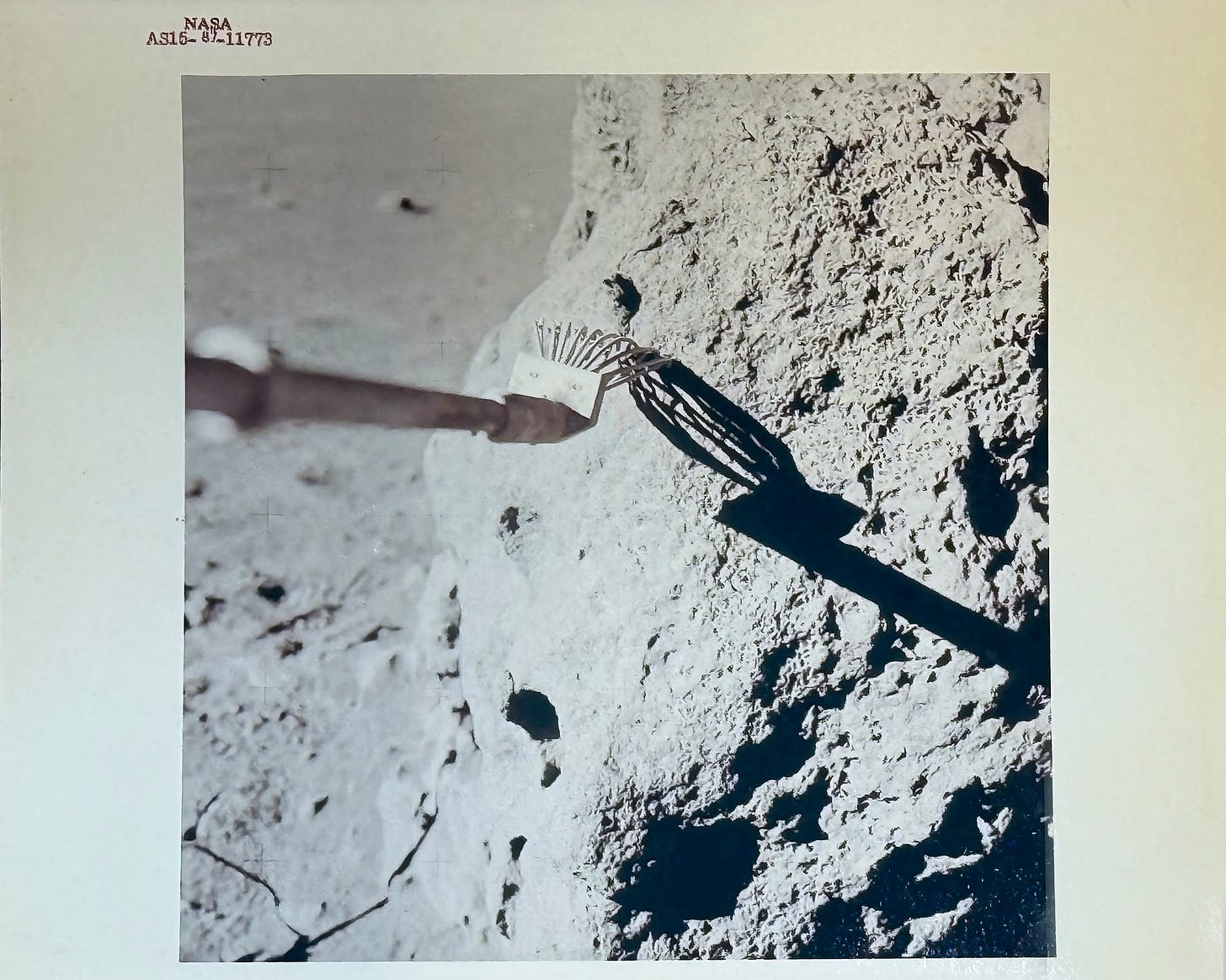

She moved photos and documents from the Ranger, Surveyor, Lunar Orbiter, and Apollo missions from NASA — most of them not digitized — into her house, where they stayed for six months. Eventually the lunar program materials were stashed in one of the multiple garages that West had built for his many automobiles.

"Sometimes it was rather clandestine. You kept what you had and kept quiet about it until you could convince people of the value of archiving it,” Fran said in an article that marked her retirement. “The collection of documentary materials. the early mission products — Surveyor, Ranger, Orbiter, even early Apollo — exist nowhere else.”

Fran had developed a color-coding system to tag the documents of each successful Apollo mission, which started with #7 in October 1968 and ended with #17 in December 1972. (The first Apollo crew — Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chafee — were killed in a flash fire during a simulation on the launch pad in Florida in January 1967.)

The problem: No one on staff had time to do the work.

Enter: Me.

Filing History

In the summer of 1979, I was 14 and in no man’s land when it came to possible employment. Already tired of mowing lawns in the smothering Texas humidity to get spending money, I was ineligible to work in a “real job” due to child labor laws that prevented businesses from hiring you until age 16.

I was born without a science gene, but Fran “hired” me to tag along with her to work, telling her supervisors that I was volunteering while she paid me under the table.

The task was organizing the photos, which had become jumbled in the various moves, into Fran’s very analog color-coding system. Armed with multiple reams of stickers, a cassette player, and six-packs of Tab, I took over an entire large garage for the project.

Countless boxes that held the photos were stashed in another garage, so I walked them over one by one to the room. I emptied each box, checked the serial numbers indicating which mission it was, added a sticker and built piles on two long tables.

For two months, five days a week, I looked at rock after rock, footprint after footprint, dusty surface after dusty surface. Occasionally, a classic image would appear out of nowhere and break up the monotony.

Out of order, I saw the history of our space program unfold.

The job had other benefits as well. On breaks, I wandered the hallways and grounds of the old West mansion. I spent valuable time in the car going back and forth from Texas City to Clear Lake with my “second mom.” Fran let me keep the duplicates of images I found and gave me additional NASA ephemera she had collected.

Afterward

Soon after my job was finished, LPI and NASA had a memorandum of understanding that established the institute as a repository for lunar program materials. Eventually, the archival materials Fran collected during her career filled 11 rooms in three buildings.

In 1992, LPI left the West mansion and moved to a more modern building near the University of Houston at Clear Lake. The following September, facing ongoing and worsening health problems from a lifelong battle with scleroderma, Fran retired.

She died in 2007, less than three years after her beloved husband.

The West mansion was sold multiple times over the next 25 years; the last owner was Hakeem Olajuwon, the Hall of Fame basketball player. Even though it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and designated a Texas Historic Landmark, the mansion was demolished by bulldozers in 2019.

Unlike the photos and documents saved by a packrat librarian, the mansion is a piece of history lost forever.

The images shown in this article are photographs of some NASA duplicates Fran allowed me to keep. Below are a few more:

What a wonderful story, and incredible photos. Thanks for sharing them!

Love it!! This must be the stuff you were telling Sarah and me about. What an amazing experience you had!