Turning the Tables, Part 2

Concluding the interview with Jeffrey James Higgins about my photo book, plus questions from the audience

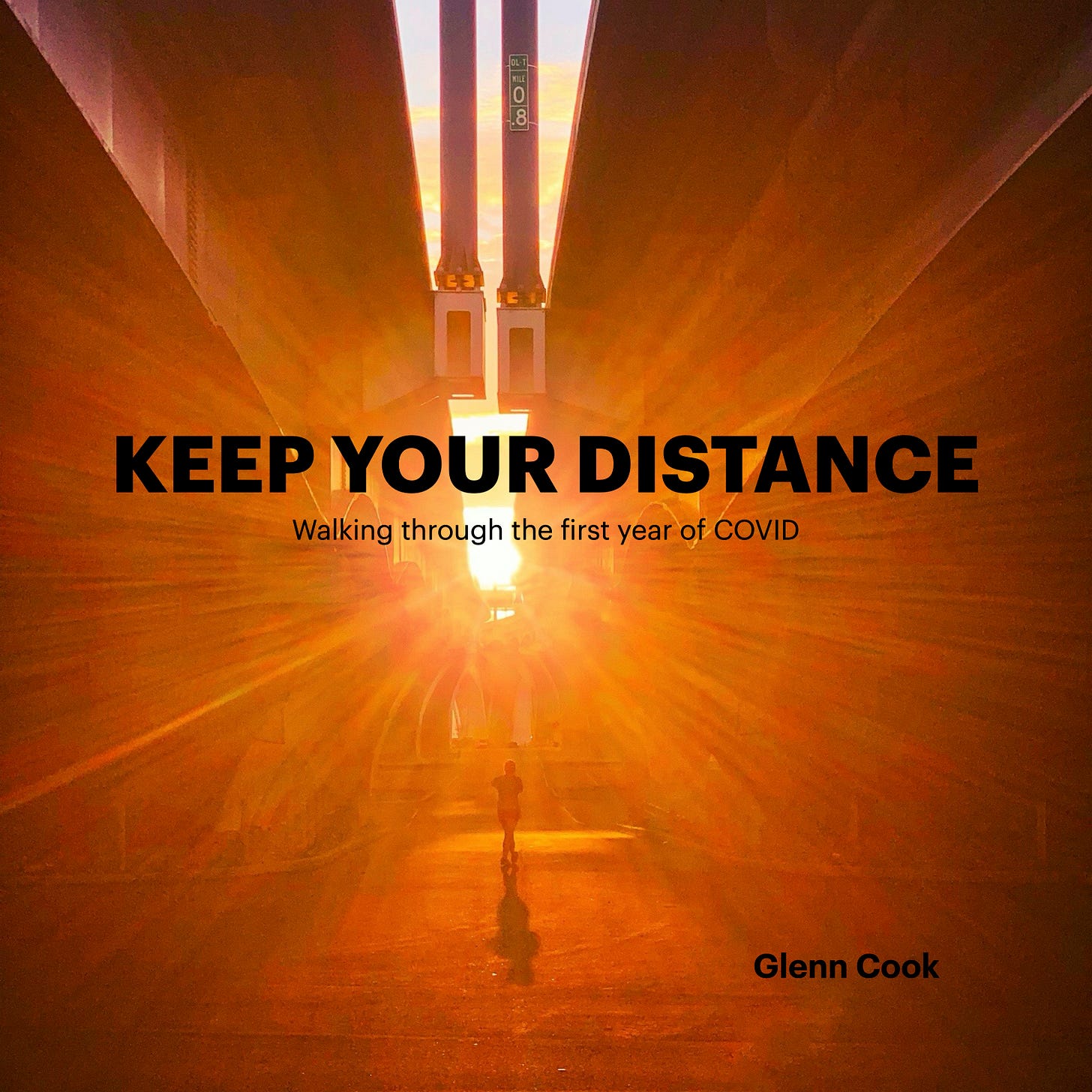

In the second part of my conversation with Alexandria author Jeffrey James Higgins about Keep Your Distance: Walking Through the First Year of COVID, from earlier this year, we talk about the creative process, self publishing and marketing a book, and how creativity is threatened by artificial intelligence. At the end, I also took questions from audience members.

As with Part 1, the questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Creative Process

Higgins: Which do you prefer, writing or taking photos?

Me: Both.

If you had to do one to make a living, which one would you give up?

Neither.

That wasn't an option, Glenn.

Honestly, it's truly about telling a story. And for me, writing and photography are so intermingled that I can’t separate them.

How much of storytelling is genetic? Are you born with this desire to tell a story, or is it something that you can teach anyone?

You can teach anyone to be mechanical about it. But I think that true storytelling, much like music, acting, or any art form, is innate. I photograph a lot of dancers, and I’ve seen some who were wonderful from a technical standpoint but watching them in performance is like watching paint dry. They can’t “tell the story” through their movement and expression.

The same applies to writing and photography. You can be technically proficient, but if you're not doing it in a way that moves somebody to emotion or action, then why are you doing it? That’s the goal of telling the story for me.

What do you get out of it? Do you enjoy the process, or do you enjoy it later when people are viewing it or reading it?

I enjoy the process because it’s innate, and it's something that I'm going to do no matter what, no matter who sees it. I don't care if anyone sees it. I'm going to do it because that’s what I do.

I think that's a mark of the true storyteller, by the way. They're going to do it regardless, even if no one ever reads it or sees it.

I write to process. I take photos to process. I’m about as ADD as they come, so one reason I like photography is because I can latch on to something, focus, and shoot it. When I'm writing and in “that zone,” I'm totally focused. For somebody for whom focus is elusive in every other walk of life, that's why I do it.

Is there a trick to get into that flow state when you're writing?

No. I wish. I've had times when I can write a thousand words in an hour. And I've had times when I can’t write a thousand words in a week. I spend the entire week writing and deleting, writing and deleting.

Sometimes the flow state is the pressure of an absolute, total deadline that can’t be missed or delayed any longer. Occasionally, the inspiration just hits, and when that happens you just ride the wave.

Self Publishing, Marketing, and AI

You self-published this. Did you consider going a traditional or hybrid route to get the book out?

Yes and no. One on hand, good luck getting a traditional publisher to look at anything. That’s just not how this works anymore for an author or photographer who is not “established.” And I looked at hybrid models, but I knew — and was told — that it was going to be a tough sell because it’s a book about a a year no one wants to remember.

I knew the commercial prospects for this were not great, but I also knew it needed to be published and the people who purchase it will get some benefit out of it. If you don't buy it, I'm going to be fine with that. What’s been interesting is getting feedback and responses from those who have.

I’ve now sold copies to people in 18 states and three countries, and the feedback has ranged from “That’s eerie” and “That’s a reminder of things I’ve forgotten” to “You captured my experiences too.”

Are you publishing a digital version too, or making it available on Amazon?

Yes. I have a paperback version that’s out on Amazon.

Obviously, any historical record of a traumatic event is important, but how do you go out there from the marketing side and try to get people to buy it?

I'm no different from anybody else who went through this, except that I chronicled it in images and words, and I want you to see what I saw and experienced. If you see what I experienced, and it causes you to reflect, think, and look at things from another point of view, then I’ve done my job.

We were talking earlier about the iPhone and how far it’s come. Are people — even professional photographers — still buying cameras?

Yes. The issue with any camera phone is they can’t really stop motion very well. They're better at that than they ever have been. They’re great for the grip and grin and for shooting “things,” but they’re not good at taking still photos of people in action. And the lenses are still limited.

This brings me to a larger point about technology and creativity. What I hate to see is the art being devalued. As a print journalist who worked for newspapers and now works as a still photographer, do you know what it's like to not one but two careers in legacy media that are disappearing commercially?

August 2020

The “Social Distancing Diary” series continues with a look back at August 2020. Instead of the usual chronological approach, I am leading with an event that took place five years ago today — The Commitment March in Washington, D.C.

Speaking of disappearing careers, how does artificial intelligence affect photography? It's getting really, really realistic. Sometimes it's very difficult to even tell the difference. Five years from now, you won’t be able to.

AI can render me extinct from a business standpoint. You've got the tools. You can do it. But to me, it's sort of like eating a meal that has empty calories. What's the creative part of AI? The joy of this is not necessarily producing art in any way, shape or form. It’s the creation of the art; that’s what drives me at all times.

It’s like that thing you mentioned earlier with the dancers. They're technically correct, but maybe they're missing the emotion or the passion. Do you think people can sense that in your writing and photography?

I think they can. What’s interesting about this world we live in currently is that social media has made us, quote unquote, more “connected” than ever. And yet, I can argue that social media is what has made us so bad at communicating.

Why do you think vinyl records have come back? It’s because there's this desire to slow the heck down and have a tactile experience. The advantage of digital is that I can access anything that I want or need immediately with a search, but there’s so much out there that we don’t take the time to enjoy and absorb it.

I’ve resisted e-books for that reason. If I’m going to read a book, I want to read a physical book. I don’t want to do something digital all the time. I understand certain people do, and I respect that, but that’s just not me.

Questions from the Audience

Was this the first time you opened yourself up to this many editors? What was that experience?

It wasn’t death by committee. We're really great in the D.C. area at killing things by committee. … It was death by honest feedback.

I had 18 different people who looked at this and helped me winnow this down. And they were great. I honestly believe that more feedback is better whenever you can get it, because if you can get people who will be honest with you, who will look at your stuff and will give you an opinion, you have to take that opinion and absorb it, whether you disagree with it vehemently or not. You at least have to look at it and say, “This is affecting somebody this way.”

I sent them 400 photographs and said, “If you like it, give it a vote. If you don't like it, don't give it a vote.” The ones that had the majority of the votes cut it down to 120. At that point, I had to start looking at it from production and cost purposes, and I cut it down to 70. That was brutal. But they helped me get it down to that point, which I’m eternally grateful for.

Was there a particular moment that you decided, “I have a book on my hands”? What is the story of that moment?

I always knew I had something. After a year of walking around, you start to see sort of a narrative unfold. And while there's the day-to-day reporting that was being done, I had seen nothing that took a step back and tried to encapsulate a year.

My father was a history teacher, so I thought about what he would say: “This was an unprecedented time in our history.” We need to have some documentation of that fact.

What adjectives would you use to describe that year?

The first that comes to mind is obviously isolation. We were all very isolated during that time. The second that comes to mind is family, because we were fortunate to have our family for a lot of the time. The third was just weird. It was just so damn weird.

The other one that I would use is reflective. For anyone who's a Bloom County fan, Binkley's Closet of Anxieties opened during COVID and was sitting in your living room. Because we had so much time on our hands, every anxiety and everything that made you reflect on your past mistakes was there and out in force.

At the same time, it was an opportunity for growth. If you didn't take advantage of that opportunity, you'd be missing out. I had much greater depth in terms of my relationships with my children, with my wife, with people who are significant to me. I was very, very fortunate to be able to have that as a result of COVID, which was a bastardization of everything we ever faced in life.

Stuck in Time

One thing my late father and I shared, along with music and movies, was a fascination with time. How it bends, accommodates, frustrates. The pressure and adrenaline rush that time, or lack of it, brings during life’s most unexpected or unanticipated moments.

What would you do differently?

Well, my chiropractor would tell you that walking almost 4,000 miles in a year was a bad idea. And I should have probably figured out a way to do Door Dash because I could have brought some income into the house.

But looking back on it now, in hindsight, there were things I was initially defensive with my family members about as different events took place because I didn’t know or understand their circumstances, and I was dealing with my own stuff.

I was laid off in 2013 and had built a freelance business that was at its peak in 2019, and it just got consumed by the pandemic. When you lose 80% percent of a business that you worked seven years to build, I was just not able to get out of the weirdness of that loop for a while.

I should have realized I could pivot, to use a word, and figure out how to do something differently. But I couldn’t. I was stuck in stasis for a long time. Part of the chronicling, the 4,000 miles of walking — that, of course, became this book, which is great — also created a lot of shit for my family because I couldn’t move. I didn’t know how to move other than to walk.

So I am very blessed to have a spouse who is very patient, very kind, very loving, and forgave me for it anyway.

I have a limited number of copies of the hardback edition of Keep Your Distance: Walking Through the First Year of COVID. They are available for $40 plus $5.95 for shipping and handling. To order, visit this link. A smaller paperback version of the book also is available to purchase via Amazon. The price is $19.99.